George Elliott Clarke takes risks in his new novel

A new novel from Canada’s parliamentary poet laureate attempts to mesh the oral and the written, with mixed results

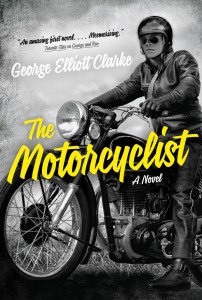

Young Bill. (Clarke Family)

Share

THE MOTORCYCLIST

By George Elliott Clarke

Since the end of slavery, black North Americans have defined freedom as the right to go where they want and love whom they want. The African-Canadian hero at the centre of Clarke’s second novel holds those truths to be self-evident. Carl Black, 23, cuts a dazzling figure, cruising along Halifax’s streets on his BMW motorcycle. Carl checks linens for CN Rail. But he fancies himself a beatnik in the tradition of Kerouac, his magnificent bike and love of art setting him apart from ordinary black men. Carl is a non-stop philanderer who seeks true love. The desire of his heart is for a white woman. It’s a dangerous wish in 1959 Nova Scotia, but Carl sets out “to seduce as many (milk-white) ladies as he may.”

Clarke, Canada’s new parliamentary poet laureate, loosely based his story on a year in the life of his late father. Mid-20th-century Halifax is the Deep South in the Great White North, where wealthy, white families reside in stately South End homes served by black domestics who return nightly to the violent, poverty-stricken North End. Here Carl grows up one of five illegitimate sons born to an exhausted laundress. “Coloured women are for work,” Carl surmises, “White women are the most desirable.”

His mother, Victoria, has sunk beneath her station. The family lives in a rat-infested barn in her father’s backyard. He is a distinguished pastor who favours her famous sister, even though Pretty bore a child out of wedlock. Clarke offers this scathing exposé of his forebears, the Whites, long considered to be “coloured” Nova Scotia’s first family. His great- grandfather, Rev. Andrew White, was the only black chaplain to serve British Forces in the First World War. His great “Aunt Pretty” is the renowned contralto Portia White.

Carl happily sets off on a road trip that will take him away for a time from this harsh community descended from black loyalists and Canadian slaves. In contrast, characters in the black novels of central Canada head south to find—not flee—black community.

Clarke takes a number of risks with this book. He has attempted to mesh the oral and the written, and we are deluged by words—adverbs, adjectives, metaphors, witticisms, allusions. Naturally it is easier to find one or two apt adjectives than it is to find eight, and Clarke frequently obscures the image or emotion he hopes to convey. It’s a problem. And there is no guarantee black readers will tolerate a hero who embraces the historically racist stereotype of superior white womanhood. However, this strange riveting novel of an Africadian and his times is worth the effort.