Five curious ways popes have left their mark on Rome

Papal fingerprints are everywhere, if you know where to look

Share

The Eternal City is chock full of the Western world’s most important treasures, thanks in large part to the Catholic church’s 266 popes, who collected and commissioned masterpieces, commanded beautifying building projects and acquired art–sometimes through not-so-holy means.

The papal facelifts started nearly from the get-go: The Middle Ages left Roman ruins plundered and used as pastureland. But Pope Martin V began a restoration of the city as early as AD 140; When Pope Boniface VIII proclaimed the first jubilee in 1300, thousands of pilgrims visited Rome thereby lining the papal coffers with plenty of project funding; Nicholas V began building works at both St. Peter’s and the Vatican, where he transferred his residence from the Lateran Palace and tried to slow down the plundering of ancient buildings, which despite his efforts continued well into the 16th century. But it was a member of the influencial Della Rovere family who really got the ball rolling: In 1471 Pope Sixtus IV founded the oldest public collection of art in the world when he donated his sculpture collection to the city, the nucleus of which can still be seen at the Capitoline Museum. (He also rebuilt a chapel you may have heard of that still bears his name.) Another Della Rovere family member–Pope Julius II–continued the beautifation of that chapel when he pulled Michelangelo away (kicking and screaming) from working on Julius’s own tomb. In fact, Pope Julius II made Rome the centre of the High Renaissance, by luring the likes of not only Michelangelo but also Raphael and the architect Bramante, to work on papal projects in Rome.

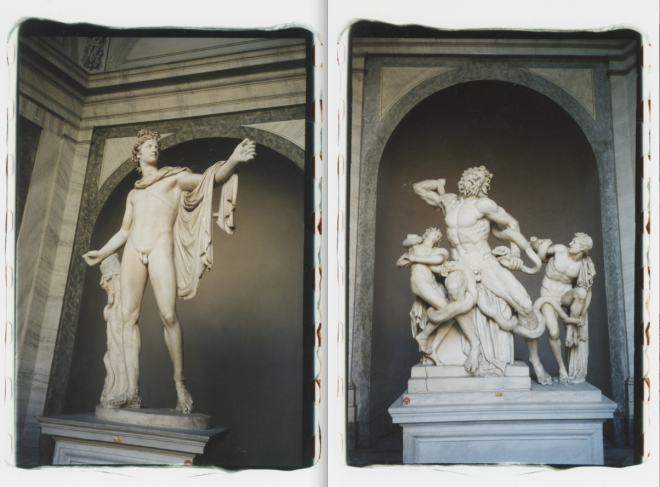

Julius was mad for ancient sculpture, which seemed to be turning up in everybody’s back yard during the 16th century, and he displayed his impressive collection–think The Laocoön and the Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican’s Belvedere Pavillion–helping to make the Vatican Palace home to the largest collection of ancient scultpures in the world. After a little blip during Pope Clement VII’s reign–when Rome was sacked in 1527 by German mercenary trooos–Rome’s population fell to around 30,000 inhabitants. But Pope Sixtus V, perhaps more than any other pope, came back will full pistons firing (St. Peter’s dome was completed under his watch.) And under Paul V’s eyes, the basilica was completed. Popes Urban VIII, Innocent X and Alexander VII turned Rome into the Baroque wonder that is today–think Bernini’s colonnade out front of St. Peter’s and practically every single fountain in the city’s piazzas. And while Scipione Borghese–a major patron of the arts during the 17th century–may have only been a Cardinal, his uncle was Pope Paul V. And he put his art-loving nephew in charge of the papal funds, which conveniently often ended up funding one of the largest and most impressive art collections in Europe. Paul V even went so far as to facilitate the theft of an alterpiece from Peruglia–Raphael’s Deposition, whish still hangs, along with early Caravaggios and nearly every single early marble freestanding sculpture by Bernini, in the Scipione’s Villa Borghese today.

But mapping out what treasures are where in Rome is no easy feat: For starters, antiquities have been plundered, refashioned, melted down and destroyed for centuries (three hundred tons of iron clamps once held the Colosseum’s 100,000 cubic metres of traverstene stone together but after centuries of iron looting, the stadium resembles a piece of Swiss cheese.) And as early as the reign of Emperor Constantine in the 4th century AD, antiquities were mish-mashed together creating collages of art comprised of different styles from various centuries (Think the Arch of Constantine.) There are books dedicated to detailing the minutea of it all, the exterior columns on the Pantheon, for example, come courtesy from both Baths of Nero and Domitian’s villa. But here are five off-the-beaten-track gems that you may have walked by, or on, and never realized that their unusual origins are covered in papal fingerprints.

1. Pope Urban VIII commissioned Bernini to craft an elaborate canopy, or baldachin, over the burial site of St. Peter himself inside St. Peter’s. But the structure, whose columns rise 20 metres, required a lot of bronze. Legend has it that Urban gave the green light to take it from the portico ceiling of the Pantheon. So, in 1626, 200 tons of bronze were melted down to make not only the baldachin but 80 cannons for Castel Sant’Angelo (Hadrian’s mausoleum.)

2. You know how some tourists can get a little persnickety outside the Baptistery in Florence where Brunelleschi’s famed bronze ‘Gates of Paradise’ hang when they remind art-adoring bystanders that the doors are reproductions? Well, same goes for the bronze doors on the facade of the Senate House in the Roman Forum. To see the real deal, make your way to San Giovanni in Laterno, the official cathedral not just of the city of Rome but also of the world. (St. Peter’s, although arguably the most grand and imposing church in Christendom, is not actually a cathedral.) The basilica, first built in the 4th century A.D. on Constantine’s orders over the site of his rival Maxentius’s army barracks–how’s that for not-so-passive-aggressive?–has been sacked, burned down, rebuilt and burned down again. But the impressive (re: enormous) set of bronze doors located under the portico are a couple thousand years old. In 1660, Pope Alexander VII decided that they’d be better suited to Rome’s first basilica rather than collecting dust in the Roman Forum.

3. Next time you’re in St. Peter’s, make a pit stop at the very start of the long nave. Then look down. You’ll see a somewhat ubiquitous-looking round piece of purple marble. Well guess who knelt down on it and was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III on Christmas day in 800 AD? Just Charlemagne, THE GUY THAT STARTED THE CAROLINGIAN RENAISSANCE AND BASICALLY UNITED ALL OF EUROPE FOR THE FIRST TIME SINCE THE ROMAN EMPIREl. It’s a small piece of memorabilia that survived from the original basilica, built on Constantine’s orders in the 4th century AD over top of St. Peter’s tomb, that made its way into Baroque basilica that stands today.

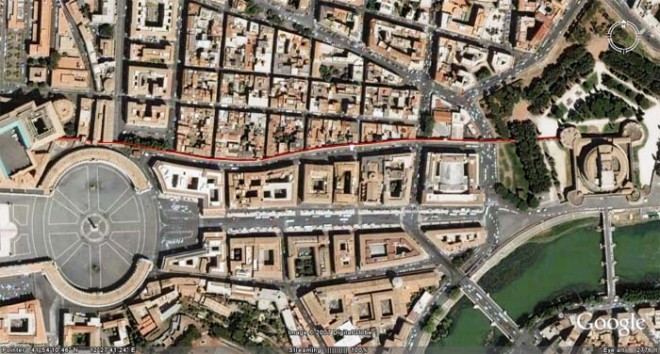

4. There’s a visible passageway, or passetto, that runs on top of the old 9th century AD Vatican wall that connects Vatican City with the Castel Sant’Angelo, an impressive circular structure that started off as Emperor Hadrian’s family mausoleum in AD 139. (It’s also been a citadel, prison, fortress, castle and now, a museum.) The 800-metre fortified corridor, built in 1277 by Pope Nicholas III, allowed Pope Clement VII to escape from the Vatican to the Castel Sant’Angelo during the Sack of Rome in 1527. He took with him some 1,000 followers, including 18 bishops and 13 cardinals, to escape the mercenary troops of Charles V. As H.V. Morton recounts it in his 1957 A Traveller in Rome, “Clement VII, appalled by the fate his politics had brought upon Rome, was on his knees in St. Peter’s. At first he was resolved to dress in full pontificals and meet the enemy seated upon his throne, as Boniface VIII had waited for Sciarra Colonna two hundred years before: but as the cut-throats broke into the Hospital of S. Spirito, slaying all the patients to spread terror, and the cries of the dying and the explosion of cannon were heard on the very steps of St. Peter’s, the Pope was persuaded to take flight along the covered corridor to S. Angelo. ‘Had he stayed long enough to say three creeds,’ wrote an eyewitness, ‘he would have been taken.'”

5. Chances of any bronze artifact, let alone a bronze equestrian statue of an emperor, surviving the passage of time (and countless sacks and invasions) are slim. The Christians melted down any pagan-looking relic they could get their hands on. That’s what makes the very existence of the bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius located in the Capitoline Museum (a replica stands in the piazza, designed by Michelangelo, out front) all the more mind-boggling. It was spared because of a case of mistaken identity: everybody thought it was Constantine, the first emperor to convert to Christianity, albeit on his death bed. It is the only fully surviving bronze statue of a pre-Christian Roman emperor. The nearly two-thousand-year-old massive monument was most likely found on the Lateran Hill in AD 783 but wasn’t brought to the Capitoline Hill until Pope Paul III ordered it to happen in 1538.