The Staples Singers on a Mission

A review of Greg Kot’s biography on gospel singer Mavis Staples

Share

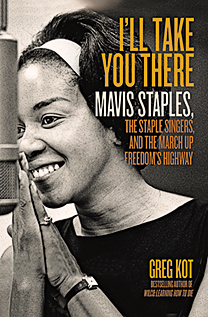

I’ll Take You There: Mavis Staples, the Staple Singers and the March Up Freedom’s Highway

By Greg Kot

When Mavis Staples ?rst started performing gospel music in public with her family, at age eight, she didn’t understand why people were crying when they heard her sing; she thought she was hurting them somehow. She soon realized she was healing them, a mission she’s still on today. Led by her father, Roebuck “Pops” Staples, Mavis and the Staple Singers sold millions of records as a gospel act for 15 years before they scored a No. 1 pop hit in 1971 with I’ll Take You There. They appeared frequently at key rallies with Martin Luther King Jr. in the deep South. (“If he can preach it, we can sing it,” Pops told his family.) Aretha Franklin and Sam Cooke were close family friends; Mahalia Jackson was a neighbour. Bob Dylan asked Pops for Mavis’s hand in marriage. They turned down an opening slot on a Rolling Stones tour because they found the money insulting. When they consciously crossed over to the pop world—prompting one pompous, white British music critic to write that they were “Uncle Tomming for the ?ower children”—the Staples insisted on always singing inspirational songs relevant to the civil rights era, regardless of whether or not God was mentioned in the lyrics. Respect Yourself, their second-biggest hit, had a line exhorting white America to “take the sheet off your face, boy / It’s a brand-new day.”

Though Mavis was, and is, the star of the show—she’s still touring and recording some of the most vital music of her career—she’s a secondary character in her own biography. Pops, born on a Mississippi plantation and the grandson of a slave, was witness to all the sweeping social and musical changes of 20th-century African-American history. The teenage Pops and his bride moved to Chicago, where he worked factories and stockyards, never considering a musical career until he and his children started getting offers from neighbouring churches.

Chicago journalist Kot was given access to Pops’s unreleased memoir, and interviews plenty of key Staples collaborators—even the notoriously reclusive Prince, who wrote and produced two records for Mavis. With subject matter like this, Kot’s job seems almost effortless, but he has a keen ear for musical detail, and the concise prose of a daily newspaper writer. “We don’t teach enough black history in the schools,” says Mavis. “But I’m the history. I’ll be the history. The kids need to know.”

Michael Barclay

Visit the Maclean’s Bookmarked blog for news and reviews on all things literary.