Trending: Why psilocybin could be used in mental health treatment

Psilocybin, better known as the stuff that makes mushrooms magic, is the next big wellness industry—and a new frontier for mental health

(Photo courtesy of iStock)

Share

If you hadn’t noticed psilocybin’s move toward the mainstream, a company like Numinus will come as a surprise. Led by founder and CEO Payton Nyquvest, Numinus is a brand-fantasy of the next iteration of wellness: clean, straightforward, empathetic, inclusive and self-aware. It’s one of several Canadian companies—Field Trip Health and Wellness among them—ready to capitalize on psilocybin. Its head office in Vancouver’s Gastown may look like any random vegan café, but instead of cookies, it has ketamine—currently the main psychedelic legally used in therapy in Canada. At some point the company plans to use psilocybin too. Found in “magic mushrooms,” psilocybin is in clinical trials, in Canada and internationally, for use as a potential treatment for mental illness.

Nyquvest turned to psychedelics to treat his long-term chronic pain, and his healing experience contributed to a significant career change. A smart, aggressive operator, Nyquvest transitioned from a director position at Mackie Research Capital to founding Numinus in 2018—the same year cannabis was legalized in Canada.

Why psilocybin? Caroline MacCallum, who is the medical director of the Greenleaf Medical Clinic and a clinical assistant and adjunct professor at UBC, explains that structurally, psilocybin is like serotonin. “This can lead to an antidepressant or an anti-anxiety effect,” MacCallum says. The medical community has heard that some patients have experienced visual distortions like hallucinations, powerful emotional experiences or self-reflective insights, all of which MacCallum says can lead to new ways of thinking.

Numinus and other Canadian health companies are considering psilocybin for the treatment of addiction, depression, anxiety, PTSD and, perhaps most notably, end-of-life distress via intentionally pursued trips on the drug. A landmark 2006 Johns Hopkins study found that psilocybin might “occasion mystical-type experiences,” and NYU Langone published findings in August of 2022 that saw a significant reduction in alcohol dependence when subjects combined psilocybin and psychotherapy. Following these studies, among others, psilocybin has emerged in the medical community as an exciting potential treatment. But it remains illegal in this country outside of clinical trials and exceptions via Health Canada’s Special Access Program—which provides drugs with clinical promise to treat serious or life-threatening conditions—and through certain exemptions under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, in place since 2020.

Psilocybin research is necessarily slow and expensive. Spencer Hawkswell, who is a lobbyist and the CEO of non-profit group TheraPsil (which advocates for psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy), is working in support of a lawsuit against the government of Canada and the current federal minister of health to allow patients access to psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy; Hawkswell projects that it could be legal and regulated in a little over a year.

This moment in psilocybin is one of duality. At the same time as it’s being studied for therapeutic use, it’s also an established wellness trend, one of many that have moved from marginalized communities or a global majority culture to the mainstream West via curious outsiders, then influential figures and their followers, then reformed skeptics. Psilocybin has replaced weed as the respectable person’s low-key, illicit-ish drug of choice, in the form of microdose capsules, chocolate, or the magic mushroom as crudité. Celebrities talk openly about using psilocybin; “microdosing moms” have become their own subculture. The hesitant nerd’s guide to psychedelics, Michael Pollan’s 2018 book How to Change Your Mind, has inspired a Netflix docuseries.

MORE: How science is bringing psychedelic mushrooms out of the shadows

Unlike the research, perception seems to be progressing quickly. Through recent history, the narrative of psychedelics more generally has been on a wild ride of its own, from psychologist and psychedelic figurehead Timothy Leary’s outré-Harvard 1960s to the Hopkins study and Canadians’ changing attitudes. A 2021 poll done by TheraPsil and marketing research company YouGov found that 54 per cent of respondents, without having any additional information, supported changing psilocybin regulations for medical use. That number rose to 66 per cent when respondents were informed about research findings and current exemptions available. (Perception in the straight-arrow, stigma-avoidant business world is harder to shift, but perhaps this is being addressed by CEOs like Nyquvest and Doug Drysdale, a pharma veteran who heads the Toronto-based psychedelics company Cybin.)

This particular moment, mostly pre-regulation and post-stigma, has created an interesting scene made up of casual users, dealers, advocates, investors, executives and medical practitioners. With illegal dispensaries and home growers, this industry will continue to shift along with regulations and perceptions. If psilocybin turns out to be as effective as current research suggests, it will transcend its wellness-trend status and become a greater part of recognized health care. This is already happening in the medical community, and for people who find themselves on the edge of acceptability; all it takes is an open mind. And you know what might help with that?

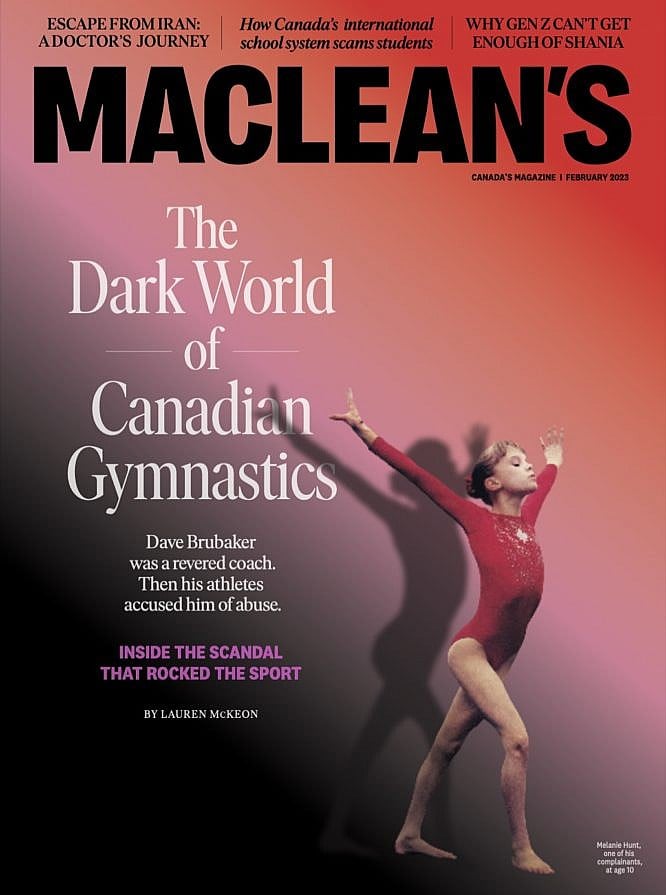

This article appears in print in the February 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.