A coming of age story—in a dystopian afterlife

Book review: Canadian author Neil Smith’s debut, ‘Boo’, posits a creepy, off-kilter reality for the youthful dead

no credit

Share

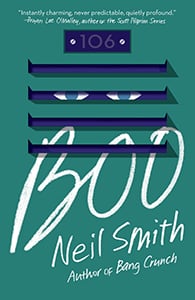

Boo

Neil Smith

In many a contemporary Bildungsroman, the hero comes of age by facing danger, sometimes life-threatening. In the dystopian world of Boo, the much-anticipated debut novel from Canadian writer Neil Smith, the quest is to unravel the past, not save the future; the hero is dead, and his afterlife—a terrifying thought—an only slightly off-kilter version of life before.

Oliver Dalrymple, 13, a.k.a. Boo, meets an early end in 1979, while standing in front of his locker and trying to recall all the elements of the periodic table. The next moment, he wakes up in a decidedly Earth-like hereafter that is entirely populated with Americans who died at the age of 13. Boo accepts his fate calmly. Death wasn’t entirely unexpected; he suffered from an inoperable heart defect. At least that’s what he believes finished him off, until a witness to his demise arrives and tells a completely different story.

Despite all the adolescents, this peculiar afterlife isn’t hell. In life, Oliver was a sickly, ghostly pale (hence the nickname), geeky only child of intellectual parents. He learns to fit in all over again in celestial middle school, this time with considerably more success. Perhaps it’s because this afterworld, known as Town, is full of literal old souls. Its populace of 13-year-olds stays that way for 50 years—never growing, but finishing out a normal lifespan—and then dies once again.

Town is like any other town. It has a museum, an asylum and a community centre that hosts Halloween dances (trends are slow to arrive with newly deceased imports; disco is just starting to catch on). It’s heaven, in fact, only heaven is rather boring. Townies do believe in God, except he’s called “Zig” and is more eccentric-uncle type than infallible deity.

Boo’s story isn’t really about death. After all, he can’t remember that. It’s about the burden of memory: why we recall seemingly banal things with agonizing clarity but not birth, or significant moments in our lives, in the same way. Smith suggests this phenomenon is not a function of unstable neural pathways, but of God’s (er, Zig’s) mercy. We mortals can’t process all the trauma and glorious hugeness of life. To function, we must, in part, forget. Boo makes his first true friend after his death, but they forge a bond while oblivious to the earthly events that brought them together. It has to be that way.

Boo does not take place in a coherent universe or posit a particular theology. The characters know nothing of who Zig is (if he even is), or why he’s inclined to toy with people so much. In short, this world makes no sense. In that way, it’s rather like ours.

GENNA BUCK