Rogers Writers’ Trust: Spotlight on David Chariandy

We asked the 2017 nominees: Do you consider yourself a politically engaged writer? How does that affect your work?

Share

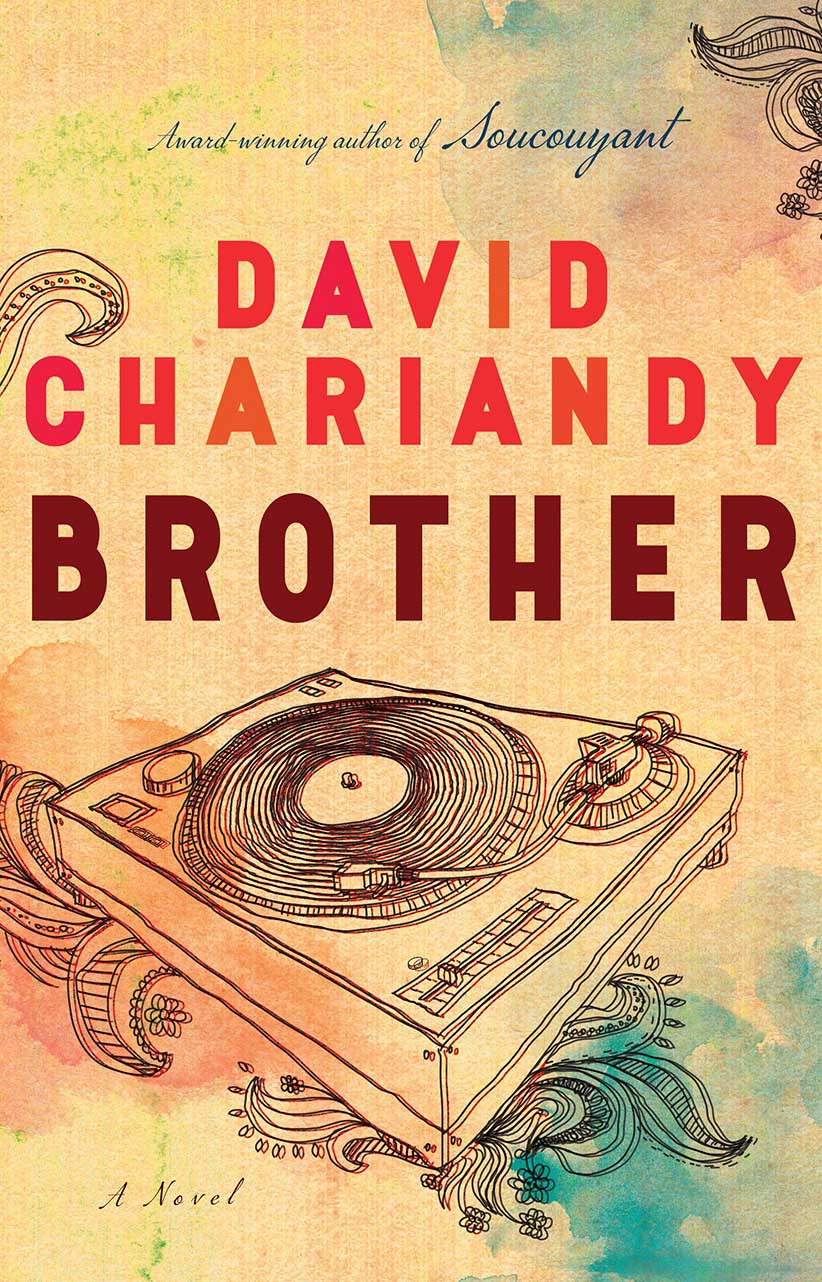

David Chariandy is nominated for the 2017 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize for his novel Brother. The winner will be announced at the Writers’ Trust Awards ceremony in Toronto on November 14. The winner of the newly enriched award receives $50,000. Each nominee receives $5,000. During the weeks leading up to the event, Maclean’s will publish an excerpt from each shortlisted writer, along with their answer to this one question: Do you consider yourself a politically engaged writer? How does that affect your work? Here is Chariandy’s response.

I do insofar as I believe that language and representation matter, that people live or die through the power of words and through the stories they either tell for themselves or else have told about them. I guess I’m “politically engaged” in that I feel compelled to think very hard and long about what to write and especially how to write – and also about who gets to write in the first place. At the same time, I can think of few uses of language more boring, cynical, and sometimes outright violent than the rhetoric and narratives of mainstream politics. Writing and reading have offered me precious relief from that painfully restrictive business of “the political,” and helped me return to the urgent and sublimely complex work of life both seeing more and feeling differently.

Excerpted from Brother, copyright © 2017 by David Chariandy. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

She was overseas when she got the news that her father had been admitted into intensive care, and during her phone call to me she described how her mind instantly filled with panic but also vague anger. In his occasional letters to her, he had mentioned that he was feeling tired, but he had not admitted the cancer. She caught a long series of connecting flights to Toronto, and then a Greyhound bus to the hospice in Milton, the small town he had moved to only recently. She stayed with him for the week until the end, and there had been time to talk but not nearly enough. “What was there to say?” she asked me afterwards with a quiet impossible for me to fill. This call out of nowhere. “Please visit,” I said to her, doubt creeping into my voice even as I repeated myself. “Come home to the Park.”

The Park is all of this surrounding us. This cluster of low-rises and townhomes and leaning concrete apartment towers set tonight against a sky dull purple with the wasted light of a city. We are approaching the western edge of the Lawrence Avenue bridge, a monster of reinforced concrete over two hundred yards in length. Hundreds of feet beneath it runs the Rouge Valley, cutting its own way through the suburb, heedless of manmade grids. But the Rouge is invisible to us tonight, and we have just arrived at the Waldorf, a townhouse complex at the edge of the bridge and made of crumbling salmon brick, flapping blue tarps draped eternally over its northeast corner. The unit where Aisha lived ten years ago with her father is on the prized south of the building, away from traffic. But the side where I have remained all my life is at the busy edge of the avenue, exposed to the constant hiss of tires on asphalt. I warn Aisha about the loose concrete on the doorsteps and suffer a sudden bout of clumsiness working the brass key into the lock. I push open the door to show a living room lit blue with the shifting light of a television, its volume turned off. There is a couch with its back towards us, and on it there is a woman with greying hair who does not turn.

I gesture to Aisha that we should be quiet. I remove my shoes in a demonstrating way, and with our coats still on I quickly guide Aisha across the living room. The woman on the couch continues to watch the silent television, the mime of a talk-show interview, a celebrity guest throwing his head back in laughter. I lead Aisha down a short hallway to the second bedroom. A small lamp casting a circle of light upon a desk, a bunk bed with a mattress and sheets on the lower bed only, the upper bunk long ago stripped bare, even the mattress removed, leaving skeletal slats of wood. I close the door behind us and in the sudden smallness of the room begin explaining. We won’t be sleeping together on the bed, of course. I’ll be using the living room couch, which is quite comfortable, honestly. I point out the towel and extra blankets set out very obviously on the sheets of the lower bunk. I stop when I notice that Aisha is staring and that she hasn’t let her backpack touch the floor.

“Your mother doesn’t speak anymore?” she asks.

“She speaks. She’s just quiet sometimes, especially at night.”

“I’m sorry,” she says to me, shaking her head. “I shouldn’t have come. This is an intrusion.”

Bullets of slush smattering upon the bedroom window. Another truck that has passed too close to the curb outside. But in the wake of sudden noise, a feeling creeps upon me, one of shame, maybe, for imagining that I could try to end our conversation tonight like this. With talk of sleeping arrangements and towels. With acknowledgement of Aisha’s father, yet no acknowledgement of that other loss shadowing this room and measured in the ten years of silence between us.

“I still think of Francis,” she says.