In conversation with Tomson Highway

The acclaimed playwright on being politically incorrect and his trust in the magical process

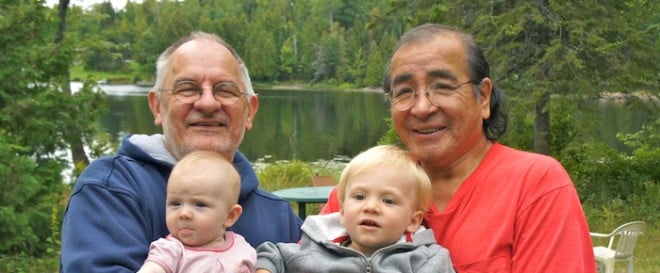

Tomson Highway (right) with Milena Faucher, Marek Faucher and Raymond Lalonde, his partner of 29 years. (Alexie Lalonde-Steedman)

Share

Tomson Highway, the Cree playwright and author whose gripping works about life on the reserve brought him international fame, membership to the Order of Canada and saw him named one of the 100 most important people in Canadian history by this very publication in 1998, is in a state of delight. And not just because The (Post) Mistress, his one-woman musical about a middle-aged letter-sorter in small-town francophone Ontario, was published this month.

Highway cut his teeth by writing work that mixed the spirit of his first language, Cree—the “trickster language,” he calls it—with topics like AIDS, sexual abuse, poverty and racism in native communities. The result is a kind of magical realism which expresses the universal aspects of his stories, much in the same manner a Shakespeare play can be understood without a firm handle on the language. But now, inspired by grandchildren, frequent walks in the Pyrenees and a promise he made long ago, Highway is no longer fuelled by a need for raw expression and survival: he’s revelling in sentimentality and insists it’s not a dirty word.

Q. I know this isn’t your first cabaret, that you mounted one in Toronto during the G20 summit. I imagine writing a play is different than writing a cabaret in obvious ways. But how do you find it different in less obvious ways, what struck you as unique with this kind of process?

A. Yes, The (Post) Mistress started out as a cabaret, the one I mounted in Toronto, and later it grew into this play. My first dream, impractical as it was considering I was a native person from the Nunavut-Manitoba border, was to be a concert pianist. But to compete in that field on the international scene you have to be born in New York or Paris and start when you are three. But I’ve always had music in my head. When I started to be a playwright when I was around 30, I was so poor that I produced the plays myself; I never had enough money to pay musicians or composers, so I thought I’d take a stab at it. So I wrote the music and would frequently end up on the stage playing the music myself, too. I kept doing that and, over the years, the marriage of text and music got closer and closer. When a musical is made, usually the script is written by one person, lyrics by a second and music by a third. But because of my experience in the theatre school of hard knocks, I ended up doing all three and I do it backwards: I write the music, then the lyrics, then connect the songs with a plot. I’ve heard David Bowie cuts up a newspaper and throws the pieces on the tables, taking the little snippets and arranging them randomly, adding his own magic and comes up with the most wonderful lyrics. I work like that, fitting ideas together like a jigsaw puzzle and the script just comes out. It’s a game that I play, a wonderful game. I trust the magical process.

Q. The plays and books that made you famous in the Canadian mainstream are centred around the native community. The (Post) Mistress is centred around a French-Canadian farming village with virtually no mention of natives or the native community. I’ve read that you’ve sort of “left English” as you put it, to spend six months of the year in France and six months in French Ontario. How did this immersion in French culture inspire you?

I fell in love with the French community a long time ago: the culture, the language. When I was a teenager, I saw Mon Oncle Antoine by Claude Jutra—the greatest movie in Quebec cinema history, in the opinion of many. I remember being so moved by this film and I just fell in love with Franco-Ontarian culture. And then I fell in love with a Franco-Ontarian man and then his family and was just absorbed into the Franco-Ontarian community—by love! We also regularly spend time in southwest France where I hike the Pyrenees obsessively. So I associate a love of life with francophones and The (Post) Mistress is about love, love letters and love of life.

Q. Your most popular works are famed for a sort of cultural collision; this play has none of that and is actually pretty sentimental. Bob Dylan tells this story where in the ’70s he was in the studio making an album and was aware that his producer really wanted him to write songs that were more like that early Blonde on Blonde Dylan sound and he says something to the effect that he just couldn’t, he didn’t have it in him and, frankly, that’s just not what he has to say anymore. As you’ve grown as an artist, in age and experience, what is it that you’re now most interested in conveying with your work?

A. I like to convey joy. I want to convey that our primary responsibility on planet Earth is to be joyful: to laugh, and to laugh, and to laugh. I do not believe what I was taught as a child by Roman Catholic missionaries that the reason to exist is to suffer and repent and that the more of that we did, the more deserving we became of happiness in the afterlife. I mean, depressing or what? I’m of the opposite opinion: the way that my native culture works is that it teaches that we’re here to laugh, that heaven and hell are both here on Earth and it’s our choice to make it one or the other.

Q. Was conveying joy in your art always your goal, even when you started out?

A. I didn’t really have a primary goal when I started. My first impulse was to help my late brother, René Highway, to put on shows. He was stuck in Toronto with a stalled choreography career and so I helped him put shows together and they were painful experiences: there was never any money in them and I ended up paying for most of them myself. But when the plays started working, and I realized I had the chops for it, I just kept on going. In those earlier days, my goals were expression and survival and then it morphed into joy. When René passed away at 35 from AIDS, that was the last thing he said to me before he slipped into a coma, “Don’t mourn me, be joyful.” So my job is to be twice as joyful as ordinary people because I promised to be joyful for both of us.

Q. In the past you’ve said that your career as a playwright was destroyed by political correctness: your plays have had large casts of Aboriginal characters and directors were loath to mount productions without Aboriginal actors, fearing a sense of cultural appropriation. Now you’ve been vocal that you don’t think this should be the case and that this kind of thinking is the enemy of art. That a Turkish cast should perform your plays in Turkey, that an Angolan cast should perform it in Angola, etc. Did the idea of gun-shy interpreters ever rattle around in your brain as you created this non-political, one-woman show where the distinguishing characteristics of the lead is that she’s middle aged and can sing well—meaning there’s significant room for interpretation, even to the cautious?

A. I did lose a lot of income in early days because of politically correct potential interpreters that wouldn’t put on my shows. But no, I didn’t think about that when I wrote this play. I just thought about beauty. I don’t think about politics. I’m not political. And I’m not a racist, either; people ask if I like white people and I say I love them, I sleep beside one every night and have for 29 years.

I’m part of the first wave of native writers in this country and we had to be aware of political correctness; it was kind of forced upon us. For the next wave of native playwrights, they should be afforded the freedom to let their imaginations fly. And we all need to help them get there. If a black, Chinese lesbian ends up being cast as the chief of an Indian reserve, then that is the choice of the writer, director and producer and it’s nobody else’s business.

Q. But what about those past directors and producers who have been fearful about the idea of cultural appropriation when casting your plays: “We can’t cast white people in a Tomson Highway play!” What do you think about that? Did you see it as respect or fear?

A. I don’t particularly want to work with people who are scared, for whatever reason. And people who think that way are scared, they’re chickens! I feel most comfortable with people who are brave and courageous. Who are politically incorrect, for goodness sake. I love politically incorrect. I mean, it’s essential for art.

Q. Toni Morrison is often referred to as an African-American woman writer. You’ve been called “the Cree playwright/author” and “the first native playwright to achieve success in Canadian mainstream theatre.” How do you feel about these qualifiers, this language in describing you as this kind of niche artist?

A. I never thought in those terms, I never wanted to be first or the best. You know, I had extraordinary parents, I’m the 11th of 12 children. By the time you get to the 11th, you’ve made all your mistakes and your parenting skills are a fine art. They taught us how to work very, very hard, to be disciplined, to aspire to it. So that’s really all that matters to me, I don’t care what people call me. Though, some people used to say to me, “You love being the centre of attention,” I would just think, “What’s wrong with being the centre of attention?” Actually, maybe that’s the other thing I aspire to.