In the world of Canadian book prizes, fiction meets politics

Increasingly, Canadian writers are finding creative fire in issues, identity and the immigrant experience

Share

“This year, I had the luck.” No literary award winner has more succinctly summed up the opaque process of becoming the writer who emerges with cheque in hand than Yann Martel after taking the Man Booker Prize for The Life of Pi in 2002. But if the human drive to establish patterns hits a wall when it comes to discerning larger meaning in a victorious book, it can find a path forward in the lists of nominees. Prize short lists, the five or six authors vying for an award, and, even better, the new long lists (more data!), are indicative of more than just jurors’ tastes—what is out there to choose among, for one—and sometimes also predictive.

READ: Scotiabank Giller Prize short list carries plenty of experience

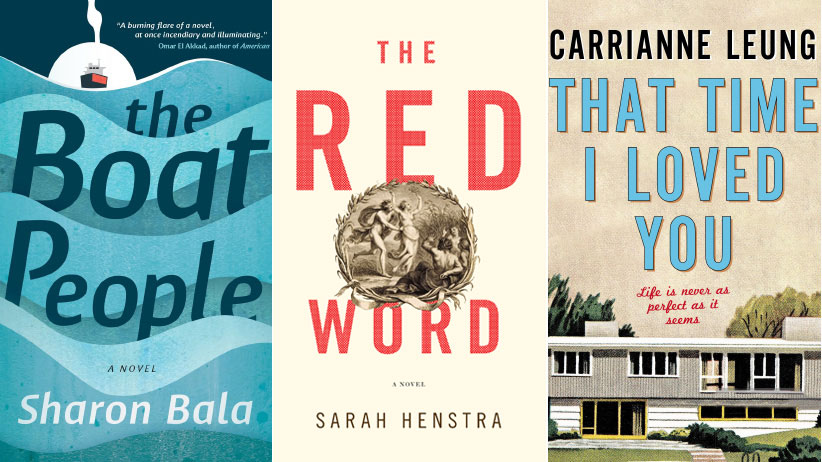

The coming year will be a time to test that notion in Canadian literature, given the way 2017’s national prize juries have shown, in a politically roiled era, unusually clear responses to politically charged writing. When more of the same land in bookstores in 2018—among them, Sarah Henstra’s novel The Red Word, which explores rape culture and sexual harassment on campus; That Time I Loved You, a novel by Carrianne Leung set in a 1970s Toronto suburb full of immigrants; and The Boat People, 2017 Journey Prize winner Sharon Bala’s debut novel about a group of refugees who arrive in Canada by ship only to be greeted by fear and suspicion—how will readers and fellow authors respond?

In September, the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize—newly enriched to $50,000 by the communications company, which owns Maclean’s—was first out of the gate among Canada’s three major literary awards with its short list. Finding a pattern wasn’t difficult. Jurors Michael Christie, Christy Ann Conlin and Tracey Lindberg—all writers—presented a list where larger social themes were never far from the surface.

READ: Rogers Writers’ Trust shortlist shows off accelerating diversity of CanLit

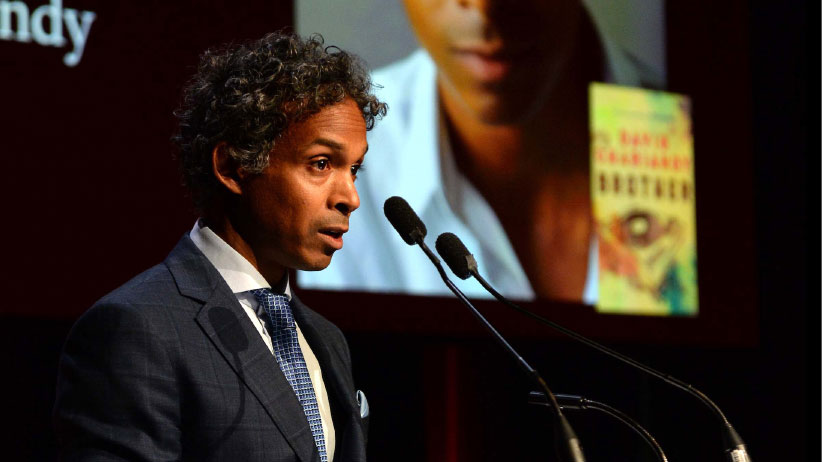

The winner, announced on Nov. 14, was Brother by David Chariandy, the son of Trinidadian immigrants who grew up in an inner Toronto suburb. It’s a novel that undeniably hit a sweet spot: a beautiful piece of literature that also pushes an urgent social issue into mainstream awareness in the intimate, intuitive, connective way only fiction can. “Chariandy’s book blew us away,” says juror Christie. “It just completely spoke to us: the writing, the subject matter, the humanity of the story, the necessity of telling a story set in Scarborough in an immigrant community and bringing up issues like toxic masculinity and gun violence. Everything that came up in the book just felt so organic and convincing and moving to us.”

Much the same could also be said of the other nominees: Carleigh Baker’s book of short stories, Bad Endings; the novel American War by Omar El Akkad; Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s genre-defying This Accident of Being Lost; and Claire Cameron’s novel The Last Neanderthal. “Literary merit” is in the eye of the beholder—in 2017, for the first time this century, there was no overlap between the WT, Scotiabank Giller and Governor General’s finalists—but there are no politically correct clunkers on the WT list. “Our mandate as jurors was to pick the books of highest literary merit, and that is exactly what we did,” Christie adds. “That being said, we selected books with the most vitality, the most heat and the greatest charge. If that makes them political, it was a by-product of our selection process.”

WATCH: David Chariandy on his prize-winning book “Brother”

It’s not coincidental that Victoria author Christie, born in Thunder Bay, Ont., an epicentre of the rapidly evolving relationship between Canada and Indigenous peoples, pays close attention to events in his hometown, a place he describes as “deeply racist in its DNA.” Or that fellow juror Tracey Lindberg is an Indigenous author and academic very aware of the importance of “being in the room”—that is, wielding the control jurors possess—when money and prestige are apportioned. As critic Nick Mount, author of Arrival: The Story of CanLit, notes, “Literary/arts awards have always been based on both aesthetic and political criteria. And they always will be, until we replace jurors with machines.” If jurors’ life experiences are significant, however—and how could they not be?—they are not determinative. It was the story of Black youth in Toronto, after all, that took the prize.

Not that the entire CanLit community is thinking the same way. A week after the WT list was announced came the short list for the Giller, the nation’s most lucrative ($100,000) and prestigious literary prize. Not only was it entirely different, there were hints it was consciously so. Juror André Alexis, who won both the Giller and the Rogers Writers’ Trust awards last year for his novel Fifteen Dogs, is an unusually outspoken member of a notoriously risk-averse national book trade. (The last time significant numbers of Canadian authors chose sides and stuck their heads above the parapet was a year ago, after the University of British Columbia fired Steven Galloway, the head of its prominent creative writing program, for never entirely explained reasons. The resulting war seems likely to send them all back to vows of perpetual silence when it comes to their peers. L’affaire Galloway has since faded into obscurity.)

Alexis, who spoke out calmly during another heated CanLit moment in May, when questions of cultural appropriation and minority representation in media and the literary world (briefly) dominated the media (social and otherwise), earlier this month took the rare step of critiquing another prize’s jury. The Writers’ Trust list, he told a reporter, was the work of a “kind of social-justice jury,” which “emphasized political content of the work, whereas the Giller Prize was emphasizing simply books that we thought were well-written and that we could defend on aesthetic terms.” The clue, continued Alexis, lay in the Writers’ Trust jury’s citation for Cameron’s The Last Neanderthal, which called it “feminist literature of the highest order.” The WT jurors “put the emphasis on the political aspect of the book, whereas we looked strictly at Claire Cameron’s writing” (before proceeding not to nominate it). As Mount’s common-sense observation points out, and the presence on the Giller list of Eden Robinson—whose exploration of the toll levied on Indigenous Canadians by residential schools is as much a part of her writing as her sly humour—demonstrates, Alexis’s claim is literally impossible.

But if he meant, as seems likely, that his jury felt ideological content detracts from, rather than empowers, writing, the Giller short list fits that concept. There’s Robinson: if writing by Indigenous authors as a whole is more embraced than ever by Canadians, the 49-year-old member of B.C.’s Haisla and Heiltsuk First Nations is having a moment of her own—a year ago she won the $25,000 Writers’ Trust prize for mid-career authors and last month the Trust awarded her a $50,000 WT Fellowship. The Giller jury gave her novel Son of a Trickster a nod for grounding its protagonist’s life in “gritty, grinding reality,” but stressed how Jared’s “addled perceptions take us into a realm beyond his small-town life, somewhere both seductive and dangerous”—that is, to a place more literary than political.

Trickster was joined by Transit from Rachel Cusk, a Saskatoon-born British writer both celebrated and criticized for her seeming indifference to political issues and fixation on family life; I Am a Truck by Michelle Winters; Toronto-born Irish writer Ed O’Loughlin’s Minds of Winter; and the winning title, Bellevue Square. Praised in the jury citation for its “complex literary wonders, the doppelgangers and bifurcated brains and alternate selves,” Michael Redhill’s exceptional novel also embodies another moment in CanLit, which is increasingly a geographical descriptive that embraces a host of identity-conscious and regional literature: the Toronto novel is coming into its own. And Redhill himself notes one of the underpinnings of Bellevue Square is the massive change his hometown has experienced in his lifetime.

When the world feels more unsettled than it usually does, and the future appears more daunting than hopeful, art will necessarily reflect that. Technological change, income inequality, relations between men and women, the interlinked issues of migration and climate change: all will be reflected in what Canadians (and others) write. And what they will celebrate. The Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize is the most sensitive to change of Canada’s three major literary awards, and its juries are more likely to be staffed by writers still early in their careers. It’s always been the most predictive in the sense that authors are more likely to win the WT and then go on to the Giller than the reverse. “I think Canadian literature is in a really exciting and fresh place right now,” remarks Christie. “I’ve never before read just about every single book published in Canada in a particular year. It was a snapshot of all we’re capable of doing—incredible breadth and diversity of voices and approaches. It’s open to more participation from different places on different issues and themes than it ever was.”

MORE ABOUT BOOKS:

- Joe Biden: Hope, unchanged

- ‘I am a living breathing lie’: Tom Wilson on learning the truth of his birth

- Why Granta dedicated an entire issue to Canadian writing

- “The Rememberer,” a short story by Johanna Skibsrud

- Here are six must-read books for November

- A question for author Claire Cameron: Are you a political writer?

- The poetry and wisdom of Joni Mitchell and Gordon Lightfoot