The fertile poverty of Toronto’s first immigrant neighbourhood

An ode to the erased ward of St. John’s, which once repelled and fascinated early Torontonians

No caption.

Share

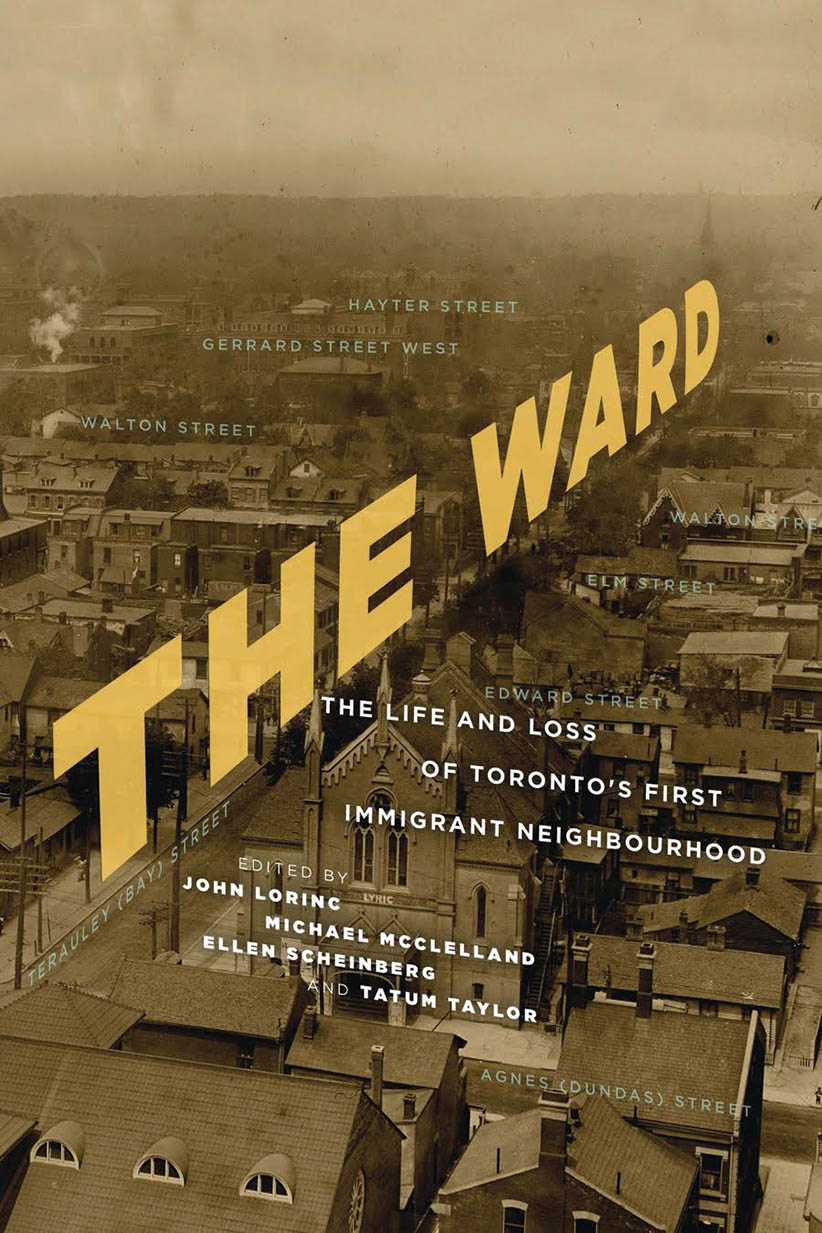

THE WARD: THE LIFE AND LOSS OF TORONTO’S FIRST IMMIGRANT NEIGHBOURHOOD

Edited by John Lorinc et al.

To arrive in Toronto, and to arrive poor, in the decades before the Great War—when the city’s population ballooned from 56,000 in 1871 to 376,000 in 1911—almost always meant arriving in St. John’s ward. Stretching over a large chunk of what is now Toronto’s central core—between Queen and College Streets, Yonge and University—the ward had always housed many of the city’s first outsiders: Catholic Irish and black Canadians. Now they were joined by new waves of non-traditional immigrants: Jews, other eastern Europeans, Italians and Chinese.

The 50-odd short pieces in The Ward—a mixed collection of memoir, archival research and micro-history—bring it back to vivid, impressionistic life. Crammed into cheap lodgings, subject to an appalling sanitation system and often desperately poor, the inhabitants were nonetheless remarkably entrepreneurial. All kinds of businesses flourished in the neighbourhood, legal and illegal: The ward was ground zero for bootlegging during Ontario’s flirtation with prohibition from 1916 to 1927. Contributors to The Ward explore the rag trade, the sex trade, Chinese laundries and paper boys. The outspoken former city councillor Howard Moscoe provides “My Grandmother the Bootlegger”; gallerist Stephen Bulger writes on Arthur Goss, Toronto’s first official photographer—in an era where there was such a thing—whose photos became source material for Michael Ondaatje’s In the Skin of a Lion. There are entries on the Eaton’s strike of 1912, the drive to eradicate tuberculosis, and monumental avenues never constructed. Writers pore over old maps and try to reimagine what once was.

It requires imagination, because the ward—which both attracted and repelled the surrounding city, still British and prone to bouts of puritanical xenophobia—was almost entirely erased from existence and memory. By the 1960s, parking lots, car dealerships and the expanding public sector—city halls, old and new, law courts and some of Canada’s leading hospitals—stood in its place. Sunk deep in the city’s DNA is its willingness to erase its past, its natural features and anything else that might impede the free flow of commerce. The most important achievement of The Ward is to remind Torontonians—who are wrestling, in their globalized city, with issues that seem unchanged—that St. John’s once existed.