The real life of Egypt’s most important female pharaoh

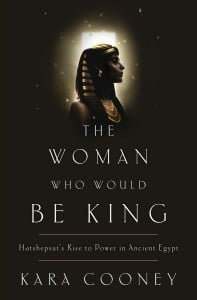

Book review: Kara Cooney’s ‘The Woman Who Would Be King’

Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple rises against a desert bluff. (Kenneth Garrett/Getty Images)

Share

THE WOMAN WHO WOULD BE KING: HATSHEPSUT’S RISE TO POWER IN ANCIENT EGYPT

THE WOMAN WHO WOULD BE KING: HATSHEPSUT’S RISE TO POWER IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Kara Cooney

The story of Hatshepsut, the second and most important woman to become pharaoh in ancient Egypt, unfolds along two tracks. There is her own successful reign, and there is her controversial afterlife. What Western scholars, in a fashion that reliably reflects our own evolving gender politics, have made of Hatshepsut is as fascinating as her own life.

Born about 1508 BCE, the daughter of Pharaoh Thutmose I and his primary spouse, “King’s Great Wife” Ahmes, Hatshepsut was destined to marry one of her own brothers, but both of Ahmes’s boys predeceased their father, and she ended up as Great Wife to a half-brother, Thutmose II, son of a lesser wife. When he died young, leaving a handful of toddler sons—none of whom were Hatshepsut’s—the dynastic succession was in play.

By then, Hatshepsut was already at the apex of accepted female power: not only Great Wife, but the most important priestess in the kingdom, with close ties to a religious power structure almost as influential in politics as the papacy was in a medieval European state. If the future Thutmose III had been her own son, she would have become regent, as numerous royal mothers had before her. As it was, she took that position, brushing aside any claims made for the boy’s low-born mother. But that was only a minor hiccup in royal politics: When, a few years later, Hatshepsut declared herself pharaoh, it was a revolution.

Previous generations of Egyptologists have seen a Cleopatra-like saga of sexual intrigue and unnatural ambition, a situation that an aggrieved Thutmose III responded to by defacing her many impressive monuments. Cooney offers a far cooler and, ultimately, convincing explanation that turns on just how revolutionary a political system based on maintaining the status quo can be. Hatshepsut’s high lineage could be seen as trumping her sex: Both her half-brother-husband and stepson-nephew were children of lesser women; the father was sickly and died young, so the same fate might befall the boy. Pondering all this, the Egyptian elite might well have asked: What chaos are we risking? Far better to forget Hatshepsut was a woman and remember she was both high-born and capable—a realization that required almost two centuries’ worth of consideration among Western scholars.