Todd McLellan and the art of falling apart

How the Canadian photographer’s assemblies of mechanical objects are catching on

Todd McLellan Motion/Stills Inc.

Share

Underneath the surface of all mechanical things—typewriters, flip clocks, crouching telephones preparing to ring—lies a hidden world of rivets, wires and coiled springs. All his life Todd McLellan has had to placate an urge to uncover these mysterious bits and pieces. When still a child in Saskatoon he disassembled an old stereo his father brought home, tearing it up into its constituent parts. His compulsion just made sense: dad was a carpenter, his mother a technician with Northern Telecom. A few years ago McLellan, now a Toronto-based commercial photographer, got hold of an old rotary phone and, after leaving it plugged into his wall for a few months, took it to his studio with a mind to shooting it. Try as he might, and despite his passion for its sturdy, handsome design, its beauty remained elusive. So he ripped it apart, laid it out like a frog’s dissected body, then dropped its guts from the ceiling. The resulting photographs—innards arrested in midair or spread, with a serial killer’s logic, beneath the lens—are making McLellan famous.

He’s not an art geek. Working out of an old laundromat in Toronto’s Leslieville district as part of Sugino Studio, a commercial photography firm, McLellan, 35, specializes in shooting cars, and spends hours ricocheting light across sleek auto bodies, igniting a shimmering, otherworldly glow inside deep charcoal shadow. Trained at the Alberta College of Art and Design, in Calgary, he still cultivates a functional Prairie haircut; a bobblehead doll likeness, one of a phalanx of such dolls produced by Whoopass Enterprises for Sugino’s principals and displayed in the lobby, depicts McLellan naked save for a strategically placed white cowboy hat and a beer in his hand. But starting with that phone in 2009 he embarked on an exploration of the internal world of things—a venture that’s paid off in strangely career-enhancing ways.

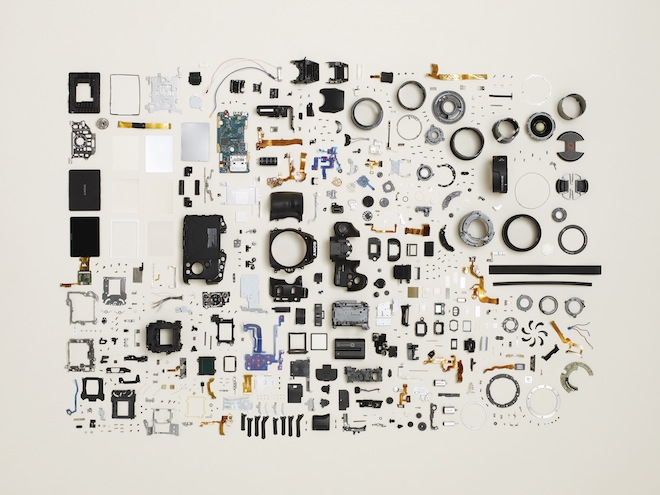

McLellan has dismantled an old Pentax camera, a push mower, a chainsaw, a toaster and a Macintosh computer, among other things, his work desk a jumble of pliers, screwdrivers and heat guns. There’s a performative aspect to the work, and the disassembly—documented in time-lapse footage—is part of what makes the results fascinating: one wonders how he managed to work apart the blades and rivets of that Swiss Army Knife, say. Once, as he pried open a 1928 mantle clock, an inner spring shot up and unspooled like silver lightning, “slicing my thumb about 20 times before I even thought about it, it happened so fast,” says McLellan, a quietly alert man with grey eyes and red hair. “I try to take things apart as much as I can without destroying them. I stay away from that.”

Using flawless leg-bone-connected-to-your-knee-bone logic, he arranges these parts on a blank platform, sometimes taking hours to achieve a harmonious composition, the screws positioned like musical notation in the margins. Cranking an old Hasselblad camera high up on a crane over the disembowelled artifact, he captures swirling patterns of industrial design, morphing the mundane into enchanting assemblage. Then he sends someone up a ladder, the parts expertly prepared for a choreographed spill. “Some pieces fall faster than others,” he says. As they tumble, quick, intense bursts of flash inundate the field, saturating the column with brilliance at just the moment a super-fast shutter yawns in the camera. The effect is crystalline. When McLellan, using Photoshop, collates several such cascades into a seamless picture, the illusion is of an explosion so meticulously calibrated that the bits continue working together mid-blast.

Whether because of the retro objects or the oddness of seeing a piano burst wide, the images caught on. A book, Things Come Apart, got its launch at British designer Paul Smith’s shop in Milan in April, part of the Salone Del Mobile furniture fair. His prints sell out—writers like the typewriter—and the Wall Street Journal wants him as a contributor. “It’s the last thing I was aiming for,” says McLellan, who saw the series as a comment on the ruggedness of old design and on consumerism, and says of that old typewriter before its dismembering: “It still worked—the same way it worked on Day 1.”

Disassembled CompassV2

Apart CompassV2

Apart iPod

Apart Digital Camera V2

Apart Toaster V2

Disassembled iPod V02

Disassembled Toaster V2

Disassembly DigCameraV03