Neanderthals vs. man’s best friend: Book review

Shipman presents evidence that seems to push the domestication of dogs back to the era of the Neanderthals’ demise

Share

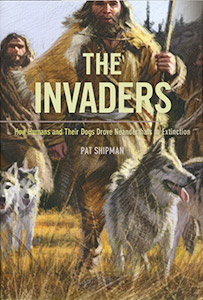

THE INVADERS: HOW HUMANS AND THEIR DOGS DROVE NEANDERTHALS TO EXTINCTION

Pat Shipman

Once upon a time, Homo sapiens was not alone on this planet. For more than 200,000 years, Neanderthals—close relatives who shared 99 per cent of our genome—flourished across northern Eurasia as stocky, cold-adapted apex predators who made stone tools, cared for their injured and buried their dead. Then, around 45,000 years ago, modern humans, who had evolved in Africa some 150,000 years earlier, arrived in Europe. Within five millennia, Neanderthals were gone—albeit not completely: One to four per cent of the genome of non-African humans is Neanderthal, the result of interbreeding or traces of a species ancestral to both groups.

Ever since the first discovery of Neanderthal bones, scientists have been grappling with two questions: What distinguished the two branches of humanity from each other? and, What happened to our cousins; why did they die while we lived on? There has been no end of theories: We hunted down and killed them; we killed them accidentally with a pathogen brought from Africa; a particularly brutal cold snap did them in; we out-thought or out-hustled them for resources; all or some of the above. Lately, the pendulum seems to have swung to a rough equality between the two hominin species, with an edge—perhaps the most crucial edge—to modern humans in a capacity for cultural innovation.

Shipman, an anthropologist, brings two new ideas to the debate in her cautious but compelling argument. The first draws on the insights of invasion biology. It’s instructive, Shipman notes, to consider the behaviour of wolves after they were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park 20 years ago. Their first order of business was killing the coyotes that had flourished in the wolves’ absence—that is, destroying the competition.

Her second point is to present evidence that seems to push the domestication of dogs much further back in time than usually believed, back to the era of the Neanderthals’ demise. Our ancestors may not have been able to out-compete Neanderthals on their own, but that edge in adaptability sparked a brilliant idea, one Neanderthals seem never to have considered. Turning wolves into dogs—forging an alliance of two apex predators—made us unstoppable. Shipman is agnostic about whether there was genocidal violence directed at Neanderthals, but she points out how modern humans have never been keen on sharing resources with other species—except dogs, man’s best friend.