‘Why people choose to hang off rock faces hundreds of feet above the ground’

A review of ‘The Best of Mountain and Wilderness Writing’

IMAGE DISTRIBUTED FOR BREITLING – Yves Rossy, known as the Jetman, flies over the snow-capped peak of Mount Fuji, Japan, during his first flight in Asia. The Swiss aviator flew over the famous landmark mountain at speeds of up to 185mp/h (300km/h) with his Jet powered carbon-Kevlar Jetwing which he uses his body to steer. (Katsuhiko Tokunaga/Breitling for Photopress via AP Images)

Share

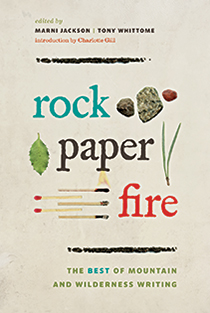

Rock Paper Fire: The Best of Mountain and Wilderness Writing

Rock Paper Fire: The Best of Mountain and Wilderness Writing

Edited by Marni Jackson and Tony Whittome

There is something inherently similar about climbing a mountain and sitting down to write—both involve mining the soul. Which is why a workshop devoted to “mountain and wilderness writing,” such as the one introduced at the Banff Centre in 2005, makes perfect sense. This eclectic anthology is a product of that workshop and includes memoirs, essays, poetry and fiction. Each piece offers a unique meditation on why people choose to hang off rock faces hundreds of feet above the ground, sleep on precarious ledges of ice, and cross the country by canoe and foot. The answer always seems to come down to the same reason most writers give for subjecting themselves to the solitude and insecurity coincident with setting words down on a page: They have to.

This imperative is movingly captured in “Into the Mountains,” by Niall Grimes. After the death of his mother, Grimes found himself in a rented car driving to Donegal, on Ireland’s northwest coast. This was where, as a teen, he’d discovered climbing, combing the craggy hillsides for clean, steep rock to grab hold of. The landscape is at once forbidding and addictive, “a land you yearned for, even in its presence.” As he travels through it, memories of previous expeditions flood in and Grimes tears up—the memories are good, but combined with his grief, almost too poignant to bear. And then suddenly he reaches his destination, the one he didn’t even know he had, and completes a first ascent, at the same time finding some peace in his loss, beauty in his sadness.

Death—or the threat of it—is, not surprisingly, a theme in the book. “Surge,” an eerie excerpt from Erin Soros’s forthcoming novel, Hook Tender, deals with the decision to leave behind those who are weaker or more afraid. And in “Transgressions,” Katie Ives explores the ethical dilemma of writing about dangerous adventures, which “encourage readers to take part in activities that might kill them.” Her only defence, she concludes, “lies in the absurdity of beauty, a force that seems, at times, as unpredictable and overwhelming as grace.”

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary.