Gilding the lilies: Ross King wins the 2017 RBC Taylor Prize

King’s fourth nomination served up a win that studies of a much younger Monet, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci did not

Water Lilies, 1916 by Claude Monet. Found in the collection of the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo. (Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Share

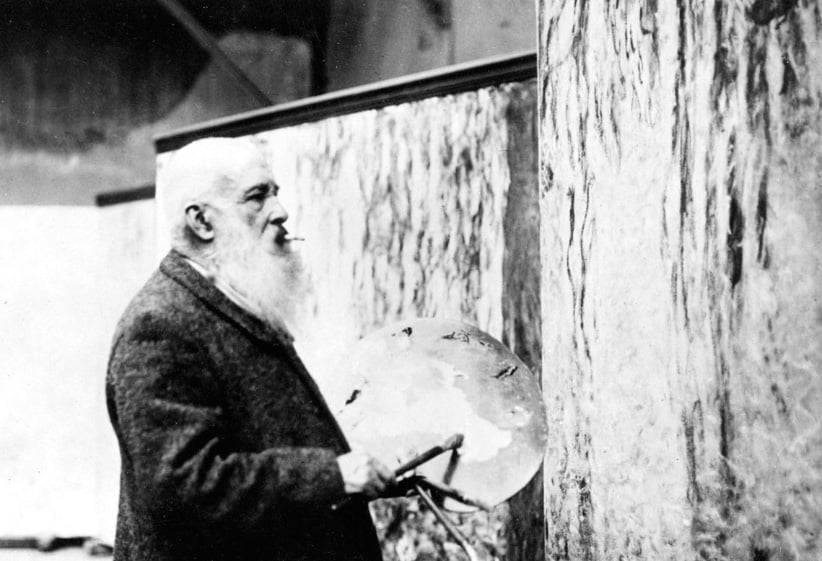

Fourth time lucky, despite sitting at Table 13, Ross King won the $25,000 RBC Taylor Prize for literary non-fiction on March 6. Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies saw King through after previous nominations—for studies of a much younger Monet, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci—did not. The other four nominees featured, along with King’s book, in a nice summary by juror Colin McAdam. His next novel, McAdam deadpanned, would be about a woman having an affair with a convict (Dianne Schoemperlen’s This Is Not My Life); she was also an Israeli soldier (Pumpkinflowers by Matti Fiedman), who had lost her family in the Holocaust (By Chance Alone, Max Eisen). And she’s the inventor of a strange new device “that I call the wireless” (Marc Raboy’s Marconi), which she uses to talk to her friend, who paints water lilies for a living.

MORE: Watch interviews with this year’s Taylor Prize nominees

In King’s highly popular explorations of crucial moments in art history, the ones he wants “to unpick, maybe reverse-engineer, whether it’s Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel or Leonardo in Milan, to see how the process unfolded,” late Monet brought King closer to the present day than ever before. Some researchers of the more remote past can be overwhelmed by the amount of evidence still kicking around from a time barely outside living memory. King, though, reveled in it. “I loved it—the more stuff, the better. I felt I could get to know Monet better than anyone else I’ve studied, especially since Michelangelo and Leonardo were notably reclusive characters.” And in the end, it didn’t matter. King may have had more data on, say, Monet’s paint supply purchases than anyone could hope to have for a Renaissance artist, but the his subjects had similar dilemmas and their stories were similarly opaque: “It’s never clear until the very end whether they’ll even finish the job, let alone produce masterpieces.”