What not to give Drake

Emma Teitel explains why it’s time for the rapper who has everything to let go

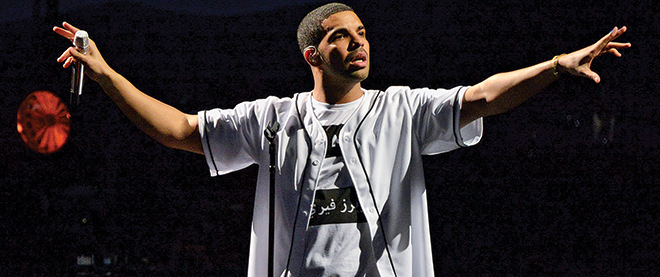

Carlos Osorio/Getty Images

Share

The protagonist in Henry James’s novel The Portrait of a Lady is a sheltered, well-to-do woman named Isabel Archer who doesn’t know what it means to suffer, but has a hunch that suffering—if also exceedingly uncomfortable and, in some cases, lethal—is interesting. James writes: “It appeared to Isabel that the unpleasant had been even too absent from her knowledge, for she had gathered from her acquaintance with literature that it was often a source of interest and even instruction.”

Isabel’s struggle—wanting what she should be glad she doesn’t have—is eternal. It’s the reason college grads move to Mozambique, or Manhattan. It’s the spirit behind the Internet meme “White girl problems” (“Will I ever get out of bed?”) and it’s the reason Aubrey Drake Graham, a.k.a. Drake, is obsessed with the hard-knock life he never had.

On Dec. 6, the Toronto rapper will perform alongside rumoured girlfriend Rihanna at the Grammy nominations concert in L.A. (broadcast live on City) and over the holidays, he’ll release five highly anticipated songs. He is at the top of his game—with almost 200 industry award nominations and 45 wins—but it seems the only distinction he’s yet to receive is the one he craves the most: “street cred.”

It’s well known that Drake was raised in Toronto’s Forest Hill neighbourhood, the Jewish-Canadian equivalent of Orange County. In high school, he didn’t sling crack; he played a paraplegic with a heart of gold on Degrassi. He’s had his hardships: divorced parents, a dad who did time in prison. But his life has been a far cry from Compton. As entertainment editor Shamika Sanders put it recently on the black-culture website Hello Beautiful, “Gangsters don’t have bar mitzvahs.”

Drake isn’t ashamed of his background (he even staged a fake bar mitzvah in one of his videos). He alludes to his middle-class Toronto roots in both his music and in interviews. But criticisms from tougher rappers have obviously affected him. “I feel sometimes that people don’t have enough information about my beginnings and therefore they make up a life story for me that isn’t consistent with actual events,” he wrote in a blog post before releasing his contentiously titled hit, Started from the Bottom, in February. “My family all struggled and worked extremely hard to make all this happen. I did not buy my way into this spot.”

The new video for his song Worst Behaviour, featuring his musician dad, Dennis Graham, was shot in a not-so-glamorous part of Memphis, the city Graham has lived in for most of Drake’s life. Isabel Archer’s “well-meaning father kept suffering at bay.” In a modern, hip-hop turn, Drake wants us to know his father exposed him directly to it. In a recent interview with XXL magazine, Graham explained, “People was saying on the streets that he didn’t have any street credit. He just wanted to show where he actually came from. We used to drive from Toronto to Memphis every summer. We lived in a section of Memphis called White Haven, and that’s where he spent his summers. And it is the hood.” Take that, O.G.s. Drake may have wintered in the Canadian burbs, but he summered in a real American ghetto.

Some fans think it’s time the rapper retired his tough-guy longings. “I wish he would stop talking about how he ‘started from the bottom,’ ” says Sanders. “There’s no fun in being poor.” She’d know: she grew up—year round—in a rough neighbourhood. She sees why Drake craves validation, having risen to fame with Lil Wayne and the Young Money crew. But she thinks street cred is passé. “It’s not so important in the grand scheme of hip hop anymore,” she says.

Sanders is right. Kanye West, whose mom was a university professor, is one of the biggest names in rap. As for rappers who did grow up in the ghetto, Jay Z just launched a luxury goods line at Barney’s in New York, where a black teen was recently arrested because security found it hard to believe he could have legally obtained the designer belt he purchased.

Drake doesn’t spend all his time brooding about his ordinary beginnings, but he should spend no time at all on it. He’s too good to worry about being bad. And as Isabel Archer learns the hard way, suffering isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.