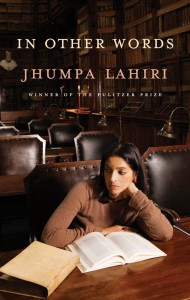

Jhumpa Lahiri renounces English for Italian

The Pulitzer-Prize winner writes a memoir about learning Italian

Share

By Jhumpa Lahiri

It’s tempting when approaching In Other Words, Lahiri’s first book in Italian— a language in which she began writing after living in Italy for only a year—to marvel at the temerity of the exercise. Oh for the prodigious talent to renounce as burdensome a language that won you a Pulitzer, and to begin anew in an alien tongue. But it’s clear early in Lahiri’s startlingly beautiful memoir of learning Italian—her “linguistic autobiography,” as she dubs it — that this is not some cerebral experiment but an almost sadistic project born of an incomprehensible and decades-long infatuation.

Lahiri studied Italian for nearly 20 years before deciding a few years ago to immerse herself, giving up reading or writing in English. She read Italian books obsessively, underlining new words, gathering them, she writes, as if she were going into the woods with a basket. She researched their meanings, made copious notes—and watched the words evaporate from her memory. In 2012, she uprooted her family from Brooklyn for a bewildering move to Rome, drawn not by the beauty of the city but by the architecture of the language—its rhythm, its logic. In Rome, her alienation from English was complete—even translating this book was too much for her. That job falls to Ann Goldstein; in the English edition, the original Italian text appears on the verso pages.

Over the course of the book, Lahiri puzzles over why she has done this, traded expertise for uncertainty, imperfection. Her Italian is much more primitive than her English. “It’s like writing with my left hand, my weak hand,” she says at one point — “a transgression, a rebellion, an act of stupidity.” She even apologizes for writing the book. But this vulnerable new voice, she discovers, is also her most honest. From this constraint–she lacks words, many words, those fundamental tools of a writer, and the intricacies of grammar elude her—is born a freedom, and a fearlessness.

In 1999, Lahiri seemed to appear fully formed. Her debut short-story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, won the Pulitzer. 2003’s The Namesake signalled a new Indian literary voice that narrated, in perfect, precise prose, the hyphenated American experience. In this unflinching memoir, we see a writer remaking herself, learning to write, as if for the first time. In place of the sharply observed details of those earlier books is abstraction, a deeply personal meditation as elegantly conveyed as anything Lahiri has written. Her book is about writing, and language itself, the medium through which a writer experiences everything.

As a speaker of Bengali and a scholar of Latin and ancient Greek, Lahiri did not come lightly to her infatuation. But her hunger for Italian — a self-imposed sentence of linguistic exile for a writer who had already lived in that state for years — is in part escape from an English-Bengali clash that has ruled her life, the inevitable Janus-faced fate of the immigrant. She invited this impoverishment, she says, because it offers something — “a stunning clarity, a sense of being alive.” For the reader, this book does no less.