Saying goodbye to Toronto’s Cookbook Store

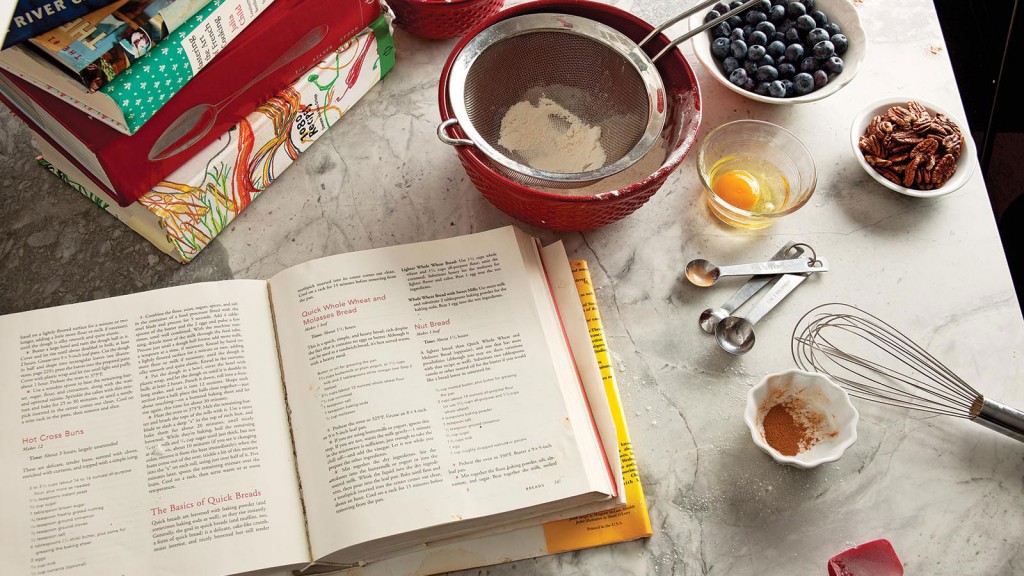

How to bid farewell to a store beloved by writers, chefs and foodies alike? With a potluck, of course.

Share

There wasn’t a murmur in the room, not a ripple, when famed British chef Fergus Henderson walked into the farewell-potluck-cum-wake at Toronto’s Cookbook Store last Sunday. That wasn’t surprising. Before the independent bookseller closed in early March after 31 years, it was a frequent stop for the mounting roster of touring food celebrities—Martha Stewart, Julia Child, Anthony Bourdain, René Redzepi, Jamie Oliver, Nigella Lawson, Henderson himself. So there was an odd logic in the founder of London’s St. John restaurant, the man who coined “nose to tail” cookery, miraculously popping in to pay his respects.

Alison Fryer, the store’s manager from Day 1—April 6, 1983—made her way through the crowd gathered in the 650-sq.-foot space, its blond shelves eerily empty, to greet Henderson with a hug. Meanwhile, chefs, restaurateurs, food writers and former staffers and patrons reminisced by tables laden with homemade offerings—Yotam Ottolenghi’s “smashed potatoes,” Lawson’s Coca Cola cake, patisserie-perfect raspberry-vanilla macarons, Claudia Roden’s Mediterranean dips. Cookbook author and caterer Dinah Koo, who owns the Dinah’s Cupboard food shop nearby, popped in all the time to exchange ideas: “It was a hub, ground zero,” she says. “If you were ever sad, you’d just come here and you wouldn’t be.” When asked what the store meant to him, winemaker Charles Baker paused: “Everything,” he said. “When I worked in restaurants, it was my source for answers; when I moved to wine, it was a source; I watched a generation of cooks, servers, sommeliers come through here.”

At the centre of it all was Fryer, an ebullient woman with laser-sharp intelligence and formidable networking skills. Former staffer Kevin Jeung, now a chef, recalled Fryer brokering an apprenticeship for him at the renowned Spanish restaurant Mugaritz. Ferguson, too, had fond memories: “Marvellous, marvellous store,” said the chef, in town to cook for a pop-up supper club. “I hope they find a way to resurrect.”

Even if that were in the cards, a sequel could never equal the original’s singular trajectory, one that mirrored the elevation of the cookbook, from utilitarian The Best of Bridge tome aimed at housewives putting meals on the table to sacred coffee-table objets—Thomas Keller’s The French Laundry published in 1999, Nathan Myrvold’s spectacular $600 six-volume, 21.4-kg Modernist Cuisine in 2011. Optometrists and early “foodies” Josh Josephson and his then-wife, Barbara Caffrey, were prescient when they opened the store in a building owned by Josephson’s family, undeterred by the fact that the cookbook shop previously in the location had gone belly-up. Fryer (then Alison Day), newly graduated from university, balked when she learned the bookstore job she was interviewing for was cookbooks: “I thought, ‘Crap, I don’t know a lot about food.’ But I’m really gung-ho, so we hit it off.”

The bestsellers in their first year signalled seismic shifts: Martha Stewart’s Entertaining introduced Martha, big, glossy production values and the “aspirational” mantra; the first Silver Palate Cookbook with its arty, hand-drawn black-and-white graphics made photographs seem passé; Soho Charcuterie ushered in the hot-restaurant cookbook; and the unexpected hit was Muffin Mania, a 70-page book banged out on a Selectric typewriter and self-published by Cathy Prange and Joan Pauli, two sisters from Kitchener, Ont. There would be a similar sleeper every season, says Fryer; a more recent example: Quinoa 365.

A decade later, the Food Network reinvented the cookbook genre by creating a new celebrity caste system. Meanwhile, the Internet was proving both aid and impediment: It gave the store an online platform, but put it in competition with online discounters, a threat exacerbated by the arrival of big-format bookstores, two of them just blocks away.

The store’s trump card remained the community it cultivated from the outset. “We didn’t just want to be part of the food community,” says Fryer, “we wanted to be part of the community at large.” They exploited their corner location with arresting windows done on a shoestring. For a fundraiser for AIDS hospice Casey House in the late 1980s, they brought in drag queens to strut in the windows, transporting them by limo, Fryer recalls: “We were worried for their safety. There was still a lot of prejudice.” The effort was worth it: “People went nuts.”

The store became a mecca—for cookbook signings, knife-skills classes, candid advice on anything culinary or the latest industry dish. Mark Bittman, Fryer confides, was difficult to wrangle. Louise Dennys, the publisher of Knopf Canada, called once to say she’d been offered rights for a British chef she didn’t know: “Can you tell me about this person, Nigella?” Fryer, who’d imported Lawson’s books for years, insisted they sign her: “She’s going to be huge.” They were even more supportive of Canadian authors, says cookbook writer Bonnie Stern.

Their helpfulness could net unexpected benefits: They were the first North American to sell Ferran Adrià’s elBulli cookbook in English because Adrià’s brother, pastry chef Albert Adrià, said they’d done him a favour. Jennifer Grange, on staff since 1983, says she doesn’t even remember Albert visiting: “Maybe we gave him a restaurant recommendation; it was just what we did for everyone.”

When the building was sold for condos last year, they looked for a new location, says Josephson. But “a perfect storm” of construction, bad weather and Amazon’s heavy discounting did them in. “How can you compete in a business plan with a company that outwardly says, ‘We make no profits?’ ” asks Fryer: “You can’t.”

The market for cookbooks as physical objects remains, even though people are turning online for recipes, she says, a point made by Julie & Julia author Julie Powell in The New Yorker last year: “Mastering the Art of French Cooking on the iPad is more practical, but it’s far less personal.” Google can yield hundreds of recipes for any given dish, with ratings, comments and stars, but it’s denuded. There’s the lack of context, of an author’s voice, of the broader sensibility found in a cookbook—not unlike the story that disappears when a store that anchored a community disappears. People read cookbooks for inspiration, for narrative, like the latest fiction, says Fryer. “We used to say that if we depended on people to actually use their cookbooks, we wouldn’t have stayed in business more than a couple of years.” She sees a disconnect between a food-obsessed culture and the ability to put food on the table. “People say they have no time to cook, yet they find two hours a day to be on electronic devices. They can reel off 10 best restaurants according to San Pelligrino, but if you asked them to roast a chicken, they couldn’t. They can’t make a roux. Recipes now have to spell those out; it used to be assumed.”

The outpouring of affection, and grief, from across the globe for the Cookbook Store caught them by surprise, Fryer says: “It feels like being at your own funeral.” She shares an email from a shocked customer: “I and many others took you for granted.” Social media, too, was abuzz with tributes: “I remember coming to your store, on a visit to T.O. 20 years ago, and deciding to become a chef THAT day. Thank you for that!” the Toronto chef Eric Wood tweeted. He was a 14-year-old growing up in Edmonton who loved to cook but never saw it as “a real job,” until he came across Andrew Dornenburg’s Becoming a Chef, he told Maclean’s. News that the store was closing was “like hearing they were tearing down the family home,” he says. When he visited days later, Fryer recognized him from his avatar and gave him a hug. “He was someone I had no clue we had touched. That to me said, ‘We did a good job.’ ”

Fryer is waiting for the dust to settle before deciding what’s next. Cook-book.com remains intact, and there’s talk of continuing to run events featuring interviews and presentations with the likes of Keller and Adrià: “I think there’s a new community to be formed, just not around bricks and mortar,” says Fryer, who still speaks like a bookseller, as she enthuses about Ruth Reichl’s upcoming novel, Delicious, David Lebovitz’s My Paris Kitchen, Laura Calder’s Paris Express. Unsurprisingly, publishers have approached her to write a memoir: Who wouldn’t want pithy dish from the front lines of the food revolution? Meanwhile, Fryer surveys the abundance of the Cookbook Store’s last supper with a rueful smile: “We’re going to have the best leftovers this city has ever seen.”