The arrival of Denis Villeneuve

How Quebec filmmaker Denis Villeneuve catapulted from indie Canadian cinema to Hollywood stardom—all while keeping his signature style intact

Left to right: Amy Adams and director Denis Villeneuve on the set of the film ‘Arrival’. (Handout/Paramount Pictures)

Share

Denis Villeneuve is exhausted. The Quebec filmmaker is on the phone from Budapest after a long day shooting Blade Runner 2049, his blockbuster sequel to Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi classic. Now he’s trying to change channels, and re-wrap his mind around the metaphysical puzzle of Arrival, his other sci-fi movie. Opening Nov. 11, it stars Amy Adams as a linguist recruited to communicate with extraterrestrial visitors that have parked a dozen giant ovoid spacecraft around the globe. Arrival seems to have all the trappings of a Hollywood blockbuster, but its elliptical narrative, which is almost devoid of violence, leads us into an existential riddle of memory, grief and circular time. And Villeneuve’s own explanation of the film could not be further removed from a Hollywood tagline. “It’s a film about intuition and our intimate relationship with death,” he says, “where we’re going into a new territory and lacking words to describe it. As North Americans I feel we’re not very comfortable with the idea of death. We try to push the boundaries and act and live as if it didn’t exist.”

Even after working on five English-language features, the 49-year-old director speaks with a marked Québécois accent, and as he searches for a thought, his voice frayed by fatigue, he apologizes: “At the end of the day, I think my brain is slowly dying.”

The man has a right to be tired. No director has vaulted from indie Canadian cinema to a major Hollywood career in such spectacular fashion. After a string of award-winning Quebec features, including Polytechnique (2009) and the Oscar-nominated Incendies (2010), in just three years he’s tackled one genre after another in an escalating series of Hollywood productions: Prisoners, Sicario, Arrival and the upcoming Blade Runner 2049. And what’s extraordinary is that so far he’s done it without compromising his distinctly dark signature. So you have to wonder: how has he gotten away with it?

“It was not a conscious plan,” he says. “When I was living in Montreal, I wasn’t dreaming of going to Los Angeles and doing American movies, because for me it was dangerous territory. I was hearing all those horrific stories of filmmakers being crushed by the system there, and was not interested in getting in line behind 5,000 filmmakers waiting to do Legally Blonde 7. The only way I thought it possible, is if I was invited.”

On the strength of his Quebec films, Villeneuve was offered Prisoners (2013), a grim abduction drama, and he had the nerve to deliver a 2½-hour cut, which somehow survived unscathed. Sicario, a thriller about Mexican drug cartels, was another heavy, brutally violent film. The director says he was able to handle it only because he’d committed to direct Arrival next. “After Polytechnique, Incendies, Prisoners and Sicario,” he says, “I was starving for some light.” It seems counterintuitive to hail a film about death as a source of light. But Arrival—based on a short story by Ted Chiang (“Story of Your Life”)—is a shimmery spectacle, with a cosmic riddle at its heart that recalls classics like Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 2001: A Space Odyssey, or anything by Terrence Malick.

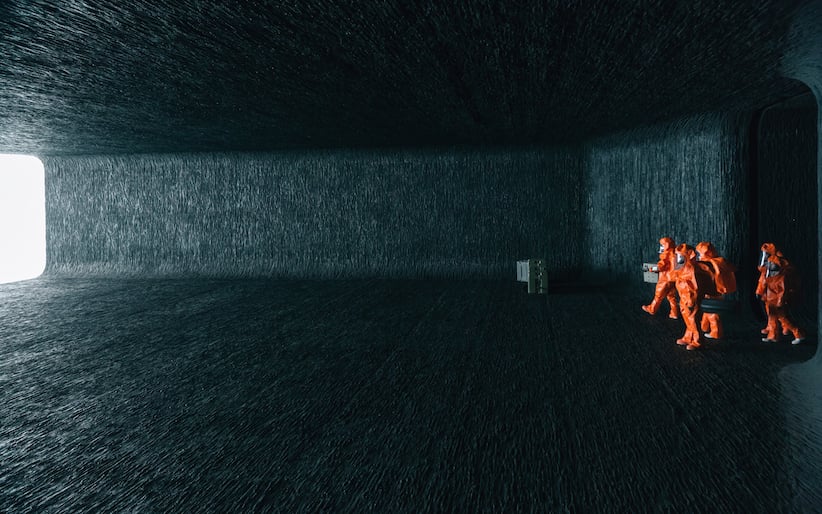

Villeneuve says it’s impossible to avoid influences. “When we put five people in [hazmat] suits touching a black object with fear,” he says, “we were very aware of what we were doing. There are a lot of people who walked this path before us. I thought it would be great fun, and a bit of a challenge, to create a new species, a new biological form. And I realized after a few weeks that it would not be a gift but a nightmare.” Adds Villeneuve, who is impeccably polite: “My respect for filmmakers like Spielberg or Ridley Scott—all those filmmakers that created strong visual worlds—I just admired them that much more.”

But in the claustrophobic tension of Arrival, you can also detect influences that are closer to home, from the films of David Cronenberg to Villeneuve’s own creepy landscapes in Polytechnique and Enemy. But what’s most exhilarating is Arrival‘s sheer originality. As the linguist tries to interpret the aliens’ whale-like communications, the story unfolds as an ethereal exploration of language, embodied by inkblot graphics and spooky sound design.

In an industry where it’s notoriously difficult to make mature, contemplative films with real money, it’s a miracle that Villeneuve was allowed to spend 50 million Hollywood dollars on a movie about understanding aliens rather than fighting them. That’s because the film was independently produced, he says. “The project attracted the big studios, but when they got attached they were very aggressive, and one thing they put in their deal is that I’d have total freedom,” Villeneuve says, laughing, as if he still can’t quite believe it. “I had total freedom! But the movie is a strange object. It’s not like a conventional alien invasion movie. Paramount loved the film but it’s a challenge for them. It’s a UFO for them.”

Arrival is positioned as an Academy Award contender. It shows Villeneuve colouring outside the lines of Hollywood formula, and taking the kind of high-wire risks that have endeared him to critics. Sicario and Prisoners earned four Oscar nominations, and won great acclaim. But unlike his previous two movies, which reworked violent genres, Arrival offers the kind of transcendental drama that should also appeal to Academy voters. And the whole movie is powered by a multi-level performance from Amy Adams, who is due for an Oscar after five nominations.

“For this movie,” says Villeneuve, “I had to choose the perfect actress, somebody who had the ability to tell several stories at the same time, with not a lot of dialogue. Amy had that strength and profoundness. She was my first choice and to my great surprise she said yes right away. Usually actors can take six weeks or two months before they answer. But she fell in love with the screenplay. She was a real trooper, very easy to direct. The only thing that was difficult is that Amy is very hard on herself. She’s never satisfied. She’d be doing amazing things in front of the camera, and we were all in tears, moved by her performance, but she was never totally satisfied. It’s a perfection thing. She needs that tension inside her to push her to the limit.”

Villeneuve shot Arrival in Montreal and rural Quebec with a largely Canadian crew. He found a location outside Rimouski, near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, to serve as the Montana meadow where the aliens have landed their towering, egg-shaped spaceship. “It was strange for me to create something foreign in Quebec,” says the director. “But as a Canadian it was a pleasure to bring U.S. money back home.” (The location also allowed Villeneuve to stay close to his family in Montreal; he has three children, aged 17, 19 and 20.)

Filming Blade Runner 2049, which stars fellow Canadian Ryan Gosling, has been a more gruelling experience. The studio publicist warned me not to ask him about the film, which is shrouded in secrecy. But Villeneuve talks about its epic shooting schedule, which has ranged from Vancouver to Budapest. “Right now my energy is fading away,” he says. “When you make movies in Canada, it’s 35 days of shooting, 40 if you’re lucky. In the States, I made movies with 50, 55 days. This is my first shoot of 100 days. I’ve discovered what stamina means. It’s really difficult to keep the energy level alive. I keep my head above water because of the energy the actors are giving me. But next time if ever anyone offers me a movie of that scope, I would think about it twice because it’s a big commitment. People warned me—it’s like making three movies in a row.”

Now that Hollywood has granted Denis Villeneuve dreams he never even knew he had, his horizons seem unlimited. But he’s has come to learn the inevitable flip side of any sci-fi fantasy: be careful what you wish for.