Why we miss Christopher Hitchens

Brian Bethune on ‘And Yet,’ a new collection that reminds us of all that was lost four years ago

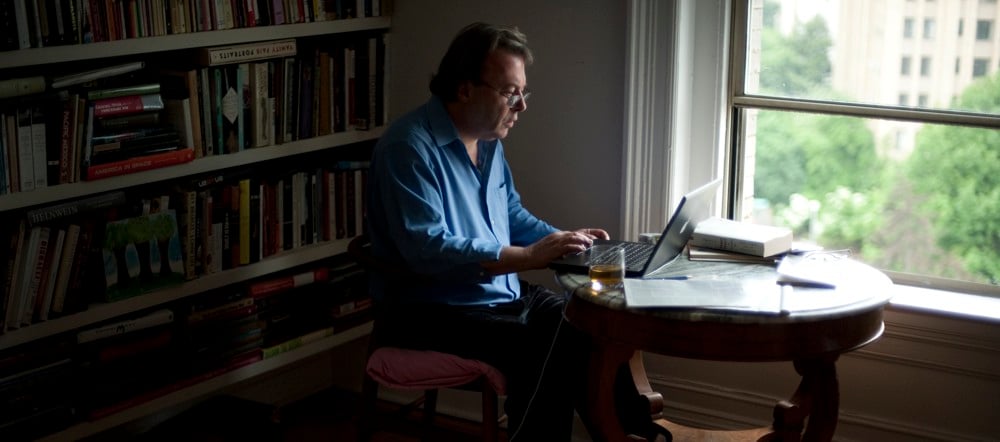

WASHINGTON, DC -MAY 17:

Share

It doesn’t take long reading Christopher Hitchens, even an article on a political issue that’s no longer topical, even an opinion you hate, to realize how much of a void he left at his death four years ago. The chattering classes, whether they realize it or not, miss him like an amputated limb, to adopt his own apt metaphor about his feelings for his youthful Trotskyite follies. It’s the voice, of course, made up of self-confidence that frequently crossed the border of arrogance, erudition—the man’s knowledge of 20th-century literature and political history was extraordinary—literary ability, powerful memory (and not just for slights), omnivorous curiosity, courage and moral truculence.

Related: Noah Richler in conversation with Christopher Hitchens

Like any opinionated and prolific hack, a term he would have embraced—no Johnsonian blockhead, Hitchens wrote to eat—he left a lot of words (250,000) never gathered into book form. The just-released essay collection And Yet… strikes a sweet spot in his remaining oeuvre, between the first-rate pieces still left after the immediately topical essays were rushed into print in the wake of his December 2011 death from esophageal cancer, and not yet those final dregs publishers will eventually be reduced to strip-mining.

It hardly matters what their ostensible topics are, although, for the record, the pieces range from a consideration of Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk through Hitchens’s enduring contempt for both Clintons (for whom he reserves his finest terms of vilification, “squalid mendacity” being merely the most resonant) to a look at Arthur Schlesinger’s memoirs. The last of these is Hitchens in a nutshell. He begins, as any reviewer would, seeking what he could learn about the Kennedy White House, for which Schlesinger functioned as starry-eyed court historian, but quickly moves to an evident fascination with the self-deceptive effects of being a bystander in the halls of power.

Related: Paul Wells: Reading Christopher Hitchens reading

In the process Hitchens comments amusingly on the memoirs’ “disappointing absence of rancor,” compares Schlesinger to a Stendhal character who could never remember if he was at the Battle of Waterloo (just showing off there), notes how the historian—probably unwittingly and certainly unwillingly—portrays a madly improvising and barely in-control presidential administration during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and even manages a good word for LBJ, possibly the only one ever offered him by Hitchens.

It would be a stretch to say this focus was all about Hitchens himself, but it marks an intense self-consciousness about the moral hazards of public commentary and flying too close to the sun, a determination to not be that guy, not a courtier like Schlesinger. After the erudition and wit, what gave Hitchens’ commentary its final, neck-twisting moral effect—at least while the better angels of his nature were ascendant—was the commitment to not ignore the sins of his own tribe and, perhaps harder, pay due tribute to the character of his opponents.

All that came from Hitchens reading of his hero, George Orwell, who figures in two of And Yet’s essays. Hitchens on Orwell reveals what makes Hitchens tick, because he correctly zeroed in on the core of Orwell’s greatness, his ceaseless examination of supposedly self-evident facts, especially facts about himself. An upper-class Englishman raised with an aversion for Jews, a contempt for homosexuals and a disdain for the working class, Orwell persistently questioned his own prejudices. In conscious imitation—albeit with less success, given his robust ego—Hitchens strove to do the same. That as much as anything led him to a host of iconoclastic positions, many of which left him out on a lonely limb, at odds with his erstwhile associates.

In a political climate with echoes of Auden’s low and dishonest era, the void where Hitchens was seems larger than ever. Is there anyone writing now whose commentary on a xenophobic field of Republican presidential aspirants or a rampaging ISIS contains the possibility of surprise or challenge? That’s why we miss him.

Related: Why Hitchens deserves to be remembered with Orwell

(This post has been updated.)