Book review: Michael Faber’s strange new novel

In what he has said will be his last novel, Faber has constructed a story that brims with suspense

Share

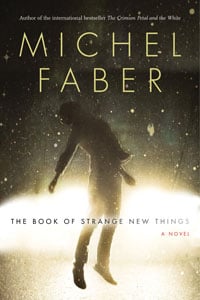

The Book of Strange New Things

Michael Faber

If Earth moves past the point of no return, there are surely worse planets to which humans could retreat than Oasis, the locale of Faber’s new novel. The water is clean, the atmosphere agreeable and the natives benign. More than benign, in Peter Leigh’s case. The newly arrived British pastor has been hand-picked by a mysterious corporation called USIC to provide religious leadership to the indigenous Oasens and is naturally apprehensive about how he will be received by them. He is also desperately lonely for his wife, Bea, who was rejected for the journey by the fastidiously discerning USIC. But, in his first encounter with the Oasens, Peter is eagerly, almost impatiently, welcomed. The Oasens already know about Jesus—in fact, they identify themselves to Peter as Jesus Lover One, Two, Five, Fifty-Four and so on—and are hungry for teachings from the Bible, a name they are loath to utter, so sacred is it to them. Instead, they refer to it as the Book of Strange New Things.

Peter moves into the Oasens’ settlement for weeks at a time, returning to the USIC base to shower and correspond with Bea via the “Shoot,” a kind of interstellar email system. He becomes enthralled with his new “flock,” who, despite being somewhat unappealing to him visually—their heads resemble “a placenta with two fetuses” consisting of “a tangle of translucent flesh that might contain . . . a mouth, nose, eyes”—are, in many ways, ideal Christians: modest, humble and lacking in ego. Peter feels less connected to the humans employed by USIC, a decidedly bland bunch with little interest in anything outside of their jobs. But he experiences an even bigger emotional gulf in his relationship with Bea, finding himself strangely unmoved by her increasingly dire accounts of disaster back home: freak weather wiping out whole cities and countries and, more locally, food shortages, power outages and rampant hooliganism. Peter struggles to know how to comfort Bea from such a distance; sometimes he struggles even to respond.

In what he has said will be his last novel, Faber has constructed a story that brims with suspense. Things seem almost too perfect between the Oasens and Peter; you can’t help but wonder if, and when, they might turn on him. USIC, too, is shrouded in mystery: Do they have intel that Earth is about to implode? Underneath all this narrative excitement, a much more subtle and meaningful tension is at play: the question of whether we can truly fix what we’ve broken—our own spirits, our most important relationships, the planet we live on.