Grace Jones writes her memoir

A majestic and defiant book from the singer, actress and model

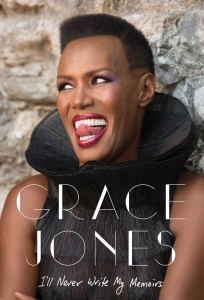

I’ll Never Write My Memoirs. (no credit)

Share

I’LL NEVER WRITE MY MEMOIRS

Grace Jones

Somewhere between Maria Callas and Genghis Khan sits the literary voice of Grace Jones. Her writing is like her singing—growling, ferocious and sharp. It’s not the diva prose of a Diana Ross or Aretha Franklin—paragraphs masticated by worried publishers, shaky lawyers or co-writers hired to strangle the intensity of the truth. Jones’s storytelling is majestic and defiant. The singer, actress and former model does not waste any time clouding her past. In fact, her approach to spilling the tea on her life reflects her father’s fierce Pentecostal sermons. (Her father is Jamaica’s famous pastor, Robert W. Jones.) She has a way with words that is as powerful as his and, by the second chapter, the reader is convinced the Jamaican-born, New York-raised wild child was destined to address a congregation of her own.

Jones’s fans, of course, are not the deeply religious audiences she grew up with in Spanish Town. (She writes that she felt “abused and oppressed” by her hometown church.) After fame hit in 1975 with the hypersexual hit I Need a Man, Jones quickly found out her crowd was also not made up of Billboard-worshippers. Record-company types tried to limit her. Obviously, they failed. Jones had a period of mainstream success, with a few chart hits such as Slave to the Rhythm and Pull Up to the Bumper, which she reveals, contrary to reports, is not about anal sex. (“If you think the song is not about parking a car,” she writes, “shame on you.”) In the mid-’80s, Jones also went on to enjoy a moment of blockbuster appeal. (She starred in A View to a Kill and Conan the Destroyer, during the shooting of which co-star Arnold Schwarzenegger was quoted as saying he was “perpetually scared by her.”)

Through it all, Jones’s feet were firmly planted in the underground. It was the clandestine gay clubs of France and Italy, and New York’s bygone art world, that inspired her most. There are her tales of being “a fuse, not a muse” for artists such as Andy Warhol, Helmut Newton, Keith Haring (who, famously, painted her body for various performances and for the cult film Vamp) and illustrator and former Esquire art director Jean-Paul Goude (with whom she is angry for recreating her Island Life album art with Kim Kardashian for a Paper magazine cover last year).

Many of her most audacious days (pre- and post-Studio 54) get the ink they deserve in this memoir. Jones reminds readers that she’s not only an expert eyewitness to the height of ’70s, ’80s and ’90s hedonism, but a wholehearted participant. But this is a record of more than Jones’s outsized life and work. Since disco, house and electronic dance music rarely get historical documentation, Jones’s book can be counted as a serious interpretation of the art and artifice of three significant decades in clubland. Over 10 albums, she ushered in new sounds and looks, working with collaborators such as Tom Moulton (named the father of disco), and Trevor Horn (Art of Noise, Frankie Goes to Hollywood).

Jones, unlike many, lived to see the effects of it all—the debauchery, but also the change in a society that was transforming from the underground up. Her observations on encountering racism, misogyny and the early days of the AIDS pandemic are as poignant as her stormy persona. But she is, at heart, an artist, and she reveals here her creative process as she revisited and remade various dance-music genres, creating a soundtrack to what was a burgeoning LGBTQ civil rights movement.

Forty years later, Jones remains a radical. In one particularly spicy chapter, she addresses what keeps her far away from what she deems is the mediocrity of Rihanna and Lady Gaga—pop stars she says continue to mimic her past and present work (there are detailed examples in the book) and “play the pioneer without taking the actual risk.” No one can accuse Grace Jones of that.