In conversation with Canadian punk chronicler Sam Sutherland

On his new book, ‘Perfect Youth’ and the music that changed our cultural identity

Share

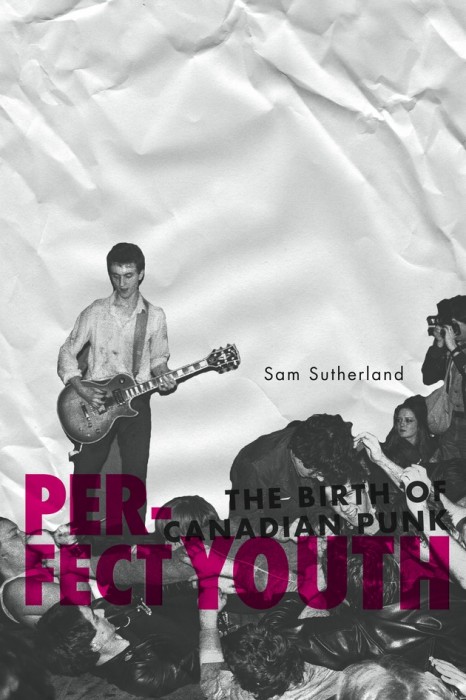

Entertaining books about Canadian culture are few and far between. Perhaps they need a few more narratives involving vomit, electrocution, bar fights, the Mafia, neo-Nazis, k.d. lang and riots 13,000 people strong. That’s what Sam Sutherland has unearthed so brilliantly in Perfect Youth: The Birth of Canadian Punk, a book that is not so much about a much-mythologized genre of music as it is about the Canadian instinct to make something from nothing, about a time (1976-1982) when Canada was still just beginning to assert its own culture, about facing ridicule and being outcast for creating something new and true to yourself, about transforming your entire life into performance art. Sutherland conveys a stunning amount of information from every corner of the country (Meat Cove, N.S.?) in a breezy style that is as fun as the music he’s writing about. And as someone who co-authored a book about post-punk Canadian music between 1985-1995, Have Not Been the Same, I laud Sutherland, with whom I recently had a chance to speak, for adding a crucial component to this country’s musical history.

Entertaining books about Canadian culture are few and far between. Perhaps they need a few more narratives involving vomit, electrocution, bar fights, the Mafia, neo-Nazis, k.d. lang and riots 13,000 people strong. That’s what Sam Sutherland has unearthed so brilliantly in Perfect Youth: The Birth of Canadian Punk, a book that is not so much about a much-mythologized genre of music as it is about the Canadian instinct to make something from nothing, about a time (1976-1982) when Canada was still just beginning to assert its own culture, about facing ridicule and being outcast for creating something new and true to yourself, about transforming your entire life into performance art. Sutherland conveys a stunning amount of information from every corner of the country (Meat Cove, N.S.?) in a breezy style that is as fun as the music he’s writing about. And as someone who co-authored a book about post-punk Canadian music between 1985-1995, Have Not Been the Same, I laud Sutherland, with whom I recently had a chance to speak, for adding a crucial component to this country’s musical history.

Q: How old are you?

A: 27.

Q: That means you were born in 1985—after the period of time you’re writing about, which I’m guessing you cut off around 1982, 1983.

A: Yes, that’s the general point after which you can’t really argue something is first-wave punk anymore.

Q: Could this book have been written by a 40- or 50-year-old, or does it takes someone younger and less jaded to look at this time period with open eyes and fresh ears?

A: I think there is value in coming at these things as an outsider and finding a way to tell these stories that is concise and conveys what was important about them to an audience that wasn’t there. If you were there, you’re then bringing baggage. But being 27 and writing about something that happened in the ’70s, you have to create all that context for yourself, and hopefully that helps build a narrative that other people who didn’t see the Diodes play at the Crash’n’Burn in 1977 can relate to. Something that I hope comes across in the book, something that I hope sells people who aren’t into these bands on their value, is the fact that I’ve come to them without any preconceived notions of their value and worth, and I’ve found so much that excites me there. I’ve read every book I can on the subject. But up until a couple of years ago with certain books and films, there was nothing about Canada—other than your book, Have Not Been the Same, which touches a bit on some punk stuff, but your cutoff point was 1985. I envisioned this to be the logical precursor to it.

Q: That’s good, because my co-authors and I assumed someone was going to write the book you just did. You could have easily just covered Toronto, Hamilton, Vancouver—maybe not even Montreal, because I notice that here Toronto gets four chapters, Vancouver gets four, Hamilton gets two and Montreal, which was the biggest city, demographically, in Canada at the time, only gets one. Was it important to you to also do Saskatoon, Ottawa, and the Maritimes?

A: That was all really crucial to the story I was trying to tell. There is more that connects this country culturally at that time than people think. In essence, the whole book is arguing that there is this Canadian identity that comes out of all these bands, whether they’re from Edmonton or Fredericton, that is tied to the intense cultural isolation of being from those cities at that time.

Q: You also make the case for these bands musically, and not just insisting that they were derivative of what was happening in London and New York—though I’d say many of them were.

A: It varies wildly by the band, but there are specific examples in every city of a band that was not just doing an imitation of the Ramones. Many of them were, of course. A lot of this music is out of print. A lot of it was never even recorded. But there’s a lot of it floating around on the Internet that you can get a decent sense of how a lot of these bands sounded. Without exception, every band did something that was a little bit weird and I would argue it wouldn’t have happened were those bands not from those cities. I even think the outrageously stripped down and hyper nihilistic image and sound of the Viletones feels very Canadian to me. I mean that in a positive sense.

Q: Violence is a common theme in the book. The concept of a punk rock riot is a well-worn cliché, but as you found out, there actually were riots upon riots and hundreds of fistfights at shows. Obviously punk was confrontational, but do you think society was just full of more bored tension back then? Did fights routinely break out at gigs by BTO cover bands?

A: I think a lot of that had to do with the kind of bars that were hosting early punk shows: the worst, most down-at-the-heels s–thole in town, the biker bar, the bar that was literally on the wrong side of the tracks. It seems like violence was just an accepted part of the culture of those early shows. Boredom also plays a huge part in that, and the culture of Canada at that time. The culture is very different now. You’re not bored at the bar if you’re drinking alone because you’re probably on your iPhone looking at baseball scores.

Q: These days there will be a shooting in Scarborough and part of the larger narrative will casually mention that these guys have been uploading all sorts of YouTube videos of songs where they brag about gunplay. It’s off everyone’s radar, in part because everyone at every level of society boasts about being criminal. So the link between violence and music—no one even cares anymore. But the amount of attention back then paid by the mainstream to the Viletones’ first gig: I can’t imagine anyone’s first gig getting covered by the Globe and Mail, never mind a marginal band in a burgeoning fringe culture. Maybe it speaks to what little was happening in Canada at the time.

A: Yeah, the Globe and Mail headline was on the cover of their entertainment pullout after the Viletones’ first show: “Not them, not here!” And the gig was in the basement of a bar. It illustrates how culturally bleak Canada was at that time. There are people who will argue that Yonge St. or Yorkville was cool in the ’60s, but by and large, from everyone I’ve talked to and everything I’ve read and pictures I’ve seen: these were dreadfully f–king boring places to be a young person.

Q: Personally I feel I would rather read about these bands than listen to them; I’ve never been impressed with much of what I’ve heard, outside of the Vancouver bands, who were almost uniformly amazing.

A: Look at Toronto: a lot people there have moved into other creative musical pursuits, with different levels of success. But look at Vancouver: you have Bob Rock recording most of the scene’s biggest bands, a guy who would go on to record Metallica, Motley Crue, the Moffats and Michael Bublé. You have Gerry Barad, who convinced the owner of Quintessence Records to start releasing these albums; he is now chief operations officer for Live Nation. Then you have Stephen Macklam, who managed the Pointed Sticks, and now manages Elvis Costello and Diana Krall. That’s crazy! Think about what those people must have been like when they were 20, how creative and hungry and driven. Even a guy like Larry Wanagas, who managed k.d. lang for many years, started out recording punk bands in Edmonton.

Q: The common theme in this book is that regardless of what you think of the actual music, or even the genre of music, it’s about people making something from nothing.

A: Absolutely. That’s why context is so important. Screaming Fist is great, but it’s not the most important thing. World War III by D.O.A. is great, but it’s not even the most important thing. What’s important are all of the larger ripples that emerged from these little actions that are so outside of whatever cultural box people were living in. Not only do you get great singles like Screaming Fist, but you also get artists like k.d. lang. You also get infrastructure, touring routes: it shapes the way people who follow you look at their cities, their opportunities. That’s even more valuable than a Hot Nasties single on eBay!

Q: Which your book claims that Warren Kinsella, former Calgary punk and now Liberal party operative, will send you himself for the price of postage.

A: Everyone has mixed feelings about that guy. There is no chapter in this book as fraught with drama as Calgary. Those guys all still hate each other; each side thinks the other are huge posers.

Q: You see that in Toronto, too: Viletones vs. Diodes, street punks vs. art school, furious at each other 30 years later. Did you feel you were prying into people’s high school yearbooks here, with people still holding a grudge about a stolen girlfriend?

A: It’s very strange. I’m a hateful, grudge-holding guy; I have been habitually angry my whole life. And now I never want to hate anyone ever again. I finished this book and said, ‘I forgive everyone!’ Talking to someone in their 40s or 50s about a guy they still hate for some perceived slight when they were 17 is sort of really depressing. Not to say that it’s not legitimate, but holding a grudge that long is a lot of f–king work.

Q: If someone had no time of day for the concept of punk rock, what do you think they would take away from this book? I think it’s fascinating as a cultural history, independent of what it’s actually about.

A: I wanted to write a book that someone like me, with a vested interest in these bands, would feel satisfied with, but I worked to position this in the same way that you would an important literary movement or cinematic movement. It’s easily dismissed because music is seen as more entertainment than other art forms, and it’s punk, so it’s seen as being childish. I think Canada is in a moment now, culturally, that even our parents are aware of. There is really great art being made here, and really interesting things are happening in our cities. Not for the first time, but at a level that maybe we haven’t experienced before. What is so important about this story is that it wasn’t happening before this. This is the foundation of everything that isn’t s–t about Canada.

Q: So you’re not a Yorkville guy.

A: No, not a Yorkville guy! Yorkville guys and gals are free to disagree with me, but I think if you appreciate anything about alternative culture in Canada, if you appreciate anything about Canada that isn’t on eTalk Daily, it all starts with these bands and these people: the records they put out, the tour routes they developed. And it’s not just the bands: the managers, the record stores—which were so crucial; the people who went to the shows; the people who sold the clothes and created the aesthetics of the movement. Punk rock in Canada is the foundation of what is exciting culturally about this country in 2012. It affected film, literature, gave room for disparate voices, created an audience and spaces for those voices to develop.