‘Boyhood’: A long decade’s journey into film

Richard Linklater’s decade-spanning feature film isn’t just ambitious–it’s a haunting look at the ‘voluptuous panic’ of aging

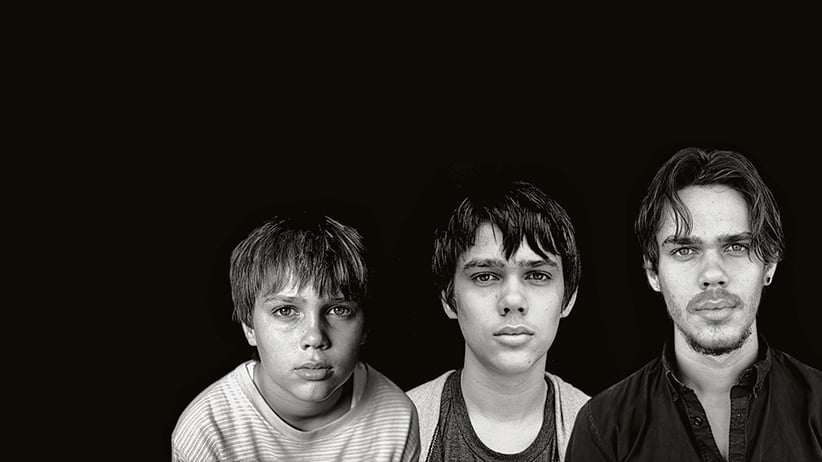

Ellar Coltrane stars in Richard Linklater’s “Boyhood” filmed over a period of 12 years.

Share

Years ago, in a university survey of American cinema, a professor prefaced a screening of Robert Altman’s ambling epic Nashville with a bracing admonition, something to the effect of, “If you don’t like Nashville, you should have serious misgivings about what you want out of a motion picture.” Being told to like something can feel a bit hectoring. But some films just may demand that sort of line-in-the-sand passion. Boyhood, the latest from American filmmaker Richard Linklater (Before Sunrise, Bernie, School Of Rock), is one. It’s a film this writer has watched, twice now, largely behind a mist of tears provoked by the film’s grace notes of fuzzy adolescent nostalgia.

Plenty has been made of Boyhood’s production. Linklater gathered his cast for a few weeks a year over the course of more than a decade, mapping the adolescence of a Texan boy named Mason Evans Jr. (Ellar Coltrane) in close to real time. The boy’s aging is marked as much by the acne flecking his face as by progressing pop cultural references (Dragonball Z, Harry Potter, Halo) and political movements (Bush’s Fallujah invasion, the Obama-Biden ticket). Imagine Michael Apted’s Up Series (documentaries that catch up with 14 British people every seven years) crossbred with Linklater’s own meandering day-in-the-life surveys (Dazed and Confused, Slacker, the Before trilogy) and you begin to get a sense of the scale of the accomplishment.

“Because it’s such a conceptual effort,” Malcolm Harris writes in the online magazine The New Inquiry, “it seems almost unfair to judge Boyhood as a narrative feature.” But arguing that Boyhood is something other than a conventional movie, discounting it as “conceptual,” glosses over what Linklater has achieved. In a film that moves without contrivance with the young man at its centre, nothing and everything happens. Characters learn lessons and grow up and go camping and shoot guns and fall in and out of love—Patricia Arquette, as Mason and Samantha’s upwardly mobile single mom, cycles through husbands, her desire for security drawing her to a string of abusive drunks. Linklater lets these things happen at the unhurried pace of time itself. He even lets plot threads develop in ellipses, suggesting micro-dramas in the spaces we don’t see, as when a teenage Mason Jr. argues with his dad about his rightful claim to a vintage GTO, promised to him (so he argues) in a scene we never see.

In films like School of Rock, Linklater has expressed a rare sensitivity to what one Boyhood character calls the “voluptuous panic” of youth. Kids are free to drink beer and smoke pot and horse around without the hand of narrative repercussion slamming down. As in Bernie, Slacker and Waking Life, Boyhood empathizes with the oddballs that dot the periphery of a certain American adolescence: the Tourettic loners stalking the suburbs, the conspiracy theorists slumped in the booths of all-night diners, the Bible-thumping backwoods Texans more commonly rendered as no-dimensional caricatures.

Watching these characters orbit in and out of one another’s lives gives a sense of actually watching people—not canned archetypes, but fully formed people—get older. Time’s movement over the film establishes an uncommon intimacy with its cast, a sense that we truly know them. It feels like a consummate work for Linklater, who has long been engrossed with the spaces people occupy, how they change over time—whether in the all-night party of Dazed and Confused or the 18 years separating Before Sunrise from Before Midnight. He even has the indolent liquor-store clerk from Dazed reprise his role, suggesting that all his films take place in the same narrative world.

This proximity is the core of Boyhood, and it’s more impressive than managing a cast’s schedules for 10-plus years or making nine feature films while shooting it. The gimmick becomes invisible, and Boyhood feels less conceptual than classical: form and narrative in harmony. Rare is a film that’s so bottomless in its generosity and affection.