Ai Weiwei, an artist in exile, turns to the refugee crisis

The dissident Chinese exile Ai Weiwei proves perfectly suited to the task of revealing the depths of the refugee crisis with his film, ‘Human Flow’

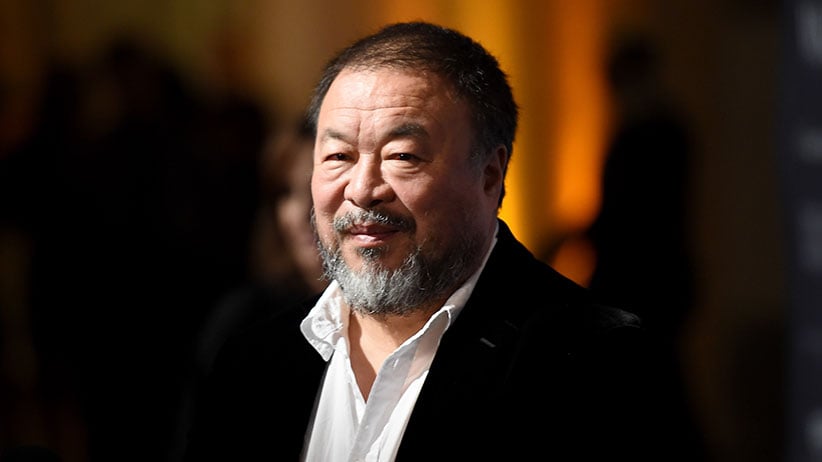

Honoree and Artist Ai Weiwei attends the WSJ Magazine 2016 Innovator Awards at Museum of Modern Art on November 2, 2016 in New York City. (Nicholas Hunt/WSJ/Getty Images)

Share

China’s Ai Weiwei could be considered the most powerful artist on the planet, by any number of yardsticks. He’s the most famous artist to emerge from the world’s largest country, and its most celebrated dissident. He has mobilized projects on a mammoth scale, ranging from the Bird’s Nest Olympic stadium in Beijing (which he helped design, and then denounced) to a Tate Modern exhibit of 100 million hand-painted ceramic sunflower seeds. He became a political folk hero, risking his career and his life by giving the finger (literally) to China’s dictatorship while crusading for human rights. And for his incendiary performance art, he was almost broken by beatings and an 81-day prison term of solitary confinement in 2011, followed by indefinite house arrest.

In 2015, Ai finally won back his passport and fled the country to live with his girlfriend and his son in Berlin. And in exile, the 60-year-old artist has reinvented himself once again, making a monumental mark as a director with the documentary epic Human Flow, which amounts to the most devastating, comprehensive and immersive vision of the world’s refugee crisis ever filmed.

But he still doesn’t know why Chinese authorities set him free. “They’ll never let me know,” he said in an interview with Maclean’s this week after the recent Toronto premiere of Human Flow, which opens commercially Oct. 20. “I was truly lucky to have the chance to leave. It was extremely difficult. Two of my lawyers are still in jail. Activists and lawyers and dissidents cannot get out. Even their wives and children cannot get out.”

MORE: Jia Zhangke on redemption, Chinese censorship and Ai Weiwei

With Human Flow, Ai has trained his magnifying gaze on an entire population trapped in horrific limbo. To convey the sheer scale of a catastrophe that has produced a global diaspora of 65 million refugees—a stateless nation roughly the size of France or the U.K.—Ai shot in 23 countries with a crew of 200. In each case, he employed aerial drone shots to portray the refugee camps, vast cities of khaki tents that, from the air, dissolve into a desert landscape like a grid of dunes. But on the ground, his camera captures intimate, often casual moments of people trying to maintain their dignity, even their joy, in the most desperate circumstances. And as he telescopes between panoramic quilts of displaced humanity to tender portraits of individual lives, the result is a film of breathtaking power.

Ai has previously directed small documentaries in China, but Human Flow is his first major film. Weighing in at two hours and 20 minutes, it violates an unwritten rule: documentaries that go beyond 90 minutes do so at their peril, unlike blockbuster dramas. But asking an audience to sit still for that long to spend time with refugees who wait years for freedom seems an essential part of the exercise. “Yes, people have to make an effort to see a film like this,” he says. “But in comparison, a young boy may wait five or ten years to get an education, and the average refugee spends 25 years as a refugee.”

MORE: Why Chinese artists are making waves—and getting away with it

Simply dressed in black cotton shirt and trousers, his hair and beard more neatly trimmed than in the movie, Ai Weiwei has a quietly commanding presence, soft-spoken and patient, but with a weary air of resignation that suggests doing publicity is not his favourite pastime. As a film guy, I had the naive impression that making a movie would be a bigger deal for him than creating armadas of art objects for a museum. Not so. “The only difference,” he says, “is that a film reaches a very general public, so you have to do a lot of promoting in every city. You have to convince people to see the film, which you don’t do with an art exhibition. All my exhibitions were breaking records for visitors. I would easily get a few hundred thousand people to look at the work. But film seems difficult, especially documentary. I just found out that in Toronto, a very liberal city, we may reach an audience of 20,000 to 30,000. To me it’s a big disappointment.” Then, warming to the math with the calculus of a man who once filled a museum with millions of fake sunflower seeds, he added, “If you want to get 20,000 people, that means in a theatre of 200 you have to show it 100 times! This is the reality of film. Very few people still go to theatres.”

MORE: Ai Weiwei’s exhibit at the AGO, a reminder of a man who isn’t there

Invited by Six Degrees, an annual conference on “global inclusion,” Ai was visiting Toronto for the first time to receive the Adrienne Clarkson Award for Global Citizenship, and to promote a film that was clearly a humbling experience for him. As a celebrated dissident artist, he once loomed as China’s Buddha-like answer to Michael Moore, a larger-than-life trickster who played a defiant game of tag with the regime’s censors until they called his bluff with cruel consequences. He grew up a refugee in his own country, the son of a poet who was branded an enemy of the state. The year Ai was born, his family was banished to the Gobi Desert by Mao Zedong’s government. And while he’s no Angelina Jolie as he roams through the refugee camps with his Human Flow crew, he remains a figure of considerable privilege. So he keeps a modest profile in the film, popping up every now and then as a comforting soul who offers solace and diversion to those around him. Migrating from one camp to another, he manages to submerge himself in his own film.

“You have to be quiet, shut up, and just watch,” he explains. “At the same time, you have to be patient, and let the audience come to its own conclusion. This is not an educational film. It’s about beauty, feeling, suffering, empathy, and how to share. It’s about tolerance.”

Yet there’s much to be learned along the way, as subtitled statistics float across the screen: the up-to-the-moment number of almost half a million Muslims escaping rape and murder in Burma; the one million refugees in Macedonia who over the years have squeezed through a crude metal gate the size of something you’d find in a farmer’s field; the three million trapped in Turkey as Europe turned its back; the Palestinians’ grim world record for having the largest refugee population of more than four million; the fact that whole generations in Gaza have never known a world without a wall or checkpoints; and a note that the number of countries that have fenced-off borders has risen from 11 to 70 since the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.

But keeping pace with the numerical tide are lines from ancient poets, like this one from the 11th-century Persian mystic Baba Tahir: “I am that sea and have come into a bowl.” And as we hopscotch from one refugee camp to another, from the Mediterranean to Iraq, from the ruins of Lebanon to sub-Saharan Africa, the declension of catastrophe is framed with jarring interludes of visual poetry. Human Flow’s aerial vistas recall Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky’s epic images of environmental ruin, which portray the infernal beauty of the oil sands and tailing ponds without needing to pass judgment. There’s a satanic majesty to the blackened skies and orange blaze of oil wells torched by ISIS forces retreating from Mosul. As hordes of African refugees are systemically swathed in golden space blankets, then marched into buses, it’s like an alien abduction. And the cool cinematic neutrality of a drone shot that shows a tent city as an intriguing off-white canvas, where insects slowly turn out to be people, is deeply disturbing.

“It becomes so abstract,” says Ai, “then gradually you see some movement. It’s beautiful and shocking at the same time. As you jump from one location to another, you need an overview. Luckily, we have a technology—only God can have a view like that. It shows how fragile our human condition can be.” And it suggests the perspective of a world that wants to keep its distance from what’s happening on its borders. In Germany, where refugee camps are cleaner and better organized, the camera flies indoors, over a white-cubicle maze of numbered bedrooms without ceilings in an aircraft hanger. The camp looks like a movie set, an Orwellian parody of suburbia.

MORE: Ai Weiwei’s beef with Lego is a fight of free speech vs commerce

At the core of Ai’s vision, which slides so fluidly between global and individual arenas, is a challenge to the conventional wisdom that, amid so much mass suffering, an individual—one of countless sunflower seeds—is powerless to effect change. When I ask if he does in fact feel like one of the world’s most powerful artists, Ai says, “I feel powerful when I’m really defending essential values such as human rights. If you still have a voice and can constantly talk about freedom of speech, you feel powerful. But you also feel disappointed because those things require everybody to act. Everybody has to make a decision—to make one action against those human conditions.”

Finally, I ask about everyone’s elephant in the room, Donald Trump, who is, after all, a man deeply in love with scale. Has Ai imagined showing him Human Flow?

“He’s always a mirror in my mind,” he says. “Maybe the film would give him some new thinking about building this horrible wall between the U.S. and Mexico. This is an absolutely ridiculous thing to do. He should think about the emperors in China who built the longest wall in human history. It has only become a ruin and a tourist site.”

Ai allows himself a smile. He may not enjoy doing promotion, but he knows that, with any luck, he’s on a long march to a captive audience at the Oscars, where he’ll be able to remind the world, and Donald Trump, which way is up.

MORE ABOUT CHINA:

- Ivanka Trump’s Chinese business ties shrouded in secrecy

- The hidden risks of opening up trade with China

- The worrying silence around Canada’s trade talks with China

- China warns U.S. against starting ‘trade war’

- China urges U.S. to ‘hit the brakes’ on North Korea threats

- China to cut off imports from North Korea under U.N. sanctions

- United Nations imposes new sanctions on North Korea

- It’s time for Canada to stand up to China’s censorship crackdown