Five must-read books for October

Jennifer Egan delves into historical narrative; Kevin Hardcastle tells a foreboding tale of attempted redemption; and John DeMont takes on the history of his home province

Woman place her arms on her lap and open book to read

Share

This month in books: John DeMont returns to his Nova Scotia roots; Garry Willis writes about the Qur’an after a lifetime studying Christianity; Jennifer Egan defies expectations again with an expansive historical novel; and Edward St. Aubyn puts a novel twist on the Shakespeare classic of King Lear. See all of our book reviews.

WHAT THE QUR’AN MEANT AND WHY IT MATTERS

Garry Wills

This is an oddly humble book, not least because of the eminence of the author, and all the better for it. Wills is a Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian and one of his country’s leading Roman Catholic intellectuals. Yet before 9/11, Wills admits with open embarrassment, he had never read the Qur’an: “I had spent my whole adult life studying Christianity, while remaining ignorant of the only other religion of a similar scale.” Although the 83-year-old scholar has been making up for lost time since, Wills still brings a sense of wide-eyed wonder and thoughtful, hesitant probing to Islam’s sacred text.

He also brings a deep historical awareness of parallel paths in Christianity. Supporters of every development in his own faith, from the Crusades, the Inquisition and sexual prohibitions to hospitals and aid work, Wills argues, root those concepts in scripture, but none of them are actually found in the Gospels.

Likewise Islam and the Qur’an: where, asks Wills, are the strictures of sharia law; where is the command to kill infidels; where, indeed, are the 72 virgins set to greet “the murderers of 9/11?” Pretty much in the same place, the historian suggests, where the Christian decisions to wage holy war and to burn dissidents alive can be found: in the minds of zealots with political power and economic interests to defend.

What Wills does find in the Qur’an are aspects that make a Catholic of his generation “feel at home”—the honour ascribed to the Virgin Mary, the only woman named in the text; the beliefs proclaimed, as in the Catholic catechism, in angels and devils, heaven and hell, the Last Judgment. Other themes he finds strange but appealing, especially the Qur’an’s ecological consciousness. Like the Bible, it is a desert book, but for Wills one more suffused with the interconnectedness of creation and the sacredness of water, which is the essence even of hell, where it is poured boiling down the throats of sinners.

For Wills, the Qur’an is a foundational text as protean as his own faith’s scriptures, as full of spiritual nourishment and possibilities for good and ill. And that is the reason why what the Qur’an meant matters.

—Brian Bethune

THE LONG WAY HOME: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF NOVA SCOTIA

John DeMont

Line up Canada’s 10 provinces and three territories and ask the classic test question, ‘Which of these is not like the others?’ The inhabitants of each—not just the Québécois—will cry out, “Us, us, us.” And they’ll all have a strong case to make, just as John DeMont does in his very personal history of his home and native patch.

Every wave of settlement on this disparate half-continent since the glaciers began to recede has been whipsawed by climate and history and our defining stories have always been about loss and survival. And every part of the nation feels itself distinct, pushed around and, as DeMont says of his fellow Nova Scotians, “a bit player in the big story.” It is the blandest of ironies to point out that that belief is, in fact, one of the great pan-Canadian unifiers.

Still, DeMont is not wrong about his province’s unique circumstances. In an account that’s as haunted as it is haunting, he spends considerable time among ruins, from 17th-century French forts to vanished Acadian settlements to abandoned coal mines, telling tales of vanished ways of life.

Nova Scotia has never quite worked out economically, DeMont notes, at least outside the flourishing city-state of Halifax. Elsewhere there is a centuries-old pattern: nothing much of anything, a few good years (coal mining, Age of Sail trade, even privateering), a rapid decline, nothing much of anything, repeat.

It’s the perfect backdrop for DeMont’s engrossing stories about people who keep banging their heads against brick walls. Chief among them is journalist and politician Joseph Howe, never far from the author’s thoughts. Howe is now counted—quite against his will, given his heartfelt anti-Confederation stance—among the greats of Canadian history for his successful battles for press freedom and responsible government.

But DeMont loves him for the tenacity of his dreams for Nova Scotia: the way Howe simply endured, like the Acadians, the Mi’kmaq, the African-Canadians and “the pasty-faced Celts like myself, who have also hung in, making the place what it is.” And what, exactly, is that? DeMont can no more put a finger on that than anyone else trying to articulate what makes his native land so special. But a reader can do it for him: it’s home.

—Brian Bethune

MANHATTAN BEACH

Jennifer Egan

Jennifer Egan’s career (including her 2011 Pulitzer Prize-winning A Visit From the Goon Squad) has been built, in part, on a thwarting of expectations. And now she has done so again, this time by writing a narratively conventional historical novel spanning the Depression to the late days of the Second World War. The emotional intelligence that underpins it is far from ordinary, however: Manhattan Beach ends up circumnavigating the globe, but its most impressive and expansive moments occur in the narrow wartime Brooklyn world that serves as its primary setting.

In its opening scene Anna Kerrigan, age 12, accompanies her father, Eddie, to the home of the charming mobster Dexter Styles for a mysterious meeting. Her vague memories of the pivotal day, which culminates in a frigid stroll along Manhattan Beach, will prove key when Anna re-encounters Dexter Styles five years after Eddie, a “bagman” for Irish union bosses, suddenly goes missing.

As the novel unfurls in its leisurely but riveting, real-time way, we’re forced to speculate: Was Eddie killed? Did he flee? Or was the burden of caring for Anna’s mute, severely crippled sister, Lydia, simply much too onerous?

As troops ship overseas in increasing numbers, Anna finds respite from long days spent helping her ex-chorus-girl mother care for Lydia in their cramped walkup, through the war-related work now being offered to women. A tedious but critical job measuring ship parts in the Naval Yard proves unfulfilling, so she seizes on the improbable notion of becoming a Navy diver and—through a combination of curiosity, persistence and dumb luck—eventually achieves her goal.

The novel’s first three-quarters are vivid and consuming. That said, Egan isn’t immune to the pitfalls of sharing the fruits of her copious research: the book feels overly informative in places. More problematically, its later parts suffer from an uncharacteristic reliance on coincidence and circle-closing as plot devices.

Egan follows a fine American tradition of using the sea as a symbol for transformation, but though an extended episode about the torpedoing of a merchant marine ship convinces in its details, its outcome is strained, credulity-wise.

Top-notch writing and meaty characters are Manhattan Beach’s saving grace. Anna is an outwardly good girl with an inner rebellious streak, and as small a thing as our anticipation of how, and when, her true nature will reveal itself stands as one of its many indelible pleasures.

—Emily Donaldson

DUNBAR

Edward St. Aubyn

The Hogarth Shakespeare project, for which the Bard’s plays are “re-imagined” into novels by renowned authors, has been beyond sharp in its pairings so far. But none is as inspired as turning loose Edward St. Aubyn, chronicler of upper-class British depravity, on King Lear. St. Aubyn, 57, has written five novels about the Melroses, a fictionalized version of his own wealthy family, openly portraying how he was raped repeatedly by his father between the ages of five and eight, his ineffectual mother, his prodigious youthful drug abuse and suicide attempts. What makes the novels art is not the horrific origin story, though, but their meld of suffering and corrosive social comedy—nightmares filtered through an Evelyn Waugh lens. And whether it’s personal history or Shakespeare’s dramatic power that form the root of his literary obsession, critics have noted that St. Aubyn often references Lear in his work and conversation.

The novelist doesn’t disappoint in Dunbar, in either familial vivisection or the blackest comedy, the latter primarily involving its title character’s elder daughters, Abigail and Megan, more vicious and far funnier than Goneril and Regan. Henry Dunbar, an egomaniacal media mogul with a Scottish name and Canadian (read colonial) roots, brings to mind historical figures from Toronto-born Lord Thomson of Fleet to Australian Rupert Murdoch to a hint of Donald Trump, whose mother hailed from the Hebrides. While Peter Walker—a severely alcoholic comedian jugged up in the same high-end sanatorium as Dunbar—is not as wise a fool as Shakespeare’s, he is just as antic: “Decadence, decay and death,” he chants, “how lightly we have tripped down those stairs, like Fred Astaires, twirling a scythe instead of a cane!”

After days of secretly spitting out their meds, Dunbar and Walker escape into England’s rugged Lake District, the latter in pursuit of booze, the former in an attempt to recapture his crown—that is, control of his corporate empire—and reconcile with his youngest daughter, Florence, the only one who actually loves him. Throughout Dunbar’s struggle on the stormy heath, interspersed with brilliant skewering of privilege, a reader can see both the tragedy of Shakespeare’s old man—who “but ever slenderly knew himself”—and hints of the journey to self-awareness that must once have saved a much younger St. Aubyn.

—Brian Bethune

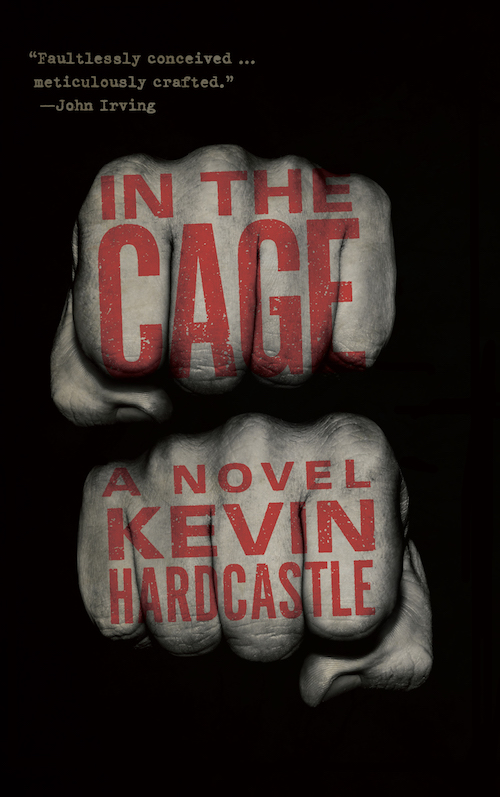

IN THE CAGE

Kevin Hardcastle

Interviewed back in 2015, before his debut story collection, Debris, won Trillium and ReLit prizes, Kevin Hardcastle described his relationship with Simcoe Country, his former stomping grounds, as “contentious.” Aside from the “wondrous [home]town of Midland,” there are, he said, “other embattled, isolated rural towns and villages” that surround it. In the Cage, Hardcastle’s disheartening but engrossing debut novel, could easily be recounting a tragic conflict unleashed in one of these embattled towns.

The author sets this notably stylized (and arguably pessimistic) story of attempted redemption in a foreboding environment where weather is bleak, roads are grim, trees and faces are gaunt, and jobs few and far between. Hardcastle’s singular portrayal of imperilled subsistence just two hours north of Toronto provides less a love letter to home than a testimony of its corroded soul.

In plain-spoken, Hemingwayesque sentences, the story begins with an overview of protagonist Daniel’s feral, continent-wide, mixed martial arts bouts in backwoods cages and rings “stained and stained again with men’s blood.” One fight in Alberta results in an eye injury that forces him into early retirement. A man of few words and little revealed interiority, Daniel returns to Simcoe County with his wife and daughter. Possessing scars on “hands broke and rebroke” and a much-pummelled face along with a well of brute strength, he winds up working as hired muscle for a local gangster after someone steals the welding rig off his truck. Free once he completes a last job—or so he’s told—Daniel returns to welding. When the shifts dry up, he finds a gym, eager to fight again and hopeful that a win inside the ring will provide financial security.

Hardcastle also pays close attention to the increasing viciousness of Daniel’s former “hillbilly thug” boss and his brutal lieutenants. While the stories run parallel for a time, it’s clear that Hardcastle knows genre characteristics and is working within them. The grisly convergence of the two oppositional forces is all but inevitable. The fainthearted should be wary of the resulting blood spatter.

Absorbing yet harrowing, and possessed of an outlook that recalls Hobbes’ state of nature (and the “nasty, brutish, and short” life therein), the darkness of In the Cage commands attention even as it prompts revulsion.

—Brett Josef Grubisic

MORE BOOK REVIEWS:

- The five books everyone is talking about in September

- The five books everyone is talking about this August

- Must-read books for June: Play to prose, restaurant reflections

- Rogers Writers’ Trust shortlist shows off accelerating diversity of CanLit

- The 2017 Giller prize longlist: Twelve books that caught our fancy

- Adam Gopnik’s memoir is part love story set in 1980s New York

- How Daniel Mendelsohn found his father through Homer’s ‘Odyssey’

- Salman Rushdie says Donald Trump is “demolishing reality”