Defending the grunt

From 2009: Purists hate it, but what’s a guttural outburst (or several) in a great tennis game?

Share

When Serena Williams stopped by The Late Show last month after winning a third Wimbledon title, the conversation, like many about tennis these days, turned to grunting rather than groundstrokes. Williams joked that she grunts playing golf and said Monica Seles, tennis’s first scream queen, was her role model growing up. When David Letterman asked if her outbursts distracted opponents, she smiled: “I often wonder that.”

Though the bit went over well with the studio audience, it’s unlikely everyone at home was laughing. Grunting has become a divisive issue in tennis, especially in the women’s game. Purists complain the guttural outbursts are unnecessary and annoying to spectators and opponents. Martina Navratilova recently called it “cheating” and said it should be outlawed.

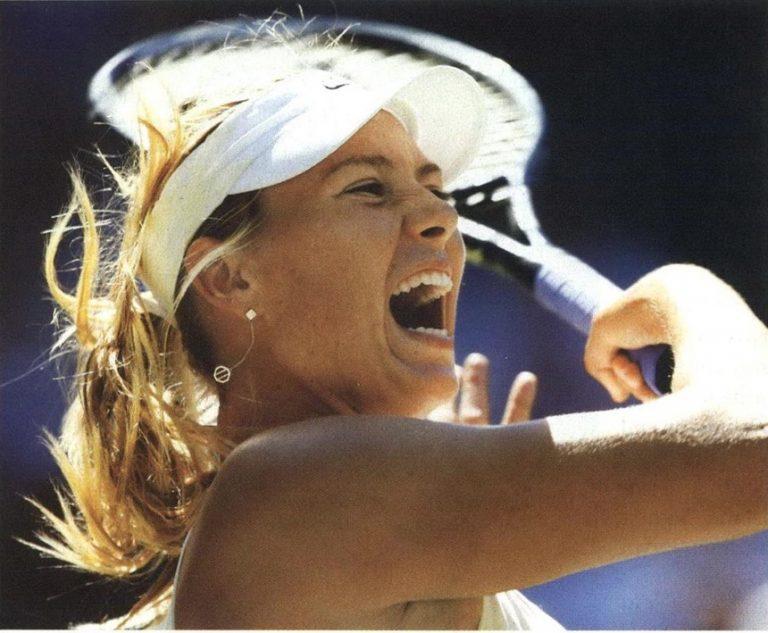

The battle’s next round may unfold at the Rogers Cup in Montreal and Toronto this month, but the issue isn’t a new one. The legendary Jimmy Connors was grunting to victory long before Seles inspired the grunt-o-meter in the ’90s and Maria Sharapova measured 101.2 decibels (almost as loud as a police siren) in 2005. The debate resurfaced a couple of months ago after the, um, racket made by Michelle Larcher de Brito at the French Open. Soon after the 16-year-old’s shrieking made headlines, the International Tennis Federation was said to be considering a rule to curtail grunting in the sport.

The main offenders claim grunting isn’t a tactic aimed at psyching out opponents—it’s just how they’ve always played. Some suggest it helps with the timing of shots. Others say it’s a product of the modern game, which is, obvious to anyone who has seen Williams’s thighs, all about power. Tennis is more “explosive” now, compared with a couple of decades ago, says Martin Laurendeau, Canada’s Davis Cup captain and men’s national coach. “Any sport that you need to load that sort of energy into a fraction of a second,” he says, “you have to expect something to come out.”

Some players are just louder than others. While Roger Federer, arguably the greatest player to ever lace up a pair of tennis shoes, is a silent assassin on the court, Rafael Nadal, currently No. 2, makes a lot more noise to get things done. There’s nothing wrong with that, says Ross Flowers, a sports psychologist with the U.S. Olympic Committee, who argues athletes shouldn’t bottle their emotions. “The grunt allows athletes to express themselves—release the power they’re putting into each play,” he says. “Restricting that is restricting the game.” When Seles was told to turn the volume down in her Wimbledon final against Steffi Graf in 1992, she was soundly—or rather silently—defeated.

And now comes scientific evidence that grunting improves performance. A recent study of U.S. college players found that those who don’t typically grunt increased the speed of both serves and forehands by about four miles an hour by grunting. In a radio interview last month, Dennis O’Connell, the author of the study and a professor of physical therapy at Hardin-Simmons University in Texas, said “grunting can serve a purpose any time anyone is asked to do a maximal exertion.”

One big complaint among critics, however, is that some pros exaggerate their grunts to mask the sound of the ball off their racquet, used to gauge an opponent’s return. Rene Simpson, Canada’s Fed Cup captain and a grunter during her pro days, doesn’t buy it. “You’d have to have incredible timing,” she says. She doubts coaches are training players to use it as a psychological tool: “I don’t know any coaches who say, ‘Okay, scream every time you hit the ball to throw your opponent off.’ ” She thinks it has more to do with breathing, a point echoed by Nick Bollettieri, the coach of Andre Agassi, Sharapova and Seles, whom some blame for the rise of grunting. Bollettieri claims he teaches players how to breathe, not grunt.

In the end, says Simpson, “half of the world’s best players grunt.” Stopping it, she says, throws off breathing. “That doesn’t allow for a loose stroke. It causes tension and will affect play.” Laurendeau lacks sympathy for players who can’t handle the noise. “If you’re on Centre Court, you have to be ready for distractions—bad calls, gusty winds, a baby crying or an opponent grunting louder than the norm,” he says. “If an athlete is bitching about an opponent screaming they need to check their concentration skills.” For spectators, he has a simple question: “Do fans prefer lesser performances and less grunting?” If not, there are always earplugs.