The battle to topple Vladimir Putin

A book review of “Kicking the Kremlin” by Marc Bennetts

Share

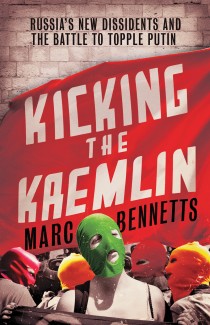

KICKING THE KREMLIN: RUSSIA’S NEW DISSIDENTS AND THE BATTLE TO TOPPLE PUTIN

KICKING THE KREMLIN: RUSSIA’S NEW DISSIDENTS AND THE BATTLE TO TOPPLE PUTIN

By Marc Bennetts

If Russian President Vladimir Putin were to invent fictional dissidents for the purpose of discrediting the movement seeking to end his long rule, he couldn’t do much better than the balaclava-wearing members of the feminist punk band Pussy Riot. Overtly sexual and contemptuous of Russia’s powerful Orthodox church, they enthrall Hollywood stars but inspire few Russians. “I would simply spank them and let them go,” opposition politician Boris Nemtsov said, in what amounted to a gesture of support during a court case against them.

British journalist Bennetts, a longtime resident of Russia, is clear-eyed about this, and much else besides. His insightful profile of Russia’s most visible dissidents is sympathetic, and rightly so—these are, for the most part, brave people fighting an increasingly repressive system led by an illiberal, czar-like strongman. But Bennetts does not shy away from probing their warts, including the hard nationalism of opposition figurehead Alexei Navalny.

The book is rich in context. Bennetts explains Putin’s rise against the backdrop of the turbulent 1990s—a time that left many Russians yearning for the stability Putin promised. He traces Putin’s deepening authoritarianism as a reaction to—among other factors—the so-called Colour Revolutions that toppled pro-Moscow governments in former Soviet republics, most notably, Ukraine.

Bennetts also explores the protest movement’s roots. Russia’s early dissenters took inspiration from the Colour Revolutions but couldn’t build on their momentum. Indeed, the best-organized rebels of the 1990s and early 2000s were not liberal democrats, but Eduard Limonov and his National Bolshevik street thugs. Putin’s opponents remain an eclectic bunch. They recognize their common adversary and will march together to confront him in a common front. But their political motivations are diverse. Bennetts teases these apart with skill.

His narrative, however, rarely strays from Moscow and feels limited as a result. “Discontent may be widespread in the provinces, but it is in the Russian capital that history has always been made,” Bennetts writes. I’ve heard an opposition politician say the same, but I’m not convinced. It’s not uncommon for Russians to say, “There is Moscow, and then there is Russia,” meaning the capital is an isolated bubble. What happens there is not the whole story. Putin can afford to lose large swaths of support in Moscow. When Russians elsewhere move against him, he’ll be in bigger trouble.

Michael Petrou