The man who invented rock ’n’ roll

The story of Sam Phillips and his mission to change the world

No caption.

Share

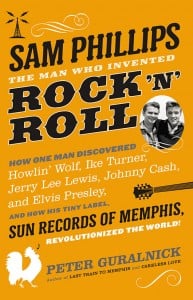

SAM PHILLIPS THE MAN WHO INVENTED ROCK’N’ROLL

Peter Guralnick

If you know who Sam Phillips is, you know he discovered Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison and more, recording them at the tiny Memphis storefront he opened in 1949. You may know that, in 1951, he also recorded what’s considered to be the first rock ’n’ roll single, Rocket 88, featuring a distorted guitar sound doubled with a saxophone, and Ike Turner on piano—recommended to him by another client, B.B. King.

But Phillips wasn’t just there to press the “record” button: He was on a mission to change the world. He fervently believed music could upend racial and class structures. He didn’t want perfect players and singers; he wanted people whose imperfections made them unique. (In 1941, he formed his first group, with players from his high school marching band. He told them, “If you’re going to hit a wrong note, hit it like you mean it!”) He recorded street buskers, bluesmen, hillbillies, prisoners, and a man who played harmonica hands-free, the entire instrument in his mouth. When he didn’t think the big record labels were paying proper attention, he started his own, Sun Records, and, to his dying days, he raged against corporate control of music.

The story of Sam Phillips is not just a musical journey; it’s a portrait of a polymath, an incredibly driven Southern eccentric. Phillips was never short of novel business ideas; he launched the country’s first radio station with an all-female DJ staff, WHER. He addressed the first meeting of a group of indie record execs by telling them they were all “a sorry bunch of bastards,” and that “we’re going to have to act like something other than crooks.” He suffered from anxiety attacks and had electroshock therapy. His long-suffering wife tolerated his many extramarital dalliances, including one that lasted almost 50 years, until his death. He was prickly and combative with his beloved sons. When Elvis fans came to him expecting hagiographic tales, he delighted in horrifying them with a graphic story about their idol’s genitalia.

Guralnick knows Phillips’s world well: He wrote a definitive biography of Elvis, as well as iconic books about country music (Lost Highway) and R&B (Sweet Soul Music). He clearly delights in telling Phillips’s tale. Guralnick is known for being an excellent and empathetic biographer: straightforward, never florid. The first 455 pages of this 661-page book follow that formula. Then we get to 1979, when Guralnick begins a personal relationship with Phillips and his family. Forty pages before the end of this tome, in the middle of a lengthy denouement, the author comes uncharacteristically clean. “Hell, why not just come out and say it? I loved Sam.” By that point, so do we.