New biography illuminates J.D. Salinger’s work

Thomas Beller’s fascinating biography ignores Salinger’s life in favour of his work

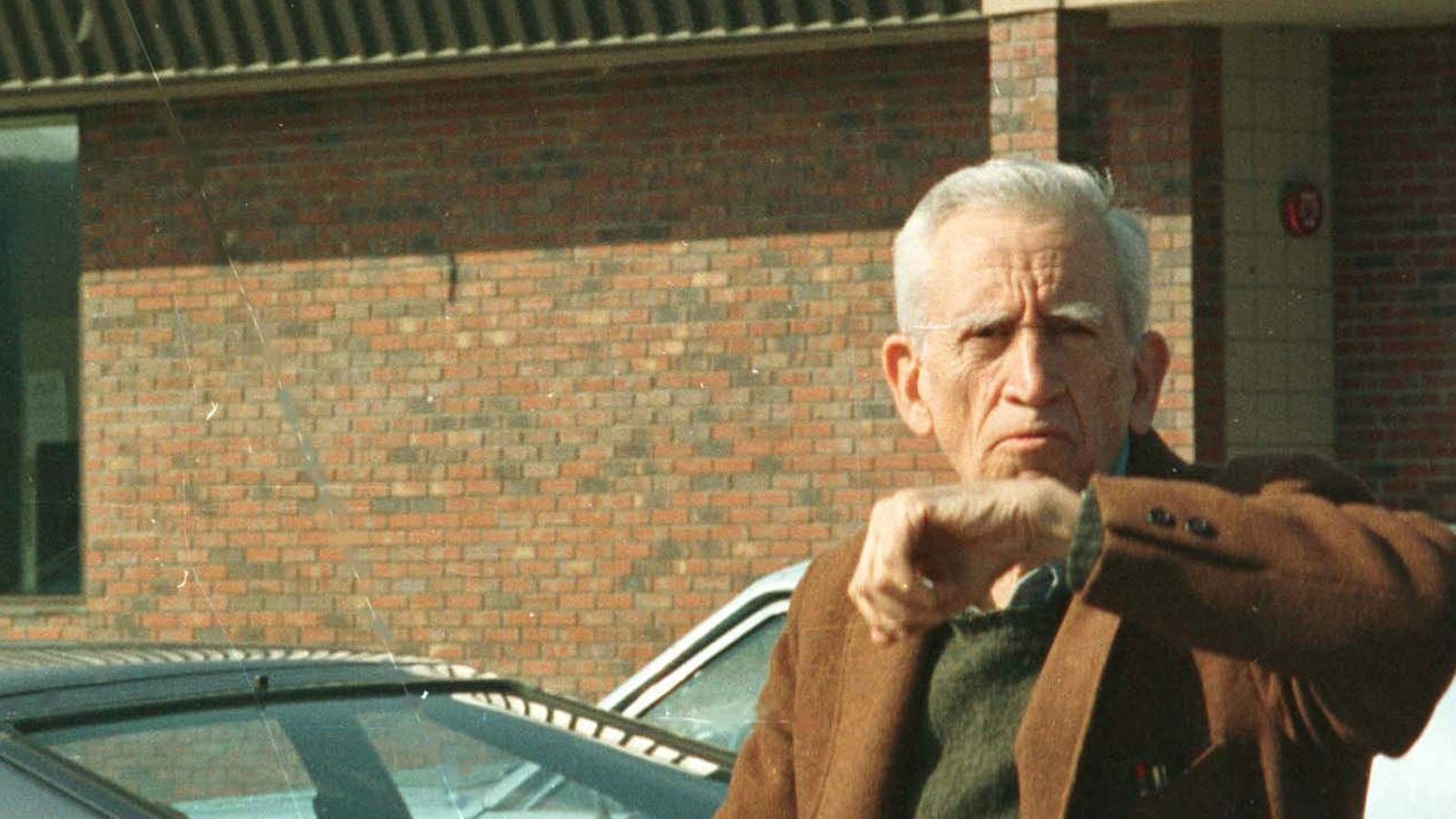

EXCLUSIVE TO INF. ALL-ROUNDER.

Share

Anyone who wants to know what J.D. Salinger, the Hermit of Cornish, was really doing up there in the wilds of New Hampshire, anyone who sympathizes with his can’t-stand-it-anymore neighbours who, Time magazine reported in 1961, “not long ago, put on dungarees and climbed over the 6½-foot fence to take a look around,” should skip over Thomas Beller’s biography of the author of The Catcher in the Rye. Beller is willing to denounce the media’s “neurotic” fascination with a writer who won’t speak to journalists, but he couldn’t be less interested in speculating about what, exactly, Salinger was keeping private. Or, perhaps, on second thought—for J.D. Salinger: The Escape Artist is a book of gracious and provocative second thoughts—the achingly curious are exactly who should read it.

“The year Time descended upon Cornish—the dungarees moment—marked the time when Salinger made the transition from highly regarded writer to myth,” says Beller in an interview. “And his story went away from what was interesting about a writer who was really good at ambivalent characters, to the uninteresting—to a cat-and-mouse story.” Beller, 49, is a short-story writer whose geographical and cultural milieus are Salinger’s, albeit a generation after, right down to the fact that Beller’s father and Salinger—briefly and without meeting—were both teenaged Jews in Vienna before the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938. It’s a familiarity that gives Beller a unique perspective on a literary master of “brevity and ellipses”—an escape artist in many senses—whose iconic status absurdly rests on his later-life silence.

The result is the polar opposite of previous attempts at Salinger’s life, books that seem the work of “self-aggrandizing burglars” to Beller. Instead, he offers a biography that brilliantly speculates on how The New Yorker may have influenced Salinger before he was published in it—the writer’s stationery mimics the magazine in font and style—while barely flicking at entire marriages, including one to a low-level Nazi.

The book is as elliptical as a Salinger story, opening with the tale of four-year-old Jerome David, dressed in his Indian costume and provisioned with a suitcase full of toy soldiers, attempting to run away from home—early escape proclivity—and then moving to Beller’s temporary acquistion of a rare surviving copy of a previous Salinger biography, a book Salinger managed to block from publication. The Escape Artist is also suffused with the inextricably linked themes of letters and betrayal: “Every other [Salinger] story involves someone fishing a letter out of their pocket”—and letters were how his now-former friends betrayed him, by allowing biographers access. (Salinger’s successful assertion of legal control of his letters doomed the older biography.)

It is only due to the fact that Salinger is dead that Beller will poke, however gingerly, into his life at all. (Beller, no burglar, is so reluctant to look into the letters laid bare in the rare book he borrows that he even manages to temporarily lose it.) His emphasis on Salinger’s writing as the sole interesting part of his legacy is best captured by an exchange with a friend. She told Bellor her daughter’s teacher claimed there were only two things students needed to know about Salinger: “He was a child molester and he was a symbolist.” Beller’s response was to spend a few minutes trashing the “symbolist” label.

It’s an arresting moment in a book that manages to be extraordinarily informative about Salinger almost entirely through his work. But isn’t “child molester” a bridge too far, an accusation that must be faced? Beller does eventually respond, but (naturally) in an indirect way. He allows that Salinger “being a serial seducer of college-age girls does start to look ugly after a while.” But that lurid claim has other roots, too: Salinger may have recoiled from the modern cult of celebrity before anyone else, but he miscalculated his response, Bellor says: If you won’t talk to anyone and excommunicate anyone in your life who does, then “you leave the field to the crazies.” And what you care about, your work, can slide out of mind. Unless you’re lucky enough to have Tom Beller for a biographer.