An inside view of the Hermit Kingdom

Book review: Seven Names: A North Korean Defector’s Story

Share

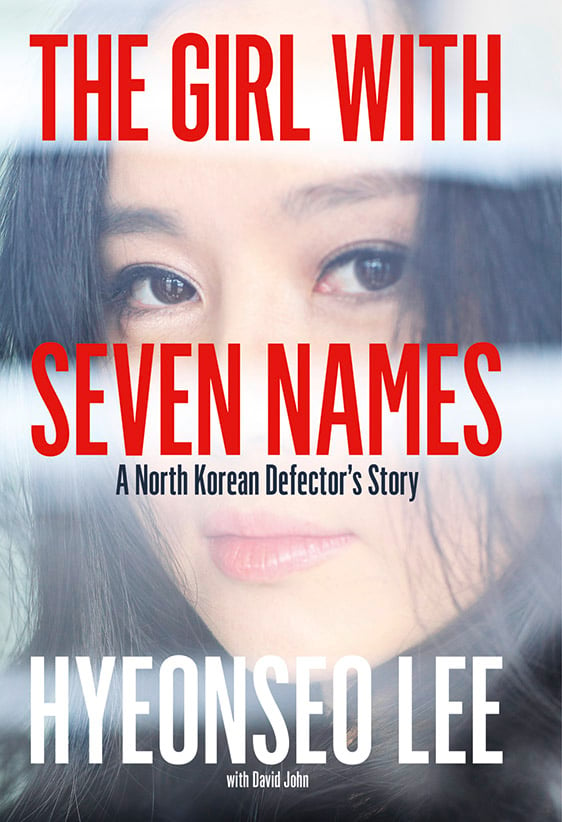

THE GIRL WITH SEVEN NAMES

Hyeonseo Lee

Under North Korea’s drab, totalitarian regime, daily life is a disturbing blend of banality and terror. In her memoir, Hyeonseo Lee, a high-profile defector who’s emerged as an activist and vocal critic of the regime, recalls how she tried as a young girl to avoid her town’s frequent public executions—attendance was mandatory from elementary school onward—but made an exception for a well-liked local smuggler she knew. “You might think the execution of an acquaintance is the last thing you’d want to see,” she writes; instead, most North Koreans tended to view the gruesome firing squads and hangings more like funerals—unpleasant, but unavoidable. “When the shot hit the popular guy’s head, it exploded, leaving a fine, pink mist,” Hyeonseo recalls vividly. “His family had been forced to watch from the front row.”

It’s just one example of how brutal regimes beget dysfunctional nations. Another: the man wasn’t being punished for trading illicit goods across the border, a relatively ubiquitous occupation in the border town of Hyesan that also employed Hyeonseo’s mother. He was executed because he was doing business when the country was supposed to be mourning the 1994 death of “Great Leader” Kim Il Sung. In other words, it was more dangerous to be seen as disrespectful to the regime than to be caught breaking its laws.

Hyeonseo recalls her indoctrination beginning almost at birth. In school, she was taught that North Korea was the greatest, most well-endowed country in the world and she shouldn’t hesitate to rat out friends or family for not being good communists. As she grew older, however, Hyeonseo began to spot glaring inconsistencies, including a friend’s mother who was boiling corn stalks for dinner despite the country’s vaunted food distribution system. (Thanks to her mom’s illicit activities, Hyeonseo and her brother always had food on the table.) To further broaden her horizons, she decided to slip across the river into China before turning 18, after which she could be punished more severely. She quickly discovered her supposedly superior country was hopelessly backward, and that she didn’t want to go back—nor could she, as her family was forced to say she had gone missing to avoid falling under suspicion themselves.

The long road that finally led Hyeonseo and, eventually, her mother and brother, to South Korean citizenship more than a decade later was littered with sketchy brokers, corrupt officials and numerous close calls—all of which Hyeonseo managed to avoid thanks to steely nerves and what must be one of the world’s best poker faces. As for adjusting to their new lives and freedoms, it’s very much still a work in progress.