Into the deep: Inside Rob Stewart’s mysterious death, and his parents’ fight for answers

Rob Stewart was an ardent conservationist, and acclaimed for his film ‘Sharkwater’. But when he slipped beneath the waves, he left behind an unfinished final work—his grieving parents’ own passion project

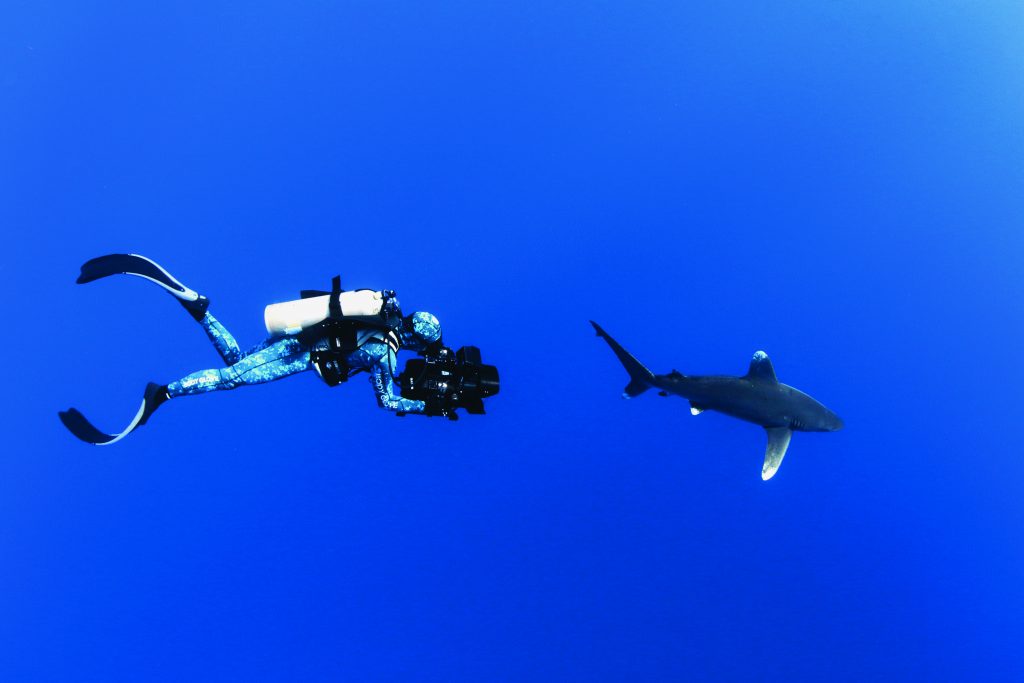

Rob Stewart during production of Sharkwater Extinction. (Will Allen/Sharkwater Extinction)

Share

On Jan. 31, 2017, acclaimed documentary filmmaker Rob Stewart boarded the dive boat Pisces on the tiny island of Islamorada, just south of Florida’s Key Largo. His destination: the Queen of Nassau, a wrecked century-old Canadian steamer sitting 70 m (230 feet) below the ocean’s surface. More specifically, he hoped to capture footage of the elusive sawfish that reportedly swam through the sunken wreck. Resembling a child’s drawing of a ferocious sea creature—a five-foot saw attached to a 20-foot fish—the sawfish was once common in the tropical waters of the Atlantic. Like so many sharks and rays, however, it has been hunted to near extinction. Today it only appears to divers fleetingly, like a strange dream, before vanishing back into the deep.

Accompanied by a small crew—the boat’s captain, David Wilkerson; friend and collaborator Brock Cahill; dive instructor Peter Sotis; and Peter’s wife Claudia, a doctor—the 37-year-old filmmaker dove deeper than he ever had before. Stewart didn’t find his subject on either of the two planned attempts that day. When they surfaced from the second dive, the team realized they’d left a grappling hook on the wreck attached to a buoy on the surface. Sotis and Stewart decided to dive again to retrieve it. When they resurfaced, just after 5 p.m. EST, Stewart gave the “okay” sign. Sotis, however, was in obvious distress. As he began climbing into the boat, it was clear he needed medical attention. Sotis passed out briefly, and the people on the boat rushed to get him oxygen. When they looked back to the water, Stewart had disappeared beneath the waves. His body was found three days later.

In the year and a half since Stewart’s death, questions about exactly what happened that day have swirled, provoking a wrongful death lawsuit, finger-pointing and speculation in the small, passionate world of scuba diving. Theories abound, but even the cause of death remains an unsettled question. Meanwhile, his parents, Brian and Sandra Stewart, have rushed to get his final movie to the Toronto International Film Festival for its premiere on Sept. 7. Completing the film has meant reliving the final months of his life, investigating his last moments and, all the while, trying to figure out how to continue his legacy.

Brian and Sandra Stewart were at work—sitting in the Toronto boardroom of Tribute, the movie publication they co-founded—when they got the call from the U.S. Coast Guard telling them their son had disappeared. The couple scrambled to find a flight, eventually arranging a private plane and arriving in the Florida Keys at dawn. They landed in the middle of one of the largest searches in coast guard history, with planes donated by Jimmy Buffett and Richard Branson, and divers arriving from across the continent. Despite the sprawling search, their son’s body was found on the ocean floor, just metres from where he was last seen.

The couple had always worried about Rob. They’d imagined him getting arrested in a corrupt corner of the world or contracting a tropical disease—maybe even getting murdered by black-market fin dealers, like the ones he exposed with Sharkwater, his 2006 documentary that racked up awards and led to bans on shark-finning in countries around the world. But they had never fretted about their son in the water. “The last thing we worried about was Rob diving,” says Brian.

Even as a kid, Stewart had been as comfortable in water as on land. “Whenever we went camping he was the first one in the water and the first one with something in his hand—a frog, a turtle, whatever,” his father says. He would spend hours snorkelling, exploring every corner of their Muskoka lake. And when he was 13, he convinced the entire family to get their scuba certification: He wanted to go deeper, to stay down longer.

Tyler MacLeod, a childhood friend, remembers Stewart as a chubby kid with a slight stutter and a collection of animals that seemed to grow larger and more exotic every year—from fish to snakes to, at one point in high school, a massive marine iguana that glared at you threateningly whenever you entered the room. When the two of them left for university at Western, MacLeod watched his friend’s childhood fascination with animals turn into a hardened environmentalism that could sometimes seem out of place on the London, Ont., campus. “A lot of our friends were talking about rugby practice or parties,” says MacLeod. “All Rob was ever talking about was saving the planet.”

As a conservationist, Stewart was fearless and passionate, an inveterate high-fiver who lived his life according to a blunt logic. We were slaughtering the world’s sharks and in the process putting the entire ocean at risk. So wouldn’t it be crazy not to do something about it? He would have seemed naive if he wasn’t so persuasive.

MacLeod worked on Sharkwater with Stewart, cobbling it together with his friend over five years. When it was released, Stewart became a minor celebrity in the conservation world, a handsome and charismatic true believer who drew people into his orbit. Julie Andersen was a young ad exec when she met Stewart after a 2007 screening in New York. “Within four days I was in Toronto,” says Andersen, who went on to found the advocacy group Shark Angels. “Literally, after meeting Rob, I sold my business, sold my car, sold my house and changed my life completely to save sharks.”

At the time of his final dive, Stewart was working on his follow-up film, Sharkwater Extinction. He wanted to show how many sharks were still being illegally hunted across the globe, often ending up in products like pet food and cosmetics. “I think individually he has had more of an impact on shark conservation than any biologist,” says Chris Harvey-Clark, a friend and marine biologist who teaches a shark course at Dalhousie. “The first day of the course, I go around to the 18 kids and ask them, ‘Why are you in this room?’ And the majority of them say, ‘Because I saw Sharkwater when I was a kid.’ ”

For Stewart’s friends and family, the news of his disappearance felt like a strange and impossible hoax. Stewart was a survivor, after all. Rationally, everyone knew the chances of him being found alive were slim, but a collective magical thinking had taken hold. “For some reason, we all just believed,” says Andersen. What if he had stayed afloat and simply been taken by the Gulf Stream? “This was Rob. He was superhuman. There was no possible way he wasn’t on a boat full of hot college coeds in the Bahamas, drinking coconuts.”

For the Stewarts, too, the fact that their son had died in a simple scuba diving accident just didn’t make sense. They’d seen him throw on some fins and a mask, take a deep breath and swim the length of a lake. “We knew right away that something was amiss,” says Sandra.

Rob Stewart was an expert scuba diver, but that day in the Florida Keys was one of his first times filming with a rebreather. While a conventional open-circuit scuba apparatus sends a diver’s breath out in bubbles, rebreathers are a closed loop, “scrubbing” exhaled breath of its carbon dioxide and adding oxygen. They let divers go deeper and stay down longer. They’re also nearly silent and don’t produce bubbles, which can scare off a skittish creature like a sawfish. “The price you pay is that these systems are more technically complicated,” says Neal Pollock, an experienced diver and the first research chair in hyperbaric and diving medicine at Laval University. “There are more things that can fail.”

To learn how to use the complicated equipment, Stewart had turned to Sotis, an instructor and the owner of a rebreather supply shop in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., called Add Helium. Online, Sotis touted his abilities as the leader of a dive team that “pushes the limits as they explore deep walls in excess of 600 feet, deep wrecks and extreme caves.” But Sotis had a divisive reputation in Florida’s diving community, and a checkered past. In 1991, he was one of three men who broke into a jewellery store, smashing the glass cases and stuffing jewels into duffel bags before jumping into a getaway car. Sotis was sentenced to three years for armed robbery.

In the weeks before Stewart’s final dive, Sotis was once again in legal trouble. In late December 2016, Shawn Robotka—a minority owner in Sotis’s business—launched a lawsuit against him, accusing his partner of selling military-grade diving equipment to a “known militant” in Libya, despite warnings from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. He also accused Sotis of buying scuba tanks that weren’t compliant with the Department of Transportation, mislabelling them, then selling them. (Sotis and his lawyer did not respond to requests for comment. In court documents, they call Robotka a “dissatisfied investor who has concocted a frivolous lawsuit to exert financial pressure on Sotis.”)

Beyond his legal troubles, Sotis was known as a diver who was willing to test the boundaries of what was safe. “He had that reputation of being like, ‘Oh, f–k it, we’ll dive deeper and faster,’ ” says Andy Brandy Casagrande IV, a National Geographic underwater cinematographer who collaborated with Stewart, travelled in the same small Florida diving circles as Sotis, and once bought rebreather equipment from him.

The dives that Sotis and Stewart did that day in Florida indeed pushed the limits. “Most people would say that if you’re diving in the 200-plus-foot range, it’s probably smart to limit it to one dive a day,” says Pollock. Two dives was tempting fate. Three dives was hubris. “It’s not that it’s guaranteed to be unsafe,” Pollock says. “It’s that it’s really pretty cavalier.”

In March 2017, the Stewarts launched a lawsuit against Sotis, his wife, Claudia, Add Helium and Horizon Dive Adventures, the owners of the Pisces. None of the parties have filed a statement of defence; Horizon asked for the proceedings against it to be stayed, arguing the incident was “caused solely by conditions beyond its control.” The Stewarts wanted to know why someone hadn’t been keeping an eye on Rob when he surfaced. Sotis and the rest of the crew “had a duty to exercise reasonable care for the safety of its passengers,” the Stewarts say in their statement of claim.

(The defendants are not obligated to respond in public; a statement of defence will outline their position.)

At the same time as the Stewarts were trying to find answers about their son’s death, they were also pushing forward with his last film.

Stewart had shot hours and hours of footage, but his parents didn’t know if it amounted to a movie. After talking with documentarians from across the country, they met with Nick Hector, an acclaimed editor who had met Stewart just a few months before his passing. Hector told the family his approach would be simple. “We have to make Rob’s film,” he told them. “We will try to get inside his head and tell the film in his own words.”

The Stewarts gave Hector their son’s footage, as well as Rob’s notes about the movie, his diaries, his iPad, his emails and the scribblings he’d made that, in sum, mapped out an aesthetic vision. Hector also brought on Sturla Gunnarsson, an award-winning documentary filmmaker, to act as a creative consultant. Over nine months, they painstakingly constructed a movie out of the hundreds of hours of film Stewart had shot.

In January 2018, Hector invited the Stewarts to his studio to watch the first cut of the movie. The film is fast-moving, jumping across the globe. Stewart flies a drone over a warehouse in Costa Rica to reveal illegal shark fins drying on the roof. He talks his way onto a boat in Cape Verde and films a mountain of butchered blue sharks. He stakes out fishermen off the coast of Los Angeles who are carelessly killing marine life with drift nets, and is forced to flee when they open fire on his crew. It’s also inevitably elegiac: each new locale comes with a dateline, the calendar slowly ticking down toward Jan. 31, 2017.

In Hector’s studio, watching the rough cut, the Stewarts broke down in tears.

“I don’t know how they do it,” says the editor. “They’ve had to watch the last year of their son’s life on screen over and over.” For the Stewarts, though, the rush to finish the film has allowed them to put a pause on their grief. “We haven’t had a day off since his death,” says Sandra. They’ve been too busy to mourn. The unfinished film has left a kind of penumbra around their son’s life: a hazy in-between zone in which his death is somehow not yet settled, his final words not yet delivered.

That work has come alongside their lawsuit, which has been endlessly delayed as the various parties jockey with one another. Even arriving at an agreed-upon cause of death has been impossible. According to a report by Dr. Thomas Beaver, then the Monroe County medical examiner, Rob’s death was due to hypoxia, or lack of oxygen. Last month, however, the Belgian company Revo, manufacturers of the rebreather Stewart was using, filed a motion to intervene in the case, saying that data downloaded from Stewart’s rebreather showed that his oxygen levels were more than adequate when he surfaced, ruling out lack of oxygen as a cause of death. In the absence of hypoxia, and with the knowledge that both Stewart and Sotis suffered an episode at the same time, Pollock says the evidence points to decompression sickness, the result of a too-aggressive approach that left both men addled and incapacitated when they surfaced. “Sotis was just the lucky one,” says Pollock.

For the Stewarts, each new revelation about their son’s death has been painful. They’ve tried, unsuccessfully, to stay away from the scuba forums, where every report ignites a new round of amateur investigation. Ultimately, they say, definitive information won’t come until the coast guard releases its long-anticipated report on Stewart’s death. It’s possible that may not happen until 2019; the lawsuit could drag on for years after that.

With the movie wrapping, the distractions might soon end, but the Stewarts don’t plan on stopping. In many ways, they say, finishing the film is just the beginning of a new phase. After TIFF, they’ll head to the Atlantic Film Festival to promote the film, then Vancouver, then Calgary. Then, of course, there are festivals in the United States and Australia, and the movie’s premiere on Amazon in April.

Then there are Rob’s other projects. His interests sprawled, including ocean acidification, deforestation and the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef. Each presents a way to extend their son’s story. “I don’t think we’ll ever be done,” said Brian.

In the Tribute boardroom just weeks before the movie’s premiere—posters and images of their son peeking out from every corner—the family was still experiencing the world through Rob’s eyes. “Rob used to go off and film for three or six months at a time. We’d get these cryptic texts saying, ‘Hey, I’m in Borneo and I’m diving with Dave and it’s awesome and I saw some amazing stuff,’ ” Brian says. “It’s almost like he’s still out there shooting, because for the last year and a half, we’ve been looking at footage of Rob.”

In one of the film’s final scenes, we see Stewart and Sotis on the Pisces as it chugs through the water, setting off to find the sawfish. The sun glistens off the gently swelling ocean. “These are rebreathers,” Stewart says to the camera, holding up the gear. “We’re going to use this new technology to get deeper than we’ve ever been before to film a creature that people have rarely seen in the wild.” Stewart jumps into the ocean. He adjusts his mask. And then his camera captures his slow descent into the water before fading to black.