The story behind the novel Dr. Zhivago

Russian poet Boris Pasternak’s laughed off criticisms of his epic love story: ‘I just grin’

Share

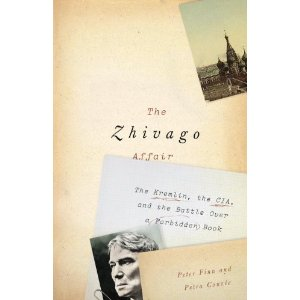

THE ZHIVAGO AFFAIR: THE KREMLIN, THE CIA, AND THE BATTLE OVER A FORBIDDEN BOOK

Peter Finn and Petra Couvée

The story starts when Russian poet Boris Pasternak disobeyed Soviet authorities and let an Italian businessman publish his epic love story, Doctor Zhivago. The Soviet Union allowed writers an elevated status, but expected from them fiction that celebrated Communism.

Pasternak would have none of it. To tailor his art to the demands of the state was a sin against his genius, he proclaimed. For 10 years he toiled away at Doctor Zhivago, his one and only novel, but took only hesitant steps toward publication. Pasternak’s neighbour had been executed with a bullet to the head for publishing material that denounced Stalin’s orders as “the castration of art.”

Privately, Pasternak passed around pages of the novel but doubted it would ever reach the public.

Privately, Pasternak passed around pages of the novel but doubted it would ever reach the public.

“When they print it, in 10 months or 50 years, is unknown to me and just as immaterial.” The book might never have seen the light of day if not for the scouting agent of an Italian multimillionaire who implored Pasternak to release it in the West. Handing over the manuscript, Pasternak told the Italian, “You are invited to my execution.”

Doctor Zhivago was published in Milan on Nov. 15, 1957, provoking attacks from notables like Vladimir Nabokov, who panned it as clumsy and trite. Israel’s prime minister slammed it for its view that Jews should assimilate. “Satanically narcissistic” is how a fellow Russian writer described the novel. Pasternak laughed off the criticisms. “I just grin as though this abuse and condemnation were praise.”

In the West, the book had powerful admirers among CIA agents. “This book has great propaganda value” read a memo to all branch chiefs of the CIA Soviet Russian Division. The CIA funded a New York publisher to print thousands of copies, which they gave out for free at the Brussels World Fair. But Pasternak’s real problems began when he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1958.

The Kremlin forced him to refuse the prize or face expulsion from the country. Pasternak died of untreated lung cancer shortly afterwards, leaving a fortune in royalties in a foreign bank account and a widow left to live like a pauper. Years later, Khrushchev lamented in his memoir, “We shouldn’t have banned it. I should have read it myself. There’s nothing anti-Soviet in it.”