Yet another side of Jackie Kennedy

Barbara Leaming takes on the social and psychological aspects of the iconic Jackie Kennedy’s roller-coaster life

Share

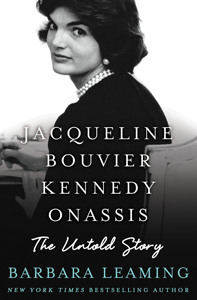

JACQUELINE BOUVIER KENNEDY ONASSIS: THE UNTOLD STORY

JACQUELINE BOUVIER KENNEDY ONASSIS: THE UNTOLD STORY

By Barbara Leaming

With the possible exception of Marilyn Monroe, no 20th-century American woman has been as thoroughly analyzed as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. She has been the subject of hundreds of books, ranging from sensationalist (Kitty Kelley’s trashy Jackie Oh!) to scholarly (Alice Kaplan’s gem-like Dreaming in French). Is, as Leaming promises, anything still untold? Yes, in a sense.

It is the perspective Leaming takes, focusing squarely on the whys of Jackie’s roller-coaster life, the psychological and sociological underpinnings, that makes this lean volume both refreshing and uniquely insightful. Leaming has built a formidable reputation for shaping biographies of outsized figures—Churchill, Monroe, Katharine Hepburn, Orson Welles, plus previous volumes on Jackie and JFK—that are the literary equivalent of a sensible yet stylish shoe or an architecturally striking brick house: solid and dependable, yet masterfully rendered and enticing.

She begins not with Jacqueline Bouvier’s birth but with her prep school and college days in the late 1940s and early ’50s, as a stepdaughter to the mighty Auchincloss dynasty, expected to marry well and disappear into the pages of the social registry. She did marry well, to a Kennedy, no less, for better and worse. Patriarch Joe Kennedy adored and mentored her. Jack loved her in his way (though his philandering remained insatiable as he bedded everyone from secretaries and family friends to Monroe). It was, at least outwardly, a Cinderella story that remained magical until Nov. 22, 1963. Which is where Leaming’s tale gets most interesting.

In the aftermath of JFK’s assassination, prominent men, all well-meaning, including RFK, Robert McNamara, David Ormsby-Gore, Joe Alsop, Ted Sorensen and, later, Aristotle Onassis, sought to shield and protect Jackie. The public ascribed to her superhuman nobility, later turning its back when she proved too human, her marriage to Onassis condemned as both grand-scale gold-digging and a repudiation of her widowhood. All the while, Leaming posits, Jackie was suffering from a condition that hadn’t yet been named or identified: post-traumatic stress disorder. She exhibited all the classic symptoms, including endless recitation of the details of that terrifying day and an intense terror of history repeating itself. (She envisaged herself a potential victim—a fear significantly compounded by Robert’s murder in 1968.)

Not until the late 1970s, after Onassis’s death, was she finally able to shake off the past and fully take charge of her destiny, toiling as a book editor in New York, championing historic preservation projects and establishing a private haven on Martha’s Vineyard (admittedly, thanks to a hard-won $26-million settlement from her second husband’s estate). There, toward the end of her story, she tells her only son that if JFK were to walk through the garden at that moment, she’s not sure she’d want him back. Faun-like Jackie, whose life and iconography had been largely shaped and defined by powerful men, was at last her own woman.