In conversation with Jeff Lemire

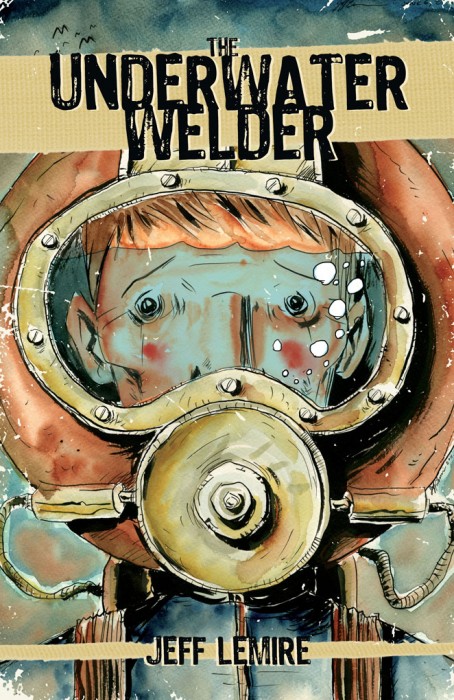

The award-winning Canadian graphic novelist discusses his latest project, ‘The Underwater Welder’

Share

If you don’t know who Jeff Lemire is, here’s why you should: His 500-page epic Essex County, which told three haunted and affecting stories of life in the titular Southern Ontario community, has forever cemented Lemire’s name in Canadian comics history: the book won him a Joe Shuster Award, a Doug Wright Award, and a 2011 nomination for the prestigious Canada Reads where it garnered more fan votes than the other four nominees combined.

If you don’t know who Jeff Lemire is, here’s why you should: His 500-page epic Essex County, which told three haunted and affecting stories of life in the titular Southern Ontario community, has forever cemented Lemire’s name in Canadian comics history: the book won him a Joe Shuster Award, a Doug Wright Award, and a 2011 nomination for the prestigious Canada Reads where it garnered more fan votes than the other four nominees combined.

Lemire hasn’t rested on his laurels: He released the graphic novel The Nobody, about an unwelcome stranger in a small town, for DC Comics in 2009, started a serialized comic book, Sweet Tooth, about a boy with antlers for DC’s left-field Vertigo imprint, and has written for another dozen titles, including Superboy, Justice League, and Animal Man. All are characterized by the themes that Lemire does so well: the isolation of daily life; the love/hate dynamics of family; the burden of the past, and the uncertainty of the future. None, however, explore these themes as wholly and as strongly as the book Lemire has been quietly working on since 2008. That graphic novel, The Underwater Welder, is the culmination of years of work while toiling away at other projects.

Maclean’s spoke with the Lemire about the trajectory of his career, how his personal life affects his writing, and escaping the shadow of Essex County.

Q: What’s your process for creating stories? Do you draw first and look for inspiration there, or is it straight from your head?

A: I’m not a pre-visual thinker, so it tends to be some kind of interesting visual that will strike me, and I’ll start drawing it, and exploring it. Then a story will spring from it. In the case of The Underwater Welder, I hadn’t started doing comics full-time yet, and I was working a night job as a cook in Toronto. The brother of a guy that I was working with was training to be an underwater welder. I’d never heard of that before, and when he was telling me all about it, I was struck by the visual of this guy deep below the ocean in this cool helmet, with fire under the water. It just seemed like such a cool image, so I did a few sketches of it, just for fun, and then suddenly I had a character. Once you have a character, their story starts to come out, and you just build it and build it and figure out what it’s about. It does tend to be all based on stuff that will pop up in my sketchbook. At any given point, you might draw 10 or 20 pages that you might never look at again, but then there’ll be one thing that, for some reason, keeps reoccurring, and you want to keep re-drawing it. That’s usually when you know you have something.

Q: So the idea of Jack being an underwater welder came before the rest of the story?

A: Absolutely. I didn’t know who this character was, I just thought about the visual, which I found fascinating. He was sort of like an astronaut, so isolated and alone with his work. It went from there. I just added dimensions to it: Who this guy is? Where does he comes from? What would make him want to choose something in his life that’s such a lonely profession, so disconnected from the world? What kind of person would choose that, and why? You start asking yourself those kinds of questions, and you come up with answers.

Q: The stories you choose to write tend to focus on the familial.

A: I like telling stories about families and generations of families. I’m fascinated by how a father and son, or a mother and daughter, can be so similar, yet make such different choices in their lives. But you can’t escape who you are, or your family, because things are cyclical. In many ways, we are our parents. Jack is faced with the same things his father was faced with and he can either repeat them or he can decide for himself. Eventually, the book is about Jack’s decision to become his own man and be free from the ghost of his father, which is holding him back.

Q: You’ve spoken about pulling together inspiration for your books from multiple sources. Are there some specific ones for The Underwater Welder?

A: I started writing the book in 2008, so it’s hard to remember what I was into when I started the project. I do know I had been rereading Arthur C. Clarke’s novel version of 2001: A Space Odyssey. I really love that book, and the sense of isolation the character is feeling as he gets further and further from Earth. I love that point in the movie, as well, where he makes contact with the monolith in space and has that psychedelic experience. You can definitely see that stuff in The Underwater Welder. Recently, I’ve gotten into Joseph Boyden, a Canadian author who I think is going to end up really influencing whatever I do next, but it’s mostly other cartoonists that really tend to push my buttons, get me flared up.

Q: Who are they?

A: There’s an Italian artist named Gipi; his artwork is so gorgeous. He does this sparse, really thin line-work with these beautiful washes. That’s something that really influenced the look of The Underwater Welder. All the washes and gray tones I used in that book [were influenced by him]. Then there are guys like J.H. Williams. He’s so experimental in terms of piece layout and the way he panels a page. Guys like them are trying to push the medium, trying to do new things with it, and using the language in different ways.

Q: Why do you think comics are now getting their due as art and literature?

A: I think a lot of it has to do with the number of good books out now. Twenty-five-to-30 years ago, when there was that first wave of what people now call literary graphic novels — Maus, Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen — people first started to take notice of comics as something that wasn’t just for kids. They got really excited about it back then, but beyond those three or four amazing works, there wasn’t a lot more for people to get into. Now, when people get excited about a book like Persepolis, people who aren’t usually interested in comics, there are dozens upon dozens of graphic novels that they can read next. We have a deep enough catalog that people can really get into it and take it seriously.

Q: With the success of an epic like Essex County, was it hard to start a new project?

A: Yes, it made it really hard. This book is about two things: the pressure of becoming a parent, and the pressure of trying to follow up Essex County with something just as good. For me, that was really crippling. I spent months just rewriting and redrawing scenes from The Underwater Welder. I felt like they weren’t good enough, and didn’t live up to what I’d accomplished. Essex County became this insurmountable thing. But looking back now, I see all these flaws, and The Underwater Welder is a much better piece of work.

Q: On page 180 of The Underwater Welder, there’s a Halloween scene where kids are wearing the costumes of some of your comics characters, which strikes me as somewhat celebratory. Do you feel like you’ve “made it”, or do you push yourself hard to always do better?

A: I think both. I feel pretty accomplished now, whereas when I was doing Essex County, I don’t think I had yet found my voice as a storyteller; I found it over the course of doing that book. Nobody knew who I was then, and my work wasn’t out there at all. Now, I feel very happy with the body of work I’ve produced, and I have a solid fan-base, so I do feel like I’ve “made it.” Right now, the minute I finish working on something, I’m already dissatisfied with it: all I see are mistakes, and things I could do better. But, I think whenever I stop doing that and being critical, there will be no point in continuing. I’ll never be truly satisfied with my work; each new project is a new opportunity to do better and explore new directions.