Brian D. Johnson reviews ‘Last Stand,’ ‘Mama,’ ‘On the Road’ and ‘Quartet’

This week: Schwarzenegger, Chastain and that ‘Twilight girl’ chase a Mexican bandit, a mother from hell and a bohemian dream

Share

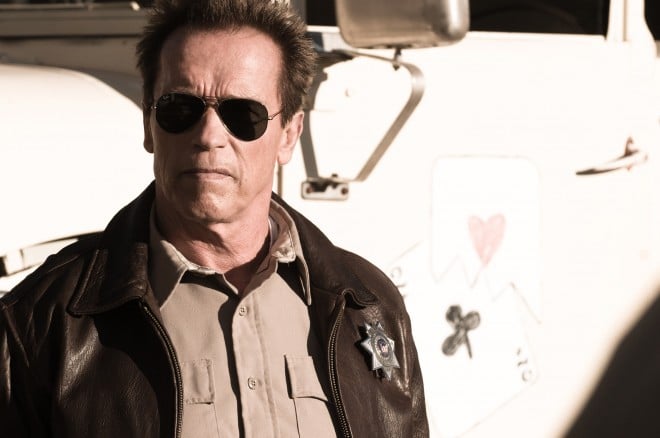

He’s back. Now that his marriage and political fortunes have gone up in smoke, Arnold Schwarzenegger makes a game attempt to re-ignite his career as a Hollywood action hero with his first lead role in a decade. In The Last Stand, The Governator re-enters the fray as a kind of unplugged Terminator, an old-school sheriff in a sleepy Arizona border town who ends up battling a fugitive Mexican drug lord in an armed stand-off that unleashes more firepower than the Alamo. Landing in the thick of the current debate on gun control, the timing couldn’t be worse, especially with Arnie using a school bus as a lethal weapon, along with a vintage arsenal of big, bad-ass guns that turn the sheriff’s one-horse town into an NRA fantasy camp.

The Last Stand‘s formulaic scenario, of a crusty lawman hauling himself out of semi-retirement, could be seen as Arnie’s Unforgiven, but with way more cheese and no gravitas. At best, it’s a guilty pleasure.

Directed by Korea’s gonzo action director Kim Jee-Woon (The Good, The Bad and The Weird), it has a ramshackle plot, in which the boss of a Mexican drug cartel, Gabriel Cortez (Eduardo Noriega), escapes from FBI custody while in transit, then makes a beeline for the Mexican border in a super-powered Corvette with a comely FBI hostage in tow (Genesis Rodriguez). Sheriff Ray Owens (Schwarzenegger) and his dusty little town just happen to be in the middle of the drug lord’s escape route, where a sadistic henchman (Peter Stormare) and his gang are preparing his way.

Oscar-winner Forest Whitaker flails away in a thankless role as the frustrated FBI agent in charge of the mission to re-capture Cortez. It doesn’t pay to be black or Mexican in The Last Stand, as the Sheriff and his ragtag posse—which includes a scared deputy (Luis Guzman) and a zany gun nut (Johnny Knoxville)—mete out some good ol’ boy frontier justice.

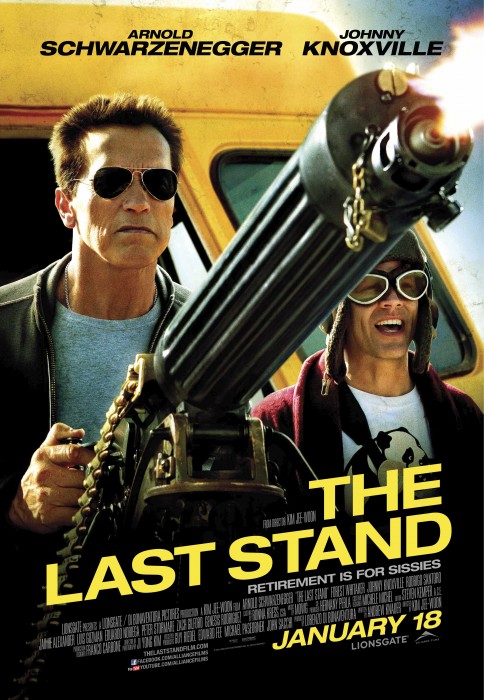

Curiously, it’s impossible to find a film still on the distributor’s website that actually shows Schwarzenegger brandishing a gun—perhaps he doesn’t want to become a poster boy for gun violence during this sensitive time. But there’s nothing equivocal about the poster for the movie (left), which captures the kick-ass spirit of the film’s civilian call to arms; it could be retitled: “Last Stand for the Second Amendment.”

As the action climaxes with a marathon shootout, there are some cool touches, notably a car chase through a field of corn so high neither driver can see each other. Arnold slips back into his familiar persona as an animated block of granite with relative ease. And it’s fun to see him back in the saddle, even more so because he’s a bit creaky. Kim Jee-Woon judiciously puts the action on pause for requisite intervals of comic relief. But as every strand of Schwarzenegger’s contrived dialogue strains to graduate into an immortal one-liner, the movie seems all too conscious of its pop cult mission to reconstruct the icon that is Arnold. And despite the title, it’s not his last stand. Soon we’ll see him co-starring with Sylvester Stallone in The Tomb, and he has several more movies in the works. Maybe, like the Rolling Stones, Arnie and Sly will get more grotesquely fascinating with age, as they push the upper limits of the action hero. One can only hope.

Mama

Here’s a Jessica Chastain we haven’t seen before. She’s a far cry from the tenacious CIA agent of Zero Dark Thirty, or even those saintly wives she played in Tree of Life and Take Shelter. In Mama she portrays a punk rocker who likes bonking her boyfriend (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau) and has no plans to be a mother—until a psychologist (Daniel Kash) bribes her to play surrogate mom to a pair of wild-child orphan sisters who have grown up feral. In an opening flashback, we see the two kids dragged into the woods by a demented dad on the run after killing their mother. They hole up in a cabin, where Dad is murdered by a mysterious force—a ferociously jealous ghost they call Mama. She hides in the walls, taking the form of some kind of Super Mildew. We know she’s real, and so do the girls. Everyone else assumes Mama is just a figment of the their hyper-active imagination. The audience is in on the secret from the start, and the suspense is geared to the slow reveal of the Mother from Hell to the sisters’ unsuspecting foster parents.

This debut feature from Andy Muschietti bears the imprimatur of executive producer Guillermo Del Toro. Shot largely in Pinewood Toronto Studios, it’s got a strong visual style, and the narrative clicks along with an almost playful energy as Muchietti teases out the horror. But this is the kind of thriller that is most effective, and scary, only as we are fed fleeting glimpses of the creature. In the last act, as the ghoul is fully revealed in all her hideous glory, the suspense drains from the narrative. You get the sense that the filmmakers are working overtime to show off Mama as a meticulously crafted special effect. And as the plot paints itself into a diabolical corner, a live action thriller congeals into another movie altogether, a Gothic showpiece of digital craft.

Chastain, however, can do no wrong. It’s intriguing to see her not only refashion her hair colour, but to go through a chameleon character change—as a reluctant mother, whose life consists of sex and music, and who abandons both as maternal passion slowly overpowers punk insouciance. Also, the child actors portraying the two feral children are both riveting: Megan Charpentier (Red Riding Hood) and Quebec’s Isabelle Nélisse.

On the Road

I still haven’t had a chance to re-screen On the Road since catching its world premiere in Cannes last May. At the time it left me impressed but unmoved. The level of earnest, dutiful responsibility that went into bringing Jack Kerouac’s novel to the screen seemed oddly out-of-synch with the reckless spirit in which the book was written—and by which its characters lived. Or, as I wrote from Cannes: “Studiously researched for eight years, and faithfully rendered onscreen, this loving ode to On the Road must be one of the most mature, responsible films ever made about drugs, drink and debauchery.” In that dispatch, I went on to describe the Cannes press conference for the film, at which Kristen Stewart talked about performing her first nude scene, and Viggo Mortensen, who’s cast as William S. Burroughs, unfurled a Montreal Canadiens flag and talked about the pertinence of mass protest.

As for the movie, it sits well in my memory. But the memory is faint. And Salles (Motorcycle Diaries, Central Station) is a director I greatly admire. Since Cannes, he has apparently re-cut the movie, so with all due respect I should reserve judgement until I catch up to it.

Quartet is a movie for people who found The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel too exciting. Sorry, that’s a cheap shot, but there’s an element of truth to it, although I actually liked Quartet better than the coy romp of Marigold Hotel, which also featured the great Maggie Smith. Not to be confused with The Late Quartet—that wonderfully overripe mix of music and promiscuity—Quartet is a drama so tame that, in a blockbuster world, it seems strangely audacious. As with Marigold Hotel, whenever we see a movie devoted exclusively to old folks, it’s implied that its mere existence is a bold victory of artistic maturity over Hollywood’s ageist monoculture.

Based on a 1999 play by British writer Ronald Harwood, Quartet marks Dustin Hoffman’s feature directing debut. And for an actor who’s now 75, and in the third act of his own career, it seems designed as an adoring tribute to aged actors and the art of acting, even though his cast are portraying musicians. The story is set in Beecham House, a retirement home for singers and musicians, who stage an annual gala performance. A flurry of anticipation ripples through the home as a famous opera singer moves in—an imperious diva (Maggie Smith). She wants no part in the gala concert, and so the residents conspire to convince her otherwise—including her old flame (Tom Courtenay). The story is modest and predictable. There’s an airless quality to a film of elderly performers portraying elderly performers, with just the right blend of tender fragility and tart wit. But Hoffman has marshaled a Who’s Who ensemble of British actors, including Smith, Courtenay, Billy Connelly, Michael Gambon, Pauline Collins and opera singer Gwyneth Jones. And within its narrow ambitions, the film achieves an undeniable charm, enlivened with a sentimental flush of solidarity for seniors.