Al Purdy comes to life in a new documentary

Long-time film critic Brian D. Johnson pays homage to a voice that still resonates

Share

Al Purdy has a certain reputation, captured neatly in what’s rapidly becoming his best-known poem, “At the Quinte Hotel,” where the beer on tap is described as half fart and half horse piss/ and all wonderful yellow flowers. He’s the sensitive (as “Quinte” says of its author, four times, no less) award-winning artist described, the year before his death in 2000, as “the best Canadian poet” ever for Michael Ondaatje. And he’s also the hypermasculine, working man’s poet, fond of fighting, drinking and womanizing, who would argue and insult, then go “pee on your car tire,” as an indulgently acerbic Margaret Atwood remarks, twice, in the subtle and engaging film Al Purdy Was Here.

The documentary by Brian D. Johnson, formerly Maclean’s long-time film critic, pays playful homage to what can be called tourist-board Al, with more than one reference to the crowd-pleasing “Quinte” and shots of Sensitive Man ale rolling off the bottling line—complete with “contains farts and horse piss” labels—at Barley Days brewery in Ontario’s Prince Edward County. But the film, which will premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on Sept. 15, also thoroughly subverts that image, revealing a Purdy who contains, Whitman-like, multitudes beyond the tough guy, and who, especially in his influence on contemporary artists, deserves as much as anyone the epitaph engraved on his tombstone: Voice of the Land.

AL PURDY WAS HERE (Trailer) via Vimeo.

Born in Wooler, in the unforgiving Loyalist landscape north of Lake Ontario, in 1918, Purdy dropped out of high school to hop a freight train west during the Depression. Somehow, he developed the idea he would become a poet—or, more precisely, that he was a poet already in his innermost self—even if that was a job description that scarcely existed in his native land. Purdy travelled all over the country, working in factories and producing his first, self-confessedly bad poetry. But he never gave up, and that, says Ondaatje, is where Purdy’s heroism lies.

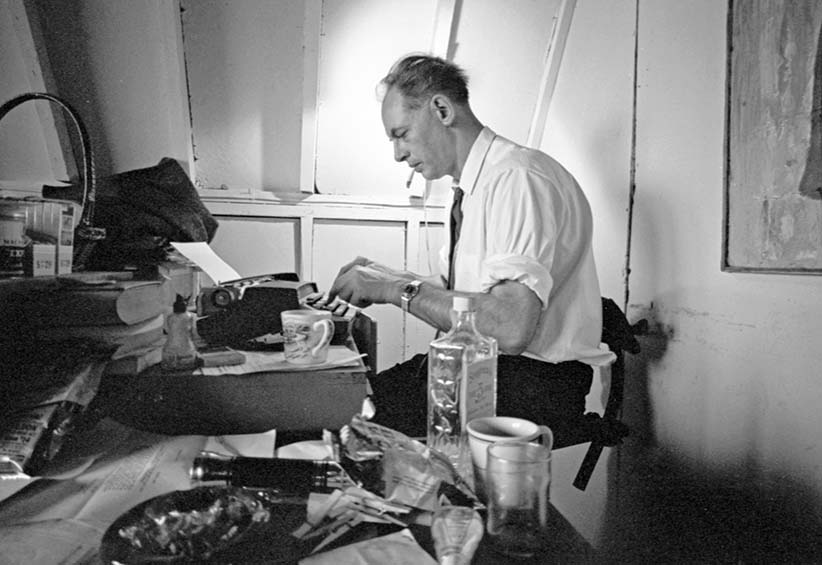

In 1957, returning to his home territory, the poet and his wife, Eurithe—the 90-year-old living star of Al Purdy Was Here, a woman as stoic and rock-ribbed as the landscape itself—built an A-frame cabin out of found lumber near Ameliasburgh in the county, now prime weekend-home territory for Toronto’s affluent. There he found the voice—curt, elegiac, rough, coloured by humour and anger, described by Michael Crummey as “the first poetry I heard that sounded like my father and his friends sitting around, talking”—that makes poems like “The Country North of Belleville” and “Necropsy of Love” continue to resonate now. In 1965, Purdy won the first of his two Governor General’s awards for The Cariboo Horses.

As success came, Purdy turned the A-frame into a rural mecca for younger poets and blossoming CanLit stars such as Atwood and Ondaatje. Johnson’s film is framed around the A-frame, and the drive to raise funds to restore and maintain a poet-in-residence program in it. The campaign reveals Purdy’s enduring appeal: The Tragically Hip’s Gordon Downie reads “At the Quinte Hotel” at a fundraiser; Doug Paisley, impressed with Purdy’s work since he heard the poet read in a seedy eastern Ontario bar, sings a ballad—the name of which, Transient, summons up Purdy’s remark about what to do with this “bloody brief life”—about a homesick poet riding the rails back from Vancouver; novelist Joseph Boyden and Inuit throat singer Tanya Tagaq perform “Say the Names,” Purdy’s hymn to Indigenous place names; Sarah Harmer sings her own Just Get Here, about the idea of an artists’ refuge.

And the first artist to find refuge in the A-frame—Toronto poet Katherine Leyton, 32, who took up summer residence there in 2014—encountered the many Purdys for the first time. “I had thought of him as a young guy’s poet who wanted to write about beer and violence,” she says in an interview with Maclean’s. “Then I read some of his really wonderful other poetry and, living in his house, I started to write about the things he wrote of, about your smallness in so vast and epic a countryside.” Voice of the Land, indeed.