Ian McEwan’s latest novel, as told by a fetus

Nutshell requires a leap of faith, and delivers a ripping good time

Share

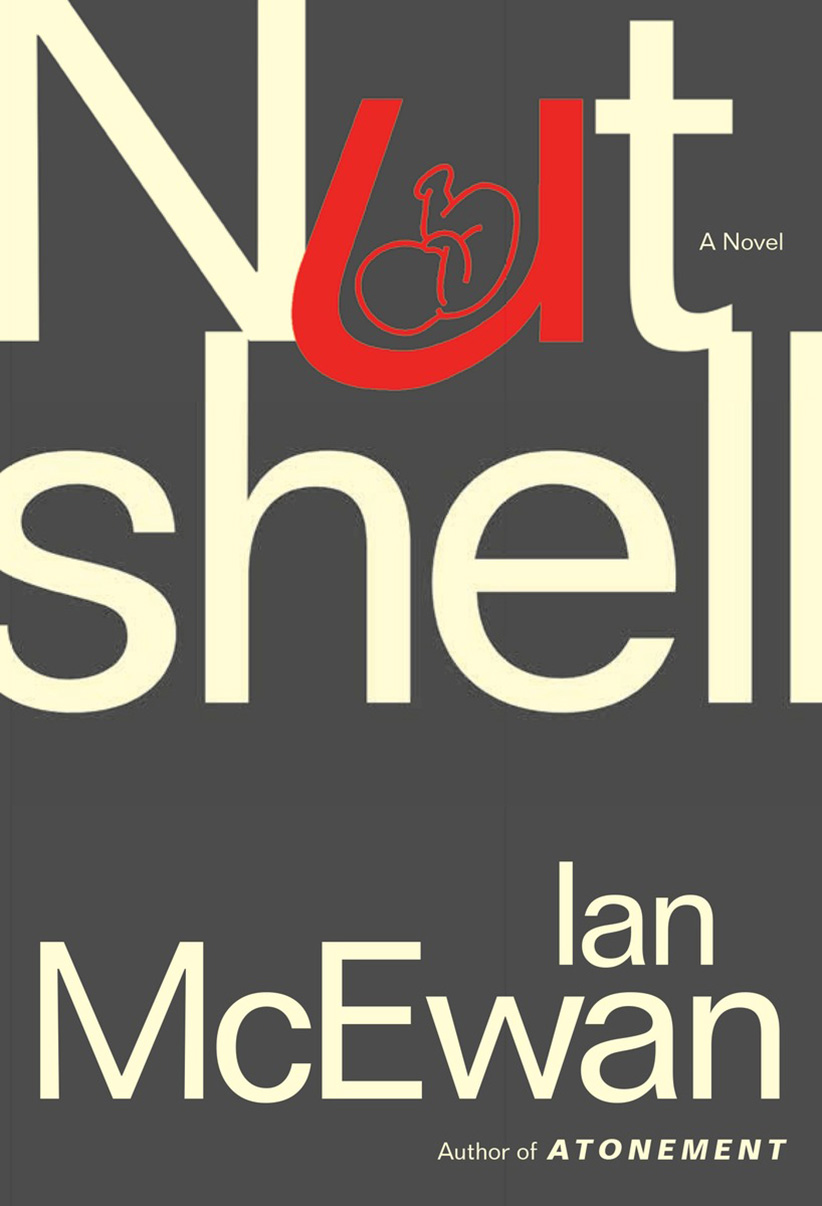

NUTSHELL

By Ian McEwan

A definite suspension of disbelief is required to read this meditative thriller narrated by an omniscient eight-month-old male embryo. Given that its author is Ian McEwan, that leap of faith also requires accepting a fetal commentator well-versed in premier cru wines and Great War poets, as well as given to rumination about nuclear oblivion—the very sort of erudite observations an acclaimed 68-year-old Booker prize-winning novelist might make.

Anyone willing to endure a fetus describing a clock ticking in “thoughtful iambs,” however, is in for a ripping good time. The story is simple, yet tangled. Our yet-to-be-named narrator bristles against being a uterine prisoner, forced to participate in an affair between his beauteous young mother, Trudy, and his father’s brother Claude, “the dull-brained yokel.” The pair lives in the once grand marital home, now reduced to squalor. Their days are spent drinking, having sex and plotting against the cuckolded father, John, a publisher of poetry. The fetus observes all while scheming to get his parents back together. “Like every child of estranged parents, I long to remarry them, this base pair, and so unite my circumstances to my genome.” Saying more would spoil the fun, and the suspense, but the fact the title, Nutshell, is taken from a line in Hamlet is no coincidence. This is that classic play cleverly retold from an anxious womb’s eye view.

Children figure largely in McEwan’s novels, even their titles—The Child in Time, The Children Act—but the worldly, occasionally irritating fetus created to tell this taut tale of betrayal and revenge is singular. “Not everyone knows what it is to have your father’s rival’s penis inches from your nose,” he shares. “The turbulence would shake the wings off a Boeing.” The vulnerability of the unborn to parental action looms throughout. “Against my skull I feel her bladder shrink, and I’m relieved,” the narrator reports after his mother pees some of the vast quantities of wine she’s consuming. A third trimester fetus routinely getting sloshed with Mum will put some off. But that’s not the greatest risk posed by the reckless adults around him, as the narrator knows. Those risks are existential, and force him to confront that eternal dilemma of whether to be or not. As this wry, oddly poignant novel makes clear, it’s often not our choice to make.