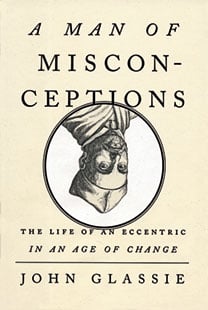

Review: A Man of Misconceptions: The Life of an Eccentric in an Age of Change

By John Glassie

Share

Athanasius Kircher of Fulda (c. 1601-1680) occupies a strange niche in intellectual history. Kircher, a German Jesuit who founded a museum of curiosities and wonders in Rome, pops up in the early, confused history of dozens of scientific disciplines, from acoustics to geology to sinology. He was one of the most famous and prolific scholars in Europe, yet his library-filling oeuvre has left no trace of value. He has recently become a favourite among students of early-modern weirdness, evolving from being forgotten to being remembered for being forgotten.

Athanasius Kircher of Fulda (c. 1601-1680) occupies a strange niche in intellectual history. Kircher, a German Jesuit who founded a museum of curiosities and wonders in Rome, pops up in the early, confused history of dozens of scientific disciplines, from acoustics to geology to sinology. He was one of the most famous and prolific scholars in Europe, yet his library-filling oeuvre has left no trace of value. He has recently become a favourite among students of early-modern weirdness, evolving from being forgotten to being remembered for being forgotten.

John Glassie’s affectionate portrait accounts for much about this man’s evaporating importance. Father Kircher was wrong about most everything he turned his mind to, and when he was right it was mostly dumb luck. As a student of Egyptian hieroglyphics, for example, he had the good sense to suspect that the contemporary Coptic language of Egypt might provide clues to the lingo of Pharaonic Egypt. But while this hint would be used in the 19th century to help crack hieroglyphics, Kircher squandered it, improvising hundreds of pages of worthless but attention-grabbing “translations.”

His greatest contemporaries saw through Kircher: the Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens called his work “the nonsense of fools,” and René Descartes agreed the Jesuit was “more of a charlatan than a scholar.” Kircher was indeed a congenital exaggerator, full of fun but ludicrous tales about his own life (which Glassie obligingly explores). Regrettably, he wasn’t much of an experimenter, he was gullible about the exaggerations of others and he never did get a handle on cutting-edge math. Although Kircher had his defenders, the learned world eventually came to agree with Huygens and Descartes, imparting a rather sad ending to Glassie’s story of an extraordinary life.

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary