The unglamorous plight of a female alcoholic

A blackout drinker’s memoir as cautionary tale

Share

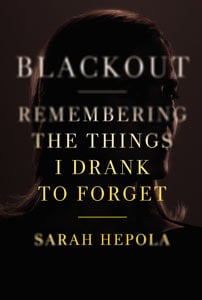

BLACKOUT: REMEMBERING THE THINGS I DRANK TO FORGET

Sarah Hepola

Sarah Hepola gained fame as an American magazine writer and editor, including her turn as Salon‘s personal-essays editor. Now comes her brutally honest memoir, where she’s calling the bluff on the glamour of her once-saucy life. The book follows Hepola from her early childhood in Texas, stealing beer from her parents’ fridge, through to high school parking-lot piss-ups and college ragers—just teen mischief, if the author didn’t make such a case for these being the building blocks of addiction. By the time she reaches her mid-20s, her problem is as obvious to her as it is to her friends, as huge swaths of her life get lost in a terrifying amnesiac abyss. It takes another decade or so, with the help of therapy and AA, to shine a more permanent light on that darkness.

Her account is funny, touching and painful—no doubt set up with the deft and occasionally vainglorious hand of a click-bait pro, but with the soul of something deeper and much more resonant. Through her personal story, Hepola illuminates how the various issues in women’s lives—from body dysmorphia, dieting and celebrity culture, to the pressure of perfect parenting and the work-life “lean in”—are, for some women, mediated, muddied and self-medicated with booze. Especially troubling are the ways in which Hepola links blackouts to rape culture and consent, sure to be one of the more controversial aspects of a controversial book.

In recent years, there has been a spate of non-fiction books examining the relationship between women and alcohol: Drinking: A Love Story; Drink: The Intimate Relationship between Women and Alcohol; Smashed; and Drunk Mom, coming as fast and furious as the booze, with names like “Mommy Juice” and “Skinny Bitch” filling liquor-store shelves. Do we have an epidemic of female alcoholism on our hands? The jury is still out, but if Hepola’s memoir is any indication, the relationship can no longer be ignored. “I looked up to women who drink. My heart belonged to the defiant ones, the cigarette smokers, the pants wearers, the ones who gave the stiff arm to history,” she writes, almost finger-pointing at feminists. But, under her judicious lens, the narrative of the “blotto heroine”—both fictional, as in Carrie Bradshaw and Bridget Jones, and not, as in “Are You There, Vodka? It’s Me, Chelsea” Handler—takes a dark turn. The image of the good-time gal, drinking like the boys, threatens to morph, as the author did, into a bloated, middle-aged woman with debt, a shot liver and a lonely life full of risky sex. It’s a gruesome image, and one Hepola hopes we stop glamourizing, and grow out of, as she did.