‘I rather like the idea of defying death’: Q&A with Christopher Plummer

The legend of stage and screen speaks openly about mortality, his legacy, and why Canadians need ‘goosing’

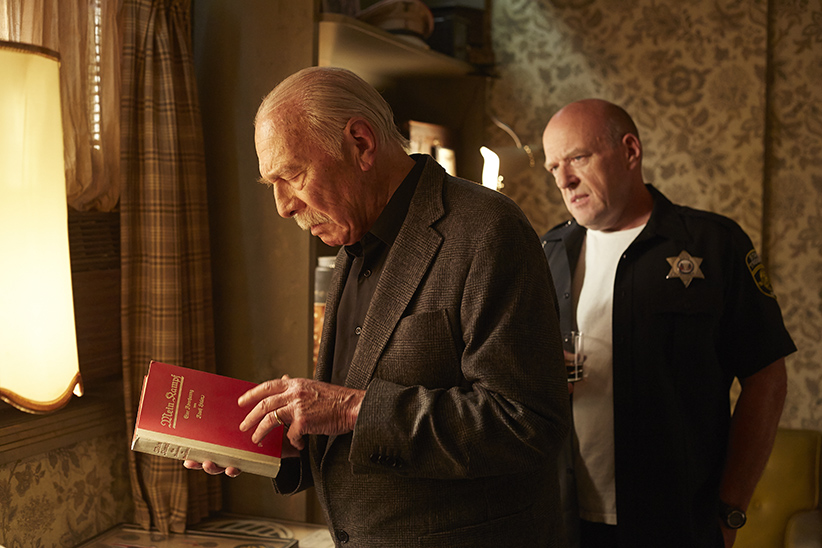

Still from Christopher Plummer’s new film “Remember”. (Sophie Giraud/Remember Productions Inc)

Share

In his day, Christopher Plummer was a renowned rogue—a ladies’ man with a turbulent temper, and a gleeful drinker. (“I was born in Toronto in 1929, and the idea of prohibition was so abhorrent to me that, at the age of one, I moved to Montreal,” he jokes today.) But, these days, the man often lauded as one of the finest performers of the postwar generation is in a peaceful, reflective mood. But he’s hardly done working: At 85—three years removed from becoming the oldest person ever to win an Academy Award for the film Beginners—the Canadian icon of screen and stage is a star again. In the surprising new film Remember, directed by Canadian Atom Egoyan, he plays a dementia-afflicted senior who criss-crosses America to seek revenge on the Nazi guard who killed his family, now living under an assumed name. Plummer reflects on what it means to be Canadian, the terrors of aging, and the 50th anniversary of The Sound of Music, the movie that defined his career—to his chagrin.

Recently, there has been some angst about the future of Canadian film—the idea that anglo-Canadians don’t want to see anglo-Canadian films. You’re a Canadian, in a film made by a Canadian. Is that a feeling you get?

No, I don’t get that feeling. I don’t live here, so I’m not au courant with all the shenanigans that are going on. I just do what I want to do, and if it’s a rather interesting script—which I found Remember certainly was—if it happens to be Canadian, that’s fine; or if it’s Swahilian, fine with me. Doesn’t matter. I asked for Atom, because I had worked with him before and I knew him and he was a friend, and I needed a friend behind the camera in this particular, very difficult assignment. Challenging, exciting, fascinating—but not easy.

Being Canadian—when I do come here, it is a preoccupation of the Canadian. They bring it on themselves. They want to say: “But you were doing fine when you were ignoring the fact you were Canadian. Why do you want to bring it up and smash all your hopes?”

There’s this desperation for people to be famous and Canadian. We always ask: What does it mean to be a Canadian famous person—in any field?

Yes, and I knew some of the famous Canadians. I even met Billy Bishop, at one point. Billy, all he wanted was a nice blond on each arm; he didn’t care if he was Canadian or Brit. He was a hero. Boom. That was enough. It’s amazing. I don’t think the press help; they love criticizing it, and I’m with it. Canadians need goosing every now and then, confidence-wise.

So you don’t feel the need to fly the flag for Canada?

No. I was an instant rebel, because I grew up at a time when professional theatre—or anything professional, really, in a funny way—didn’t exist. There was an amateurism about Canada. It was charming, but it drove you absolutely mad. We all used to always be regaled by people saying, “Oh, I saw you in the play the other night; my, you were so good. But what do you do for a living?” And that, I thought, was so Canadian. Goddammit, man! I do actually get paid. It may be $25 a week, but I am a pro!

Your career began as a stage actor, though there weren’t many repertory theatres in Canada at the time. Why did you stay?

I started in Montreal rep, then I went to Ottawa, which was a professional theatre, and I stayed there for a year. Then I got into radio. Actually, great writing was going on there. But the rest of Toronto didn’t seem to know anything about what was going on, artistically.

You could have gone anywhere.

Well, yeah, but it costs money to go anywhere. But I did, and I suddenly left. And I’m glad I did, because I was able to come back.

And then I noticed that, the minute you get acclaim from other countries, and they recognize you without any sort of resentment—when they welcome you, when they appreciate you, [and] you come back home with this added experience of being on this world stage—Canadians start to resent you for being famous, or being recognized. I guess . . . they want to pull you down to that comfortable, amateurish level.

I don’t think that exists now. I hope not; I don’t think it does. But, every now and then, there’s that feeling.

Of course, one of the things that really got you major acclaim was The Sound of Music, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Although you’ve done so much in your career, you might be best known for your role as Captain von Trapp. Yet you’ve never quite been comfortable with that.

Well, simply because it is a very famous movie, which is not my fault. And the movie is actually very good. I think it’s the only family movie that’s left. I don’t think there’s another family movie that comes near to the family-movie quality of it. I thought Julie, whom I’m a great friend of, and I adore her, [is] marvelous in a very icky role. She did it beautifully and simply, and sang it beautifully, and was beautifully produced by a very good director, Robert Wise. I just didn’t happen to think my part was very exciting . . . That’s the most famous movie. I’m up there, and boom-boom in my un-favourite role—one of them, anyway. It’s not that I hate the film; it’s just that it wasn’t my cup of tea, that’s all.

But you’ve referred to it in the past as treacly. For a long time, you only referred to it as “S&M.” Why have you changed your tone?

Because it keeps on lasting; it goes on forever. I keep saying, “It’s like a bloody albatross; it hangs over one’s head.” There’s something kind of admirable about it. It’s really survived, because it’s the only one in existence that has that kind of family spirit, in the days of innocence that are now no longer with us. But my career as an actor is far more powerful than that. That’s only because the movie’s world-famous. So you’re stuck.

But it was wonderful for your career.

Because Sound of Music was very hot and huge—though it wasn’t very well-reviewed in America—it didn’t matter. It was very hot, and I was offered jobs. I’ve always been very lucky. I’ve never been out of work—thank God, touch wood—and I have that to thank for it. And it got me the best tables at restaurants, which is terribly important.

Did you get the sense that the movie arrested your early career, by limiting the roles you were offered?

In my mid-30s, it was an awful period. I didn’t know if I was a leading man or a character actor. On the screen, I’m talking about, not the theatre. In the theatre, I was having a ball, and I was lauded in the theatre. I won prizes. But in the movies—enh. It wasn’t until my 40s came along, when I played in John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King, a good movie, where I played the role of Rudyard Kipling. That’s when I started enjoying myself. I stopped worrying about my profile. “Are you shooting it at a good angle?” That’s all you’re thinking about when you’re a friggin’ leading person.

You’ve described The Man Who Would Be King as the film that flipped a switch for you, where you understood what it meant to be a screen actor. What was the moment?

John [Huston] was an extraordinary director, because he didn’t direct at all. He said some things to me that were so revealing, very briefly, and I sort of shrugged it off. But he taught me an enormous amount.

One was—it’s hard to explain, because you take the advice, but then a window opens and you can see all sorts of things that you didn’t see before, just from one sentence. It may not have anything to do with what you’d done, but it just opened. It happened to be, near the end of the picture, Michael Caine as Peachy Carnahan comes back, and his head is brought forward; he’s been decapitated. And I’m supposed to say something to him, and I couldn’t get it right. John finally said, after about Take 5: “Chris, take the music out of your voice.” So I read it absolutely dead. Immediately, the expression was real and changed. I wasn’t pushing, I wasn’t saying, “This is a great moment.”

I would have probably known how to do it on the stage without thinking, but, on the screen, though I had done several movies, I wasn’t quite comfortable. But that made me instantly comfortable, and it made me feel, for the first time, like I belonged in the cinema.

In your newest film, Remember, you play Zev, a man afflicted by dementia and fits of forgetfulness. This is an affliction of the elderly, largely. Was that something that scared you, playing something that hits so close to home?

Well, it’s happened to me on stage. It’s happened to a lot of people, and it’s the scariest feeling in the world. But it’s not dementia that we’re having; I suppose it’s overconfidence, which leads to a lack of concentration. You’re doing something you’ve done so many times and, suddenly, you’ve forgotten one word, and the one word can take care of five pages. And suddenly, you’re standing there. It happened to me twice, so it’s something that I think about. But, thank God I’m in this profession, because our business is to learn lines, to read and retain; it’s exercise for the brain. So, for the most part, it is okay.

But a role like this forces you to consider your mortality. Is that discomfiting?

Yes, it is discomfiting, but that’s one of the reasons I wanted to play him. I wanted to experience that in him. And the more documentary realism I could get, the better. I don’t think, however, he notices that, because Zev plays only in the present tense. Everything is in the present tense. Everything is in denial for so long that he only has one road.

I suppose the undergirding premise of these questions is that I’m assuming death is a looming terror, something to fear. But I shouldn’t assume. Is that something you fear?

Well, I’m not exactly comfortable with it. I rather like the idea of defying death. That’s why I think Cyrano de Bergerac was wonderfully and romantically conceived. Even Lear tries to fight death at the end, and there’s something rather marvellous about his last flight of temper. Yeah, I want to go on doing this for a long time; I don’t feel ill or anything. I don’t want death to suddenly interrupt what I’m doing. I don’t like the idea of death at all, thank you very much.

It seems there’s more interest lately in the inner lives of the elderly, and more roles for older actors. Do you think this a golden era for older actors?

Yes, they are, suddenly, which is very strange to me, except, of course, we all live with more mortality because we’re all on drugs. So we appear younger, and we are more vital; it is extraordinary. So the youth aren’t quite as bored as they used to be—or thought they had to be, impatient with age.

In your fantastic memoir, In Spite of Yourself, you wrote this: “’It came to me like a ray of truth that there are only the rarest few born into this world who are truly good humans and, I realized, with a sharp little pang of sadness and envy, I could never be one of them.” Do you truly not see yourself as a good person?

That was about Boris [Karloff], who was just such a generous man; it just exuded from him. He had no side; it was very rare. And of course, I couldn’t get anywhere near that. He really was a generous, good-hearted man. He loved others. And yes, I really meant that. And I wasn’t asking for sympathy, because I think a lot of us don’t deserve the accolades one could have given to a Boris Karloff, who was such a gentle giant.

Was that a revelation you could have had only later in life, as you were writing your memoir?

Oh, I knew it then, 25 years ago. It hit me; oh God, it really hit me between the temples. I knew that, because I was behaving very badly and living a kind of loose life. Of course, one is made to feel immediately guilty. And it hit me.

Was that a turning point?

No, I went off thinking, “Well, at least I’ve cleared the air.” [Laughs.]

There’s this, too: “I’m a complete hypocrite, of course, torn between the thrill of mob recognition on the one hand, and my aversion to the sheer vulgarity of it on the other.” Do you still have that view of fame, at age 85?

I’m very happy where I am, really. I’m happy that I’m not that famous. And I’m happy that I’m famous enough, and mostly for good reasons. I think there’s a certain respect from people, despite Sound of Music. I think somebody, at least, remembers that I did other things, as well.

Do you ever find yourself wishing you were more famous?

You mean the kind of fame that Arnold Schwarzenegger had, or these kids now, in those action movies? No, I never wanted that kind of fame. That was the vulgarity. Kids became famous without any training, without anything to fall back on. And they’d last about 15 minutes.

You’ve long been an advocate for the theatre. Do you think actors should do the stage before the screen?

Oh God, yes, you’ve got to. And the very best screen actors all came from the theatre. Spencer Tracy. Some of the most famous people you wouldn’t think of. Gene Hackman.

These days, I’m not sure people share your opinion.

No. It’s a pity. It’s where the best language is.

Do you find yourself considering your legacy more and more?

No, I try not to. Actually, when I hit 75, 80, I felt like I was coming to the end of that, and I suddenly felt like I wanted to do something really contemporary, and be contemporary. I buried myself so much in the classics that I felt, “Well now, I’ve played all the big parts, whether badly or goodly, I don’t give a damn, but at least I’ve played them all. Now, let’s start again. Let’s start the whole career again.” And it makes you feel like you’re beginning again, it really does.

This interview has been condensed and edited.