The book that gave us Shakespeare as we know him

Emma Smith’s close reading of Shakespeare’s first folio reveals a trove of information

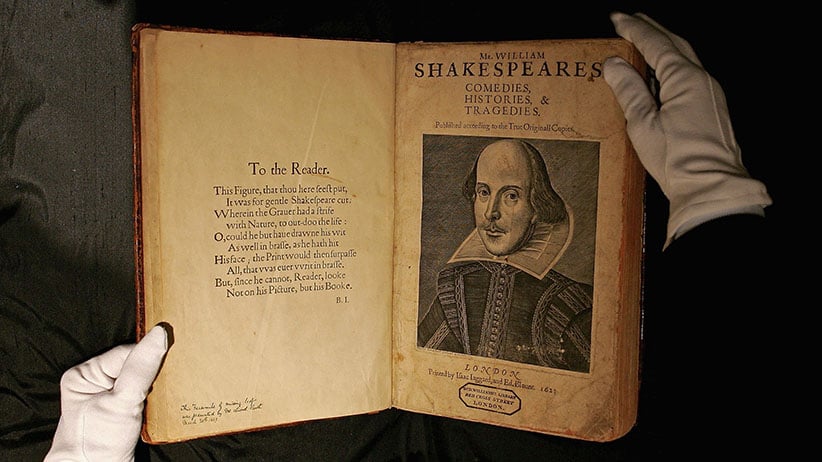

A Sotheby’s employee handles a copy of William Shakespeare, The First Folio 1623 on July 7, 2006 in London, England. The most important book in English Literature, the First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays (1623), will be offered in Sotheby’s sale of English Literature & History on July 13th, and is estimated to fetch GBP 2.5-3.5 million. (Scott Barbour/Getty Images)

Share

THE MAKING OF SHAKESPEARE’S FIRST FOLIO

By Emma Smith

In November 1623, at his bookshop at the sign of the Black Bear near St. Paul’s Church in London, Edward Blount took delivery of one of the most significant texts in world literature. Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, as it was then known, survives in 240 more-or-less intact copies, which sell (when available) for north of $6 million, while every public institution in possession of one treats it as a sacred relic. Its most obvious value lies in its contents: there are 36 plays included, fully half of which were making their first appearance in print. Without the First Folio, it is quite possible we would know nothing of Macbeth, Julius Caesar or The Tempest.

But Smith’s close reading of the folio reveals a trove of other information. There are the signs of a playwright who is also a working director and a canny businessman. One stage direction for Titus Andronicus may represent an author setting the stage while away from the playhouse and unable to take a good guess at how many players he can fit on it—or one cautious about his casting budget: Shakespeare wants a coffin, 14 named characters and still more actors, “as many as can be.”

Caution, in fact, was a byword for Shakespeare. In a text of The Merchant of Venice printed in the last years of Elizabeth I, Portia makes a dismissive remark about a Scottish suitor. That’s a line probably expunged in 1603 when James I, a Scottish monarch rather touchy about ethnic slurs, succeeded to the throne; if not, it was surely gone by 1605, after fellow playwright Ben Johnson was briefly imprisoned, in Johnson’s own words, for “writing something against the Scots.” In any event, Portia’s scornful words are not in the folio version, printed while James still ruled.

Nothing so becomes Smith’s beguiling volume, though, as its ending, where she looks at what margin notes in the surviving folios might say about Shakespeare’s reception among readers. One copy probably belonged to Lucius Cary, a nobleman known to have enjoyed both watching and reading plays. Cary loved The Tempest, and for more than one reason. He copied out Prospero’s speech on how “we are such stuff as dreams are made on,” which would appear to this day on virtually any list of great Shakespearean quotations, but he also seemed to enjoy a good insult (“thou debauch’d fish”) and the sailors’ off-colour ditty about Kate: “who loved not the savour of tar nor pitch / Yet a tailor might scratch her where’er she did itch.”

Cary and other early readers give us our first glimpse of what Smith calls “the reception” that would eventually lift Shakespeare to the highest rank in all English literature. The First Folio initiated the process through which most people have encountered Shakespeare’s words: by reading rather than hearing. Cary, like so many after him, seemed to find his own preoccupations mirrored; he appreciated the plays as entertainment and as intellectual argument; as sources of quotable poetry, psychological truth and bawdy humour. From one perspective, Cary is startlingly modern; from another, it’s Shakespeare, not him, who is our contemporary: the range and immediacy of the bard’s appeal have never wavered since Edward Blount set out his wares in St. Paul’s Churchyard.