A fascination with Mary, Queen of Scots

She married thrice, tried to kill the queen and we can’t get enough of her

Reign — ââ¬ÅSnakes in the Gardenââ¬Â — Image Number: RE102a_0218.jpg â⬔ Pictured: Adelaide Kane as Mary, Queen of Scots — Photo: Ben Mark Holzberg/The CW — © 2013 The CW Network, LLC. All rights reserved.

Share

Mary, Queen of Scots has been dead for 426 years. Yet, surprisingly for a woman most famous for the method of her execution—a beheading so botched it took three swings of the axe to complete the job—she is being resurrected as the heroine of a new teen drama on the CW network. Filled with hunky men and gorgeous women, Reign—a one-hour show focused on the monarch’s early years in France—is getting a lot of buzz as the network’s first costume drama. Period pieces are not traditionally staples of teen TV viewing, but Mary was a perfect subject, as co-creator and executive producer Laurie McCarthy explains. For one thing, she travelled at all times with a posse of Scottish girls, known as the Four Marys. Then she had “terrible taste in men,” McCarthy notes. And her life was so tumultuous, “you can create a love story within it.”

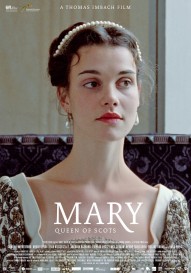

Reign, which starts Oct. 16 on the M3 channel in Canada, is only the latest in a series of new works centred on Mary that are flooding airwaves, theatres and galleries. An eponymous film, by Swiss director Thomas Imbach, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, focuses on her political and personal life in Scotland, as does an exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland. At Ontario’s Stratford Festival, Mary Stuart, a play about her captivity and relationship with Elizabeth I—the cousin she plotted to assassinate—ends its run Oct. 19; it’s been extended four times. Two other movies are in various stages of completion, and the opera Mary Stuarda hits London’s Royal Opera House next year.

In some ways the different adaptations seem to be about different people: there’s the scheming, passionate queen who’s the subject of Imbach’s film, the tragic prisoner in Cimolino’s play—shut away at age 24, Mary spent 19 years in confinement before being executed—and of course, the teenager of the TV series, adapting to royal life in France, her fiancé’s home, where she was pitted against a mother-in-law to beat all mother-in-laws, Catherine de’ Medici. Remarkably, this was all one life—and all true.

Mary had three husbands, two of whom died precipitously, was queen of two countries, Scotland and France, and desperately craved to be monarch of a third: England. (Hence that assassination plot.) She was as famous for her vivacious wit and intelligence as for her imperious height of five feet, 11 inches. “She was tall, strikingly beautiful, she could speak so many languages,” says Antoni Cimolino, Stratford’s artistic director. “Even her faults have a kind of romance about them.”

“With Mary there is intrigue, love, sex, conspiracy, bad doings, murder, happiness and sadness,” says David Forsyth, a senior curator at the National Museum of Scotland, where the acclaimed Mary exhibition is drawing record crowds. Since major events of the sovereign’s life are still shrouded in mystery and intrigue, “there are very polar positions that one can take on Mary that make it an alive, interesting story,” he explains. “She was a much-maligned monarch or she was a scheming, murdering adulteress.”

In Reign, Mary is a 15-year-old, freed from a convent (a bit of artistic licence on the part of the producers) to the freedom of life with the French royal family. A queen in her own right—she inherited the Scottish throne when six days old—she’s set to marry Francis, the royal heir. Yet in typical teen fashion, the path of love isn’t smooth. Mary is attracted to his half-brother, Sebastian, son of the king’s mistress. Meanwhile, Francis’s mother, Catherine de’ Medici (played by Canadian Megan Follows) plots against her after the famous prognosticator Nostradamus warns, “She will cost Francis his life.”

There has been an avalanche of criticism over the show’s historical inaccuracies—Mary had lived in the French court since she was five, Francis was a sickly prince unsuitable for television, and Sebastian didn’t exist. McCarthy isn’t concerned. “We’re wedging stories in between the pages of history,” she says. So in Reign, the Four Marys are all slim with long tresses—think Kate Middleton before a blowout—wearing tight strapless gowns that wouldn’t look out of place on a Hollywood red carpet.

Certainly the historical record provides plenty of drama too. Mary became queen consort of France at 16 after her father-in-law was fatally injured in a jousting match. Before her 18th birthday, she was a widow, and with Catherine now running France for Francis’s 10-year-old brother, Charles IX—she had little choice but to return to a land she hadn’t seen since she was a child. She only ruled Scotland for seven years—1561 to 1567.

In that time, she fell for her cousin Lord Darnley and wed him even before the pope sanctioned the marriage. Darnley was “vain, foolish, idle, and violent, with a rare talent for offending people, including his wife,” writes historian Julian Goodare. Less than a year after their nuptials, he stormed the queen’s quarters and helped stab David Riccio, her Italian secretary, 56 times. Three months later she gave birth to a son, James. A few months later, Darnley’s body was discovered near a destroyed house. He had been strangled or suffocated.

In Imbach’s film, and by many historical accounts, Mary approves of the murder, likely undertaken by James Hepburn, earl of Bothwell, whom she quickly takes as her third husband. Certainly revulsion at the killing and her remarriage echoed throughout Scotland, and as mobs yelled, “Burn the whore! Burn the murderess!” she was forced to abdicate. Her 13-month-old son, James, was now king. In 1568 she fled to England.

For all this, Mary is in some ways a very modern figure—which may explain the flurry of interest. “Her job was to produce an heir, but she insisted on having her own life and love,” Imbach notes in an interview, rather than being “a queen encased in her obligations.” Unlike her unmarried cousin the Virgin Queen, who sacrified happiness for duty and country, Mary led a free-spirited, chaotic life. And her fortitude is impressive. On her return to Scotland, the Catholic monarch found a nation dominated by Protestants, with feuding lords and clan leaders unhappy at the idea of sharing power with a teenaged queen. To Forsyth, she was a revelation. “I discovered a quite able political queen who had a sense of realpolitik. And when she led her troops into battle, she was at the front with the breastplate and a metal helmet.”

By the time she was 24, Mary had lost all power. Elizabeth and her advisers would keep her locked away until her death. Since she was closest in line to the English throne, the Scottish queen, and her ambitions, were a threat. Mary would “have couriers call out to her when she passed, ‘Make way for the queen of England,’ ” says Peter Ackroyd, author of Tudors, a new history of the dynasty—this while Elizabeth was on the throne. “Elizabeth could never ignore or forget. It was one of the guiding forces of her reign: to keep Mary, Queen of Scots at arm’s length.”

The modern reinterpretations are only continuing a process that began 426 years ago—Mary’s cultural and historical re-evaluation began almost immediately after her death. On Feb. 8, 1587, dressed in red, the colour of martyrs, Mary, Queen of Scots was executed by her Protestant cousin, after being convicted of plotting against her. She was 44. In a letter written on the eve of her death, she declared, “The Catholic faith and the assertion of my God-given right to the English crown are the two issues on which I am condemned.” Mary was transformed from meddling foreigner to Catholic legend.

Sixteen years later, her Protestant son would inherit Elizabeth’s throne as King James I, unite England and Scotland and set about rehabilitating his mother. In 1612, he had his mother’s body moved to a prominent spot in Westminster Abbey, overshadowing the crypts of her Tudor enemies and relations, including Elizabeth. In death, Scotland’s most famous woman had finally outmanouevred her rivals. Mary, Queen of Scots believed in destiny. While in prison she had embroidered a motto that would prophetically sum up her legacy: “In my End is my Beginning.”