Claude Monet and his Water Lilies

Ross King delivers a moving biography of Claude Monet and an engrossing depiction of the Great War era

Share

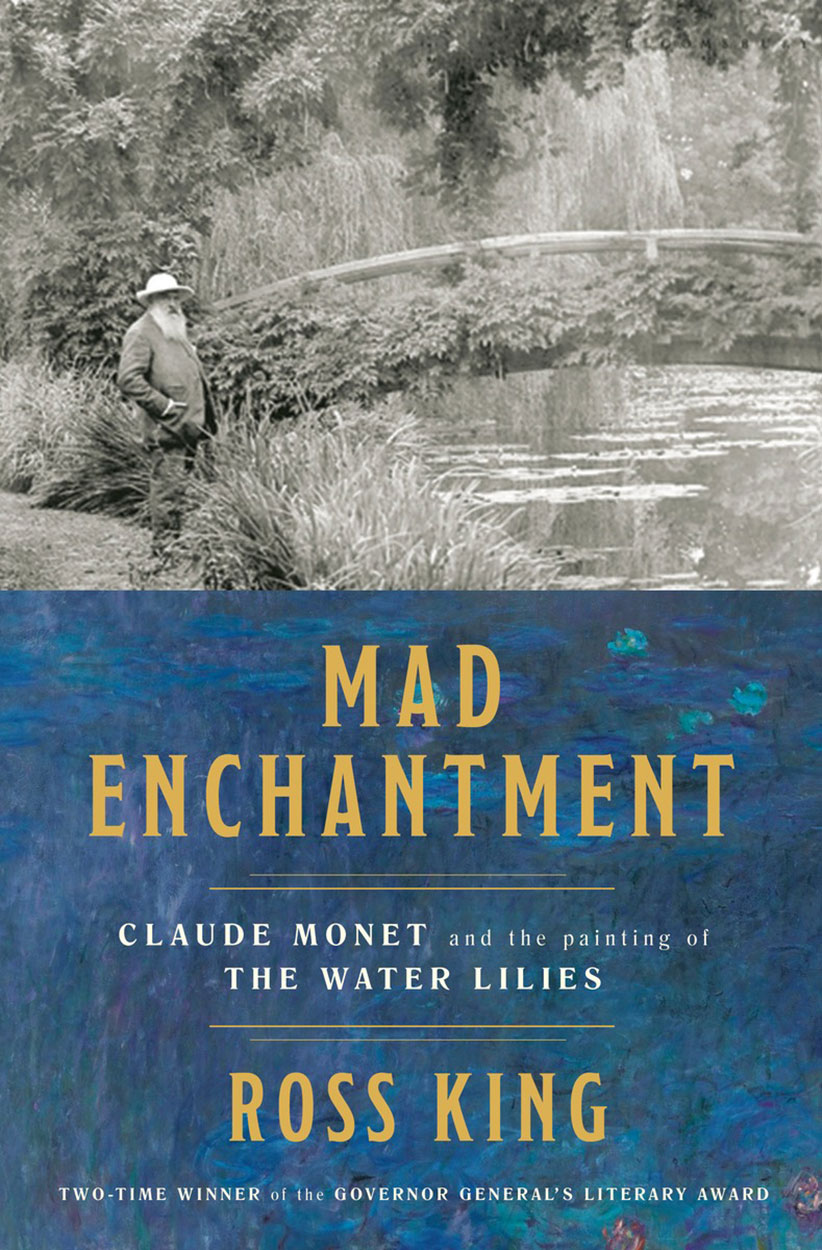

MAD ENCHANTMENT

By Ross King

This book, subtitled Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies, deserves a place of pride beside Margaret MacMillan’s Paris 1919 for its engrossing depiction of the Great War era. Canadian author Ross King, a two-time winner of Governor General’s awards for non-fiction, gives us another moving biography of an artist at the centre of a city’s cultural and political upheavals.

This time, that artist is impressionist master Claude Monet. The city is Paris—well, actually it’s Giverny, a small village about 74 km to the northwest. When the widower Monet arrived there in 1883, he brought with him two sons, his mistress, Alice, and her six children. Three decades later, he was an acclaimed artist with a collection of motorcars and the lordly habit of painting in a tweed suit. Every year, he spent a small fortune on his garden, which became the sole subject of his art and a national curiosity.

Everything fell apart when Alice died in 1911 and Monet began to go blind. He stopped painting. The horrors and privations of the First World War soon raged, sometimes within earshot of Giverny. The only person who could cajole Monet back to work was his longtime friend Georges Clémenceau, the politician and war hero. This book is as much a chronicle of their touching friendship as it is the story of the painting of the water lilies. Clémenceau’s patience with crotchety old Monet was legendary, as was his ability to cajole Monet to finishing the series of enormous watery canvases known as the Grande Décoration.

With impressive deft, King weaves into his narrative the story of the rise, fall, then rise again of Impressionism’s reputation, as well as the fate of the Orangerie, the final resting place of Monet’s Grande Décoration in Paris. Along the way, Monet destroyed more than 500 canvases in fits of rage and perfectionism.

King takes us on that journey with often funny asides (“Monet without a regular supply of cigarettes did not bear contemplation”) and withering comments about the French government’s “too little, too late” acceptance of Monet as a cultural hero.