Happy 500th birthday, Raphael cherubs

Exhibit touts heavenly tots from painting to T-shirts to toilet paper

Share

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. Through their striking composition or beguiling subjects, there are images of the Renaissance which ensnare the viewer’s gaze with a force undiminished by the passing of centuries. They seep deep into the collective imagination, only to resurface in popular culture with timeless appeal—and at times the tawdriest of kitsch — on objects as diverse as nail files and hangover kits. Raphael’s Sistine Madonna is one such painting.

Five-hundred years have passed since the Italian master painted his iconic image, which hangs today in the Old Masters’ Picture Gallery in Dresden, Germany. The gallery is celebrating the anniversary with a special exhibit, whose assorted display encompasses everything from 16th century sketches to modern-day toilet paper. Indeed, the exhibit is not only a vivid retelling of the story of the Sistine Madonna’s origins and reception. It also showcases the painting’s broader influence on global pop culture – owed in large part to the certain air of ennui of its two lackadaisical cherubs.

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Photograph by Jürgen Lösel)

© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Photograph by Jürgen Lösel)

Raphael had not yet turned 30, in the summer of 1512, when he was commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint an altarpiece for the monastery church of San Sisto, in the northern Italian city of Piacenza. The commission, which sought to honour the city’s return to the Papal States after its liberation from French troops, came at a time when Raphael was busily painting his frescoes for the Vatican’s papal chambers. Yet the Sistine Madonna was to be a new departure from the artist’s previous work, including its so-called “sister” painting completed just the year previous, the Madonna of Foligno.

“The Madonna of Foligno shows a vision seen by the saints inside the painting,” explains the exhibit’s curator, Andreas Henning, to Maclean’s. “But what makes the Sistine Madonna so new is that it is a vision painted for the spectator outside of the painting.”

Though the Sistine Madonna depicts a sacra conversazione – a form of “holy conversation” common in Virgin and Child images at the time – Henning believes that its “new, outstanding” composition helped lay the “foundation on which the painting became so famous in the 19th and 20th centuries.” Gone is Mother Mary sitting meekly on her throne. Instead a curtain parts before her as she strides across the clouds, with veil billowing in the wind.

Infrared images taken of the Sistine Madonna reveal that Raphael painted with swift, confident brushstrokes. But they also shed light on the only part of the painting reworked by the master’s hand: Mary’s distraught expression.

“Normally Raphael’s Madonnas look very lovely,” says the director of the Old Masters’ Picture Gallery, Bernhard Maaz. “They are playing with Jesus, they are sitting and contemplating. But here she is anticipating what will happen about 33 years later, the death on the cross. And this means she anticipates her own experience, which is to lose a child as a mother.” Andreas Prater, an art historian at the University of Freiburg, speculates that in San Sisto’s monastery church, Raphael’s Madonna would have stared out at the cross, the “symbol of the Passion”, mounted on the rood screen separating the chancel and nave.

For nearly 250 years, the Sistine Madonna was admired only by the cloistered monks of San Sisto. It was not until 1754, after two years of strained negotiations, that August III, the Elector of Saxony, was able to acquire the painting for Dresden. Packed in a box with hay, it made its way on a six-week journey across the Alps. Winter rain seeping into the wooden box meant that the hay had to be replaced at a tavern along the way. When the painting finally arrived in the audience chambers of the royal palace, it is said that August III pushed aside his throne with his own hands and exclaimed: “Make way for the great Raphael!”

Despite its triumphant welcome, the Sistine Madonna was overshadowed for decades by Correggio’s Nativity, considered to be the jewel of the Saxon monarch’s collection. The royal gallery’s chief superintendent, Carl Heinrich von Heineken, even criticized the Sistine Madonna, comparing Jesus’ appearance to that of a “peevish child” and casting doubt on the authenticity of the two cherubs at the painting’s lower edge.

The Dresden exhibit retraces the Sistine Madonna’s steady rise in popularity during the Romantic era through a variety of visual and written accounts. In 1776 the writer Goethe asked in wonderment: “Did Raphael paint something different, something more than a loving mother with her first and only son?” A magazine published in Spain and Latin America even assured its readers, in 1839, that a trip to Dresden to see the Sistine Madonna would be more satisfying than visiting Egypt’s pyramids or the amphitheatres of Antiquity.

From the beginning of the 19th century, the Sistine Madonna’s heavenly toddlers became famous in and of themselves. They started to be reproduced, detached from the painting, in everything from armbands to almanacs. German children adopted their poses in photo studios. An American lard refinery even morphed the cherubs, in 1890, into winged pigs.

Raphael had added the angels as an afterthought, simply to enhance the painting’s composition. By looking above, the pair seeks to pull the viewer’s eye upwards, to the Virgin and Child at the heart of the image.

“They are absolutely unusual,” admits Andreas Henning. “Usually, angels would be playing music, singing, laughing and playing with the Christ Child. But there’s no painting in the world, to my knowledge, where they appear to wait in such a bored manner.”

Perched on the ledge of an altar, the angels were intended to wait not only for the monks of San Sisto to celebrate mass, but for the Madonna to carry the Christ Child to Earth.

Yet emptied of its religious meaning, the cherubs’ pensive appearance makes for an effective marketing tool. “It is so interesting for all the marketing experts to interpret the two angels however they want,” says Andreas Henning. “They can be waiting for a glass of prosecco, or tasting chocolate.”

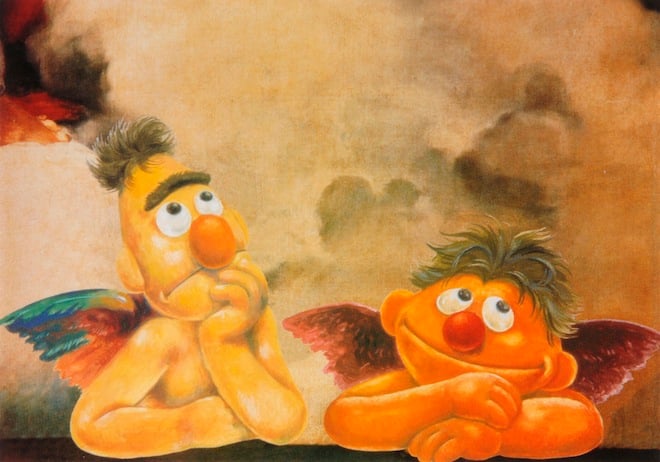

In the 1970s, the cherubs were transformed into the advertising darlings they are today. The pair found its way onto neckties, snow globes, Tupperware, toilet paper and air freshener. They could just as easily promote the divine pleasure of cabernet sauvignon or tiramisu, as take on the appearance of Bert and Ernie.

“They’ve been totally transformed and are now plastered everywhere… even here!” says a visitor from Spain, Nati Guil Grund, 31, referring to a box of “Erotic bread” mix on display.

In fact, the angels have become so dissociated with the painting itself, in the public mind, that the Dresden Gallery purposely sought to reunite both in promoting the exhibit. It concentrated on images of the Madonna herself, and chose the slogan: “The fairest woman in the world turns 500.” Bernhard Maaz compares the disconnect to that of the two famous hands reaching out to one another in the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling fresco, The Creation of Adam. “Everybody knows these two hands,” he says. “But not everyone knows to whom they belong.”

Besides the exhibit’s amusing section dedicated to the cherubs, a room on the 20th century shows how the Sistine Madonna inspired Dadaist collages and even Hindu lithographs from India. In the winter of 1943, the painting – along with Rembrandts and Van Dycks – was hidden in a railroad tunnel outside of Dresden to protect it from bomb attacks. At war’s end, the Soviet “Trophy Commission” moved more than 1,200 works from Dresden’s Gallery to Kiev and Moscow, and the Sistine Madonna vanished from the public eye for 10 years. The Soviet Union finally returned the painting after the Warsaw Pact of 1955, and through films and paintings later propagandized its “rescue” from Nazi Germany.

The Sistine Madonna has been given a new, baroque style frame for the exhibit. The “birthday present,” handcrafted and gilded, shows Raphael’s work in a new light. “I never liked the painting,” confesses Marion Schilling, 58, from Hamburg. “When I was a kid, a print of it hung in a friend’s bedroom and I remember finding it horribly kitsch. I wanted to be reintroduced to it. And I have a better appreciation of it now, now that I see it in its whole context.”

The Dresden exhibit has been visited by 56,000 visitors in its first three weeks alone. They crowd around the Sistine Madonna, some discussing details of the painting with friends. Some step back to get a better look, and step forward again. Others imitate the angels’ poses. Perhaps a few even relate to the words of German author Thomas Mann: “My greatest experience, as far as paintings go, continues to be the Sistine Madonna in Dresden.”