The composition of a composer: Philip Glass looks back

The new memoir from Glenn Gould Prize winner Philip Glass knits together his pilgrim narratives

Share

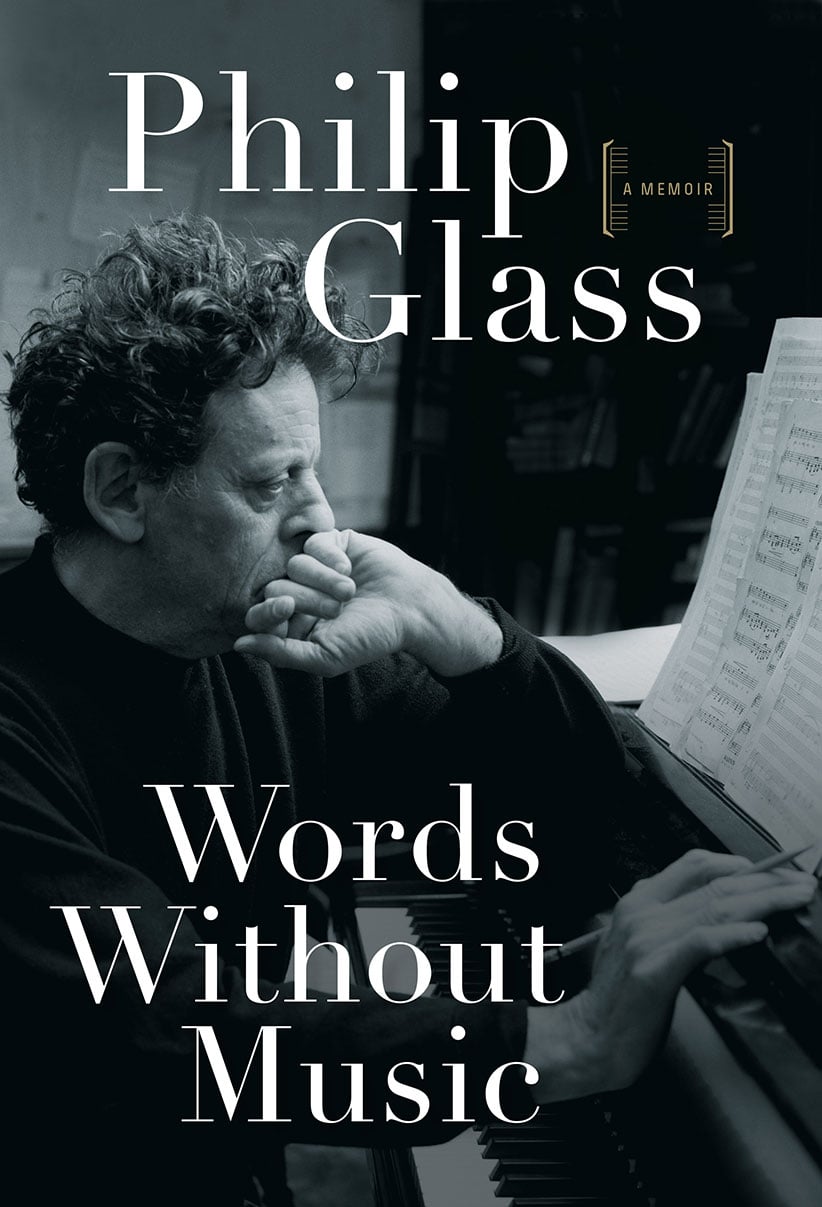

WORDS WITHOUT MUSIC

Philip Glass

Philip Glass’s music has been in everything. From the stage of the Metropolitan Opera to Sesame Street, from Academy Award-nominated film scores to a four-second, two-note alarm for a Swatch, Glass has produced a vast body of work—an oeuvre that just won him the $100,000 Glenn Gould Prize. Add to this his memoir, Words Without Music, which can occasionally read like a record of his profound work ethic. Whether he is writing an opera or recounting his experience as a plumber in New York’s East Village, his time as a taxi driver in Travis Bickle’s Manhattan, or running a moving company, Glass displays a profound respect for work itself, for the way things get done.

But this is no journeyman’s tale. The book is sometimes breezy, sometimes funny and often profound. Glass tells us that his first real motivation to compose came from asking himself a question: Where does music come from?

Unable to find the answer in books, he decided it might be found in writing music. That started a journey that led him from his hometown of Baltimore, through Juilliard and on to Paris to study with one of the 20th century’s most influential pedagogues, Nadia Boulanger. It also led him, in tandem with his spiritual pursuits in India and Nepal, to Ravi Shankar. The duality between the music of Shankar and the Western teachings of Boulanger forms the core of Glass’s future pursuits in music, and his quest to answer the elusive question that set him on his odyssey of sound.

With Boulanger in the early 1960s, Glass honed the intense discipline that would provide the foundation for the towers of sound he would build in the following decade. Their relationship, and his studies with her, are given a full chapter, and their Whiplash-esque dynamic is full of surprising moments of tenderness.

This is preceded by a chapter dedicated to Shankar, in which Glass expounds on a moment that is iconic in Glass lore: Unable to transcribe the rhythms of Shankar’s music, Glass was told that “all the notes are equal.” For musicians and non-musicians alike, this idea takes a moment to sink in. But Glass is so able to translate complex musical ideas into everyday language, the act that followed (erasing the bar lines, the superstructure of Western music) is understood as more than a metaphor.

Most music memoirs and biographies attempt in some way to answer the question that set Glass before those blank staves of notation paper. Most flounder and fail. Words Without Music is part travelogue, part portraiture, part funny anecdote and part spiritual journey. It owes much to the pilgrim narratives that inspired Glass to visit Nepal—where a person relates not just the wisdom he was seeking, but the mechanics of how it was sought. Glass, in a section of the book that describes his spiritual quests, reminds us that no matter how many books you read, wisdom comes from direct interaction with a master. Glass doesn’t succeed in answering his question, and he revels in it. Listen to the music. It comes from Philip Glass.