The true story of one of Berlin’s vanished Jews

Book review: The long-buried memoir of a Jew who ‘passed’ during WWII

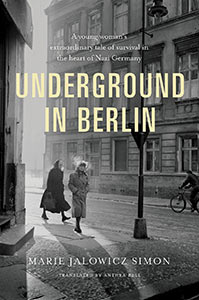

Underground in Berlin by Marie Jalowicz Simon. No Credit.

Share

UNDERGROUND IN BERLIN

Marie Jalowicz Simon

The essence of the Holocaust always has been the personal and heart-wrenching stories of its victims. In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, those who, against all odds, had survived did not speak about their tragic experiences; it was too painful and often too humiliating. That changed in the ensuing decades with the advent of oral history collections, Holocaust museums and the publication of memoirs. Still, some survivors, like Marie Jalowicz Simon, who was 11 years old and living in Berlin with her middle-class Jewish family when Hitler came to power in 1933, refused to tell her own children the remarkable tale of how she had eluded death. Then, one day in 1997, her son, Hermann Simon, a historian, turned on a tape recorder and urged his mother to tell him her story. And, in a candid interview that used 77 tapes and stretched into many months, completed only a few days before her death in 1998, Marie related her incredible ordeal as Jew in hiding in Berlin during the war.

Hermann’s interview with Marie was transformed into a book published in German in 2014 and aptly entitled Untergetaucht (“Submerged”). From mid-1942 on, when Marie, alone following the death of her father in 1941 (her mother had died in 1938), symbolically ripped off her Star of David marking her as a Jew, she was akin to a U-Boat, as the writer and free-speech advocate Lisa Appignansei explains in the book’s introduction. Marie was one of 1,700 vanished Jews in Berlin, who somehow stayed under the acute Nazi radar.

Described here with penetrating insight and frankness, Marie’s survival as a young Jewish woman relied on several factors: enormous courage and daring that tempered the chilling fear that nearly consumed her; the brave and dangerous assistance of many non-Jewish resisters—all described with delicious, novelistic detail—who supplied her with shelter, food and fake identification papers; and sheer luck, which played a part in the survival of many European Jews during the Holocaust. She endured forced labour, encountered indifferent Nazis who ignored her obviously phony identification papers, repeatedly evaded the Gestapo and its numerous spies, lived side-by-side with Nazi sympathizers whom she fooled, and suffered through a self-inflicted miscarriage.

When the war ended, Simon emerged from hiding and, like other survivors, gradually rebuilt her shattered life in what was soon to be East Germany. She married and became a professor. “I would have liked to weep for joy and relief,” she recalled about her liberation, “but I felt no emotion at all.”