Welcome to crazy town: The QAnon movement explained

A new book traces how QAnon’s openness to bizarre, dangerous beliefs has lent it terrifying power

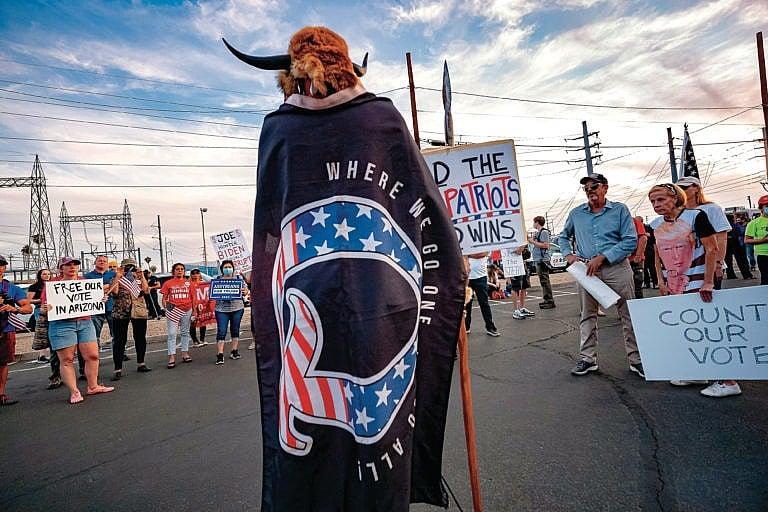

QAnon followers have lost no faith in the movement, despite its many prophetic failures (Olivier Touron/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

On Jan. 6, 2021, a mob of U.S. citizens stormed their own nation’s seat of government in an attempt to overturn Joe Biden’s victory over Donald Trump in the November 2020 presidential election. As prominent among participants as Trump flags were symbols referencing the all-encompassing conspiracy theory known as QAnon. In a fully televised event, the most immediately recognizable rioter present—bare-chested and sporting an animal-horn headdress—was Jake Angeli, a self-published author and would-be actor better known as the “QAnon shaman.” Deeply invested in the false notion the election was stolen from Trump, QAnon—an otherwise heterogenous mix of unfounded and unrelated conspiracy views—universally regards the former president as the secular Messiah destined to rescue America from a Satan-worshipping cabal of cannibalistic pedophiles centred in Biden’s Democratic party, Hollywood’s elite and the so-called deep state.

But while that may be QAnon’s primary tenet, the theories that have grown into a dangerous movement are built on previous conspiratorial tropes, some rooted in contemporary American politics and culture wars, others with far older origins. Embedded within the horrific claims that cabal members prolong their lives by harvesting adrenochrome from the living bodies of children is the ancient and ongoing anti-Semitic belief that Jews drink the blood of Christian children. (Some believers assert the existence of a video of Hillary Clinton, the chief villain in the QAnon narrative, cutting off the face of a young girl to wear as a mask while she consumes the child: a sight so gruesome, so the story goes, that the New York police who discovered the video committed suicide.)

The movement is open to virtually any such idea, old or new—so long as it completely contradicts “elite” (that is, expert) opinion—from the claim that many of the cabal have already been secretly captured and replaced by clones (President Biden, for one) to the belief John F. Kennedy Jr. is still alive. Neither of those concepts came directly from Q, the still anonymous imageboard user who began it all on Oct. 28, 2017. That their proponents are nonetheless welcome aboard the QAnon train, even those who hold that the younger JFK, who died in a 1999 plane crash, is not merely still alive but also Q himself, is crucial to its success. It’s perhaps the key factor in making QAnon exactly what Los Angeles-based conspiracy reporter Mike Rothschild calls it in the subtitle of his new book, The Storm is Upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult, And Conspiracy Theory of Everything.

Rothschild’s deep dive into the origins and evolution of QAnon identifies other supportive strands in its DNA. As important as the wide-open welcome is the participatory nature it displayed from the start. The first of Q’s postings, known as “drops,” featured the kind of reader-enticing questions and suggestions that became a hallmark of his (her? their?) messaging. Drop 1 was itself reactive, a response to another anonymous poster’s statement that Hillary Clinton would soon be arrested. Q agreed and amplified the claim. Her passport had been flagged, he wrote, “in case of cross-border run,” and the National Guard mobilized to restore order should protest riots ensue: “Proof check: Locate a NG member and ask if activated for duty 10/30 across most major cities.” Q, who went nameless for his first 33 drops, identified himself in Drop 34 as “Q clearance patriot,” a reference to the high security clearance level he claimed to possess as a government official; a day later, a Canadian user on the same site decided to call him QAnon, the name that stuck.

The remainder of Q’s 4,953 drops, just as inaccurate as the first, came at a raggedly uneven pace up to Dec. 8, 2020—sometimes 15 to 20 a day, separated by weeks of silence; sometimes just images of the U.S. flag or links to YouTube videos; sometimes hundreds of words of cryptic declarations and rhetorical questions. Consider Drop 2559, which reads in part:

“RUSSIA = THE REAL CONSPIRACY; Define ‘PROJECTION’; What happens when they lose control and the TRUTH is exposed? What happens when PEOPLE no longer believe or listen to the FAKE NEWS CONTROLLED MEDIA, CONTROLLED HOLLYWOOD, CONTROLLED BLUE CHECKMARK TWIT SHILLS, ETC ETC???”

As Rothschild notes in an interview, right-wing Internet personalities were immediately attracted to the way Q’s pro-Trump message was seemingly expressed in logic puzzles, “treating the drops as holy writ with hidden information that needed to be teased out in their own tweets or YouTube videos.” Such movement “gurus” as the Praying Medic and Joe M are as important as Q in the world he spawned, amassing social media followers and, often, lucrative pages on the Patreon paid subscription service. There is opportunity in QAnon, says Rothschild, for “grifters to make money from books and Q merch.” Another practical pillar of the movement can be found in its online trolls, he adds, some involved because “they hate Jews or Democrats,” others simply for entertainment.

READ: Bats, tats and buffalo horns: Trump’s would-be insurgents storm the Capitol

Given how outlandish mainstream belief can be in the Q universe, the influence of trolls is impossible to measure. But they may have been at work recently on June 9, when video was broadcast of a cicada from Brood X, the swarm of insects that has recently emerged from 17 years underground in Mid-Atlantic American states, landing on Joe Biden’s neck. The image lit up a 225,000-member QAnon chat group on the social media platform Telegram, because any news referencing the number 17 (the letter Q’s place in the alphabet) or the word underground (QAnon somehow believes that the deep state keeps captive children in subterranean tunnels), has the potential to be “comms” (communication) from Q. It is a very broad church indeed that can accommodate the concepts that its devil eats living children and its prophet speaks via cicada-comms.

Trolls and grifters aside, Rothschild has no doubt most QAnon adherents are passionate believers who continue, in the face of prophetic failure, to “trust the plan”—one of the movement’s signature phrases—because they desperately want its promises of coming retribution to be true. “They hate the Clintons,” explains Rothschild, before pausing to be more precise: “Well, they don’t like Bill, but they hate Hillary. Irrational, pathological hatred of Hillary Clinton has done more to power American conspiracy theory doctrine than anything else.” Tightly bound together, Rothschild says, QAnon’s constituent parts have endowed it with “an ability to survive usually seen only in cockroaches.”

Certainly the January violence and the mob’s abject failure to accomplish its goal had little effect on the popularity of either Trump or QAnon. Post-riot polls show that more than half of Republicans continue to believe the election was stolen and half of those respondents agreed with the following statement in a February American Enterprise Institute poll: “Donald Trump has been secretly fighting a group of child sex traffickers that include prominent Democrats and Hollywood elites.” The Capitol riot did mark the apogee (at least so far) of QAnon’s prominence, thrusting it into public awareness in a way earlier killings, domestic terrorism incidents, child-kidnapping schemes, and an attempt to destroy a coronavirus hospital ship—all planned or carried out in its name—did not.

But it scarcely impacted QAnon loyalty, no more than has its long list of failed predictions. As Rothschild puts it, the entire basis of QAnon has been “repeatedly disconfirmed.” And it doesn’t matter: “disconfirmation only encourages deeper belief.” QAnon found even more life during the COVID pandemic when it attracted anti-vaxxers and mask resisters around the world. “Other countries took the bits of Q that worked the best for their own political culture,” Rothschild says, especially in other English-speaking countries like Canada, where QAnon support is “very much wrapped up with anti-vax stuff and save the children movements.”

QAnon is in “a very strange sort of place now,” Rothschild says, where trust in “the plan” is liable to become ever harder to maintain. That is the same worry the FBI expressed in a newly released report: if QAnon adherents conclude that Trump is not going to be restored to office and the military is not going to swoop down upon the child-killers, then some will decide to take that task upon themselves. “No, things are not getting better,” concludes Rothschild. QAnon is “a cultish movement that’s not quite a cult, a movement with prophetic and game-playing elements, and there can be no certainty about how it will evolve in the future.”