Jordan Peterson’s upcoming book has opened up a clash of values at its publisher

Employees at Penguin Random House Canada speak out on how they’re rethinking their workplaces and why publishing, writ large, should weigh its moral responsibilities

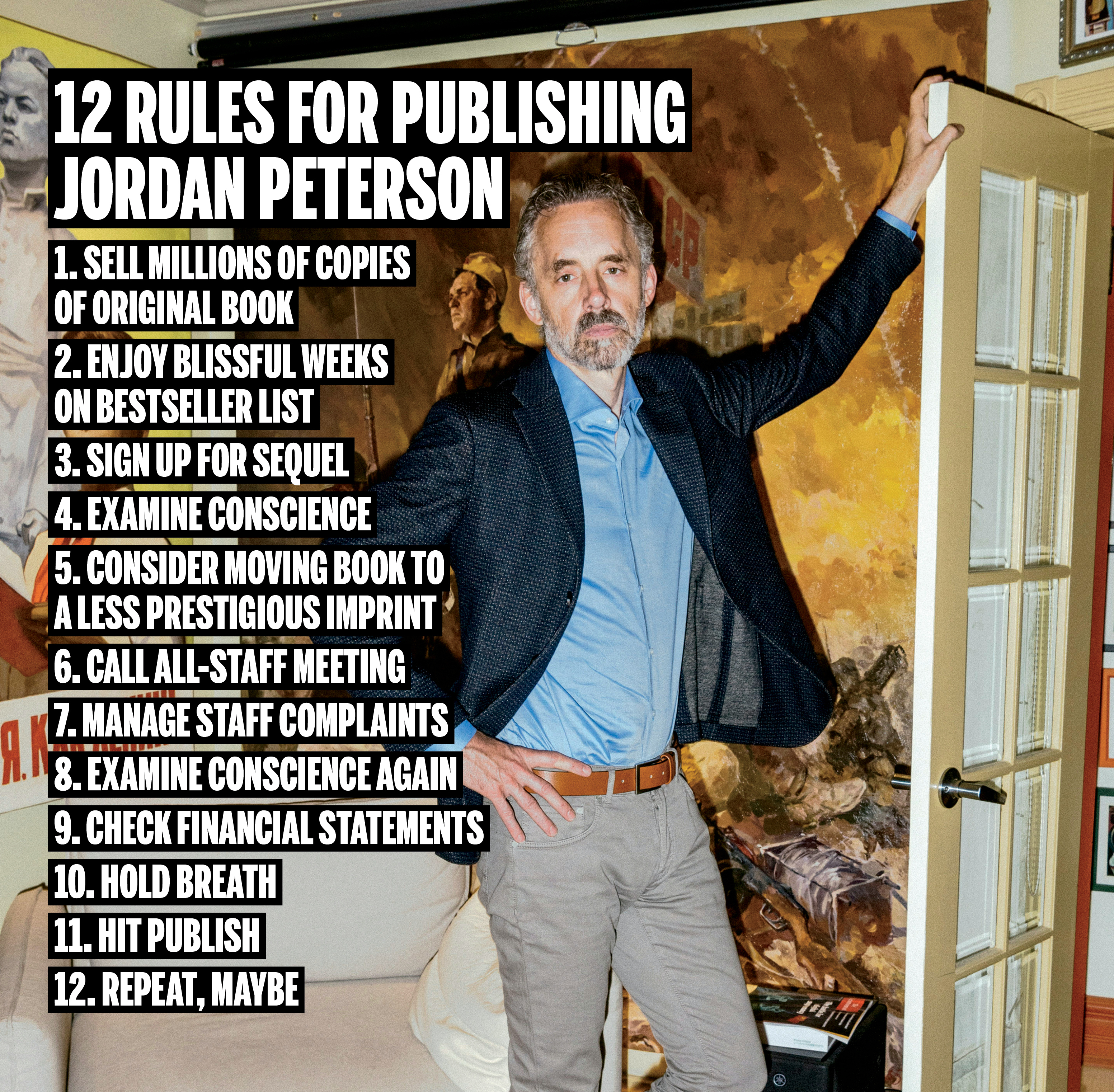

Peterson at home in Toronto, May 2, 2018 (Mark Sommerfeld/The New York Times/Redux)

Share

On March 2, Jordan Peterson, one of the most famous Canadians in the world, will publish his second book with Penguin Random House Canada (PRHC), by far the largest publisher in the country. Irrespective of whether Beyond Order: 12 More Rules For Life itself merits the attention, the release will be one of the publishing events of the year. In large part, that’s because Peterson, 58, has become literally iconic. A relatively obscure if popular professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, Peterson erupted into the zeitgeist in 2016 when he released “Professor Against Political Correctness,” a three-part YouTube video series that began by criticizing the federal government’s actions in adding gender identity and expression to Canada’s prohibited grounds of discrimination.

Peterson went on to portray himself as a free speech crusader, denouncing Ottawa for turning dictated gender pronouns into “compelled speech,” and expanding outward into railing against “cultural Marxism” and “radical left political” machinations. In his own words, the psychologist “hit a hornets’ nest at the most propitious time.” By 2018, as his videos racked up millions of viewers and his first PRHC title, the self-help tome 12 Rules For Life, became a massive international bestseller, Peterson was the culture war incarnate. To his fans, he is the unanswerable intellectual scourge of political correctness; he’s been described as the “acclaimed public thinker [who] offered eternal truths applied to modern anxieties.” To his critics, he is the living symbol of “hate speech and transphobia and white supremacy.”

The first quotation sits on PRHC’s website; the second was uttered by one of the publisher’s employees, as reported by Vice, at an open company-wide virtual meeting. And that’s the other reason March 2 will be one of the Canadian book trade’s notable days in 2021. Publishing has had a long history of episodes of cognitive dissonance between its body and soul, or, to be more precise, its self-image as an urgent cultural voice—increasingly for the marginalized and otherwise voiceless—and its practical needs as a profit-seeking enterprise. But 2020 unfolded as an exceptional year of reckoning for publishing in Canada and abroad, a reckoning that has continued into this year.

Since its Nov. 23 announcement—informing the public and its employees on the same day—of Beyond Order’s forthcoming release, PRHC has remained tight-lipped about it. Very few of the employees Maclean’s reached out to want to make any kind of comment, even unofficial, and none want their names revealed. Those who are willing to speak focus on three main issues: the social media and online reaction to what became known of the company-wide meeting; how publishing, writ large, should weigh its moral responsibilities; and how the employees themselves are now rethinking their concepts of their workplace.

The level of response is much the same among PRHC’s growing array of diverse authors. Most of those Maclean’s contacted either did not respond or said they were unwilling to comment. A handful said they feel “conflicted” about the Peterson publication, primarily because of what they describe as deeply positive interactions with the company’s highly regarded editors, publishers and publicists. One prominent author, speaking off the record, finds that contradictions abound, even in the author’s own heart. The times call for a “self-critical mood, and impatience for real—not cosmetic—change is necessary,” says the writer. “Yet, I think believing that publishing can reflect the world more truthfully, while also believing that expression must be curtailed—as determined by publishing houses—are not easily compatible beliefs.”

Among the few writers willing to speak openly is one who sees no difficulty in holding both convictions. Kristen Worley is the author of 2019’s Woman Enough: How a Boy Became a Woman and Changed the World of Sport, a memoir about her life that also details her successful challenge, as an Olympic-level cyclist and XY female, to International Olympic Committee policies that were not reflective of human diversity. She now works with the IOC “to find effective remedies for the international sporting industry.” In terms of its worldwide network and influence, says Worley, Penguin Random House resembles the IOC itself, and like the international sporting industry, should “pivot” from a top-down leadership style to a bottom-up stewardship model. Only then will publishing be able to positively reflect the range of human diversity. “People are immersed in different stories and life experiences,” she says, “and making those available is important for the growth and vitality of our society. A global publisher like Penguin has the potential—as a storyteller, influencer and steward of best practices—to positively impact individual lives and the very fabric of communities worldwide.”

If that is an oblique critique of PRHC’s Peterson position, prominent social entrepreneur Andreas Souvaliotis is more blunt. “Publishers and media, like Maclean’s, for instance, or Facebook, have to navigate a very fine line,” says the author of the 2019 memoir Misfit: Autistic, Gay, Immigrant, Changemaker, “between freedom of speech on one side and lies or explicitly hate-inducing stuff on the other.” He doesn’t think Peterson—despite holding a slew of opinions Souvaliotis considers “odious, extreme, miserably negative and potentially even dangerous”—can or should be banned from publication. But neither does he think PRHC was wise to take him on. “I’m a business guy. I know exactly where the vulnerabilities of a business can be in terms of image and reputation. A publisher has to really think hard before taking on unsavoury authors like Peterson, precisely because it may alienate its employees or its supply chain, which is authors. You’re a publisher in 2021, when everybody is thinking very, very hard about mutual respect and inclusion, and you have an extremely precious commodity in your talent, your employees: do you really want to publish this sh-t?”

A century ago, publishing’s clashes swirled about potential responses to obscenity laws; today they are a reflection of how rapidly the book trade’s Overton window—its range of acceptable opinion—is changing, especially among its younger and more socially progressive employees. One staffer, who linked their shock directly to their “love” for PRHC’s commitment to diversity and inclusion, told Maclean’s that the Peterson announcement “felt like a slap in the face to everything that [the company] had said and had agreed to do just beforehand” in the wake of George Floyd’s May 25 death under the knee of a Minnesota police officer. Another employee, far more mindful of PRHC’s commitment to turning a profit, saw the staff anger and anxiety from a different angle: “It’s the posturing. The company has profited from its moral stance,” they said, referring to the number and stature of racialized and other minority authors PRHC has published and also in the way so many people employed there “feel an investment in the company, and that it has the same kind of moral standards and the same political standards as they do.”

Sue Kuruvilla, who in January became publisher of Random House Canada—the prestigious PRHC imprint that will release Beyond Order—responded to a request for comment by Maclean’s: “One of my core values as the new publisher of Random House Canada is to profile a wide variety of opinions, voices and perspectives. We must reflect and amplify a diversity of viewpoints—both within our organization and in the books we publish. Sometimes, that means publishing ideas and perspectives that some will disagree with. A decision to publish an author does not always mean we all must agree or disagree with their views. Discussion and debate are the foundation of better understanding.”

The combination of authorial celebrity and publisher clout—PRHC publishes or distributes more than half the books in Canada, a percentage that will only increase after its parent company finalizes its US$2-billion acquisition of Simon & Schuster—makes the Peterson clash particularly newsworthy here. But it’s far from the first Canadian instance. In an interview, independent publisher Jack David, co-founder of Toronto-based ECW Press, recalls incidents as far back as 1982 when some staffers, apparently unaware of Christ’s words to St. Paul in Acts 9:5-6, found the title of John Metcalf’s Kicking Against the Pricks to be offensive (in fact, it’s a reference to what Christ saw as Paul’s futile, self-harming persecution of Christians). More recently, simply mentioning the name Karla Homolka, in regards to an opportunity to publish the English translation of her prison roommate’s Pillow Talk, meant “I was shut down,” says David. “If I’d gone ahead with it, I would have been working on my own.”

By “on my own,” David means the compromise he made with employees three years ago when ECW published George Bowering’s novel No One. “George, who I’ve known for years, was playing with fiction and memoir. The narrator, named George—but not George Bowering—was a university prof who goes to conferences with the hope of meeting women and bedding them. He’s also involved in a complicated marital relationship. So, 80 per cent of the book is dealing with an academic on the loose, a kind of Rake’s Progress, and then the whole book changes because his wife turns the tables on him in the last 15-20 pages.”

READ: Jordan Peterson’s people are not who you think they are

Staffers’ objections were that the novel was misogynist and used the narrator to shield the real Bowering from any responsibility for his real-life actions. David, who thought No One was a good novel, went ahead with publication, “but the publicity devolved to me,” he says. “That meant making phone calls and sending out books and doing things I hadn’t done in 20 years, because I didn’t want staff to do stuff they didn’t want to.” It didn’t end well. Bowering, his wife and his friends were all upset with the publicity efforts while those who disliked the novel as a concept, including media reviewers who wouldn’t touch it, remained unhappy. Soon, “people who had been friendly to me were no longer talking to me,” says David, and that was on both sides of the divide.

Similar disruptions have lately roiled other media as well, including most notably, Twitter, which—after years of employee pressure on CEO Jack Dorsey—suspended Donald Trump’s account in the wake of the assault on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. But publishing has the most money at risk in such disputes—Peterson’s first book has sold five million copies worldwide, bringing PRHC, which had global rights to it, tens of millions in profit. It also has the largest young workforces and the biggest collective platform. The industry has faced the brunt of high-profile discord between employers and employees, and at an increasing pace in the past year.

In March 2020, dozens of Hachette employees staged a walkout from its New York offices to protest against the publishing giant’s decision to take on Woody Allen’s autobiography, Apropos of Nothing, under its Grand Central imprint. The comedian and director has long been accused by his daughter, Dylan Farrow, of molesting her as a child in the early 1990s. Ronan Farrow, Allen’s son, who strongly supports his sister, is the author of one of the most significant books to emerge from the #MeToo era, Catch and Kill, released by another Hachette imprint. “It’s a huge conflict of interest and wrong,” said one anonymous Hachette employee to a journalist. Hachette CEO Michael Pietsch exacerbated the anger when, in an interview with the New York Times, he set out a publishing ethos: “each book has its own mission.” Ronan Farrow responded to Pietsch in an email that Hachette’s declaration of editorial independence between its imprints effectively meant that “as you and I worked on Catch and Kill, [addressing] the damage Woody Allen did to my family . . . you were secretly planning to publish a book by the person who committed those acts of sexual abuse.” The following day, Hachette dropped Apropos of Nothing.

Three months later, numerous Hachette staffers in London told their employer during a meeting that they didn’t want to work on a new young readers’ book by J.K. Rowling, because of the Harry Potter author’s well-known anti-transgender comments. This potential mutiny was averted when Hachette argued that whatever Rowling’s opinions on trans people, she was not expressing them in The Ickabog. In a statement that seemed to green-light future employee actions, the publisher said, “We will never make our employees work on a book whose content they find upsetting for personal reasons, but we draw a distinction between that and refusing to work on a book because they disagree with an author’s views outside their writing, which runs contrary to our belief in free speech.”

By June, a third cause gripped the industry, after Floyd’s death. Across the U.S., with echoes elsewhere including Canada, massive Black Lives Matter demonstrations were forcing reckonings in all kinds of institutions and businesses. Anti-racism books like Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Anti-Racist and Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility shot up North American bestseller lists, while Black authors began collecting the information to show what they already knew: they weren’t as well-paid as their white counterparts.

Publishers responded with strong promises of the sort that excited the PRHC employee who was later shocked by the Peterson announcement, commitments to increase diversity and inclusion among workers and authors both. These were genuine and sincere pledges, (almost) everyone who has commented agrees, but they did not change publishing’s ruling ethos. Every book is a distinct individual; releasing titles with diametrically opposing viewpoints—the memoirs of a sexual abuser alongside a book denouncing sexual abuse, for instance—says nothing about a publisher’s own moral stance. And, in a distinction meaningless to anyone outside the book trade, every imprint has its own DNA and publishes very different books from other imprints, even when owned by the same publisher.

READ: This publisher’s first thriller broke pre-release sales records

When Penguin Random House (PRH) in the U.S. quietly acquired Beyond Order in 2019—in retrospect, virtually an assurance that PRHC would also publish it—New York staff were also unhappy. But PRH’s head office dampened employee discontent by moving the book from its first company home—the actual Random House marque—to the less prestigious Portfolio imprint, home to Dilbert comic collections and conservative business-oriented titles. That is significant to employees, but for readers it’s still PRH. Likewise, Missouri Republican Sen. Josh Hawley, who lost his book deal with Simon & Schuster after fist-pumping the Capitol riot mob, found a new home for his anti-Big Tech book with conservative publisher Regnery, as was widely expected. Regnery is distributed worldwide by Simon & Schuster, making the major publisher’s rejection of Hawley virtue-signalling at its finest.

As a tumultuous year in publishing drew to a close—and that’s without mentioning COVID-19—the November Canadian announcement about Peterson struck a hornets’ nest every bit as lively as the one the psychologist hit in 2016. To his critics, Peterson is on the wrong side of every major cause: #MeToo, trans rights and Black Lives Matter. Nor will Beyond Order be a cash machine on the level of its predecessor, since PRHC has only Canadian, not world, rights this time around. In Canada, it has not been shuffled off to a less prestigious imprint. There is a degree of bafflement and disappointment among employees for all those reasons, according to those who will talk about it. And anger, too, not only against the company but also the condemnatory stream of right-wing reaction that came their way after news of their virtual town hall became public.

It made news stories around the world, the majority of which noted the tears in one staffer’s eyes in their headlines, the better for right-wing media to hammer people they often refer to as sad snowflakes. Mikhaila Peterson, Jordan’s daughter and his primary publicist, tweeted: “How to improve business in 2 steps: Step 1: identify crying adults; Step 2: fire.” In response, the staffer who was critical of PRHC “posturing” noted that publishing “doesn’t pay well” in actual monetary terms. “The trade-off for that has been the cultural capital you get from it, which makes people feel they have a more evolved workplace and a stake in that.” And when the public announcement and the town hall meeting—arranged with four or five hours’ notice—come on the same day, “you know the decision has already been made.” That made an “ironic joke” out of the company’s offer of crisis counsellors for “a so-called crisis of its making,” according to the same employee.

There were also valid questions raised about security, said the second employee, including in publicity, marketing and sales, all of which might be lifted—sources were unsure—from the shoulders of the unwilling in the manner of Jack David taking on publicity for No One. (In that regard, a 2018 remark from then-PRHC CEO Brad Martin probably points to one factor in signing up Peterson, with his army of YouTube viewers: contemporary publishing’s most prized non-fiction authors “come with a ready-made following.”) “Are angry people going to descend on our offices?” asked that staffer. Publishers make the argument that there is a distinction between the publisher and what it publishes, “but that’s not clear outside, because more and more often people are finding the publisher who published that work and coming after them,” they added. “And why shouldn’t we only publish what reflects our values? We’re a private company, and we get to choose who we publish.” Perhaps so, says the other employee while also noting that the company regularly publishes or distributes, without attracting the scrutiny that accompanies a Peterson title, a steady stream of revenue-producing books most staff probably disagree with. “Last year we published—without any noise—Dave Rubin’s Don’t Burn This Book, and he was literally the opener for Jordan Peterson on tour.”

As for not listening to employee objections—or making a decision and then listening—it’s not just Souvaliotis who finds that idea toxic for employers. ECW’s Jack David simply laughs. “We hire people who are smart and responsible, and we especially like them when they’re feisty. So we listen to them.” Publishers realize the free speech argument is no longer the killer app, the one that shuts up all opposition, not when the opposing side thinks the speech is both false and harmful. But as long as there is a mismatch between the values and politics of an increasingly diverse junior workforce and its more traditional, in every sense, higher-ups, publishing (and other media) will keep having these moments. One could prove epic. The industry is already buzzing: about the cash value and moral swamp involved in weighing whether to publish, should it ever see the light of day, Donald Trump’s presidential memoir.

This article appears in print in the March 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “12 rules for publishing Jordan Peterson.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.