An autopsy on the death of the Bombardier dream

How the company’s ambitions for global domination fell apart, as told through five decades of annual reports

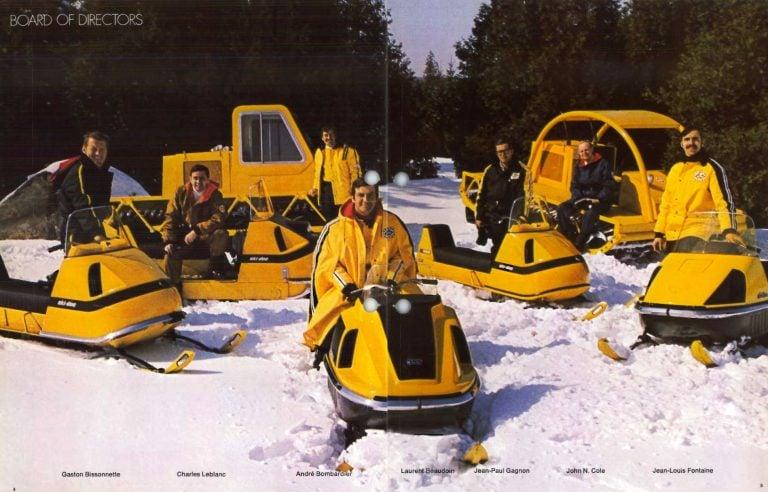

Layout from the 1969 Bombardier annual report showing the board of directors, including Laurent Beaudoin, centre.

Share

Update: On March 11 Bombardier fired its CEO of the past five years, Alain Bellemare, and replaced him with former Bombardier executive and current Hydro-Quebec CEO Eric Martel.

When Bombardier launched its first Ski-Doo snowmobile in 1959, it was initially targeted at trappers, prospectors and anyone else isolated by snow and ice. But the bright-yellow machines soon became a hot toy for affluent sports enthusiasts across North America and Europe, and by the time the company went public on the Toronto Stock Exchange a decade later, Ski-Doo sales were exploding. Bombardier’s revenues in 1970 came in at nearly $1 billion, when measured in today’s dollars, up a whopping 60 per cent in just one year.

So you can forgive Bombardier’s president, Laurent Beaudoin, for his swagger in the company’s first annual report that year. Bombardier “has proved itself to be one of the most important industrial and commercial organizations in Canada,” he crowed, while the report said the snowmobile industry was “riding the crest of the leisure market [and] the wave shows no sign of cresting . . . All forecasts point to a positive and continuing upsweep of the trend well into the 21st century.”

Instead, within three years Bombardier was in serious trouble, caught out by the 1970s oil crisis and a glut of snowmobiles on the market from more than 100 rival companies, which caused its revenues to plunge.

It would not be the last time Beaudoin miscalculated the market or allowed his optimism to blind the company to impending turmoil in the decades to come. But that early moment in Bombardier’s eventual rise to global industrial giant seems suddenly relevant again, now that the company has decided to cast off its vast commercial plane and train divisions to focus exclusively on the much smaller business of building and selling private jets to the ultimate leisure and luxury class—corporate executives and other super-rich elites.

In recent weeks, much of the focus around Bombardier’s humbling retreat has centred on the company’s ill-fated gamble to develop a new type of commercial passenger plane, formerly known as the C-Series, and how delays and cost overruns left Bombardier’s finances in tatters. Yet a full autopsy of what went wrong with the Bombardier dream has to look further than that, to the design flaws inherent in the company’s structure almost from its beginning, the company’s dependence on government largesse, and the iron grip with which Beaudoin and the rest of the Bombardier clan maintained control over the company through multiple-voting shares—control that allowed Bombardier to pursue bold, long-term bets but also shielded executives and the board of directors from the repercussions of overseeing one of the worst displays of wealth destruction in Canadian history.

Reading Bombardier’s 50 years of annual reports, in particular the letters to shareholders from Beaudoin, his son Pierre Beaudoin, and the three non-family members who have held the top job at the company, reveals how these problems built over time, and provides a window not just into how Bombardier viewed itself—and wanted to be viewed by shareholders—but also how quickly world events could upend their thinking.

It bears repeating that the Great Shrinking of Bombardier is nothing short of epic. At one point the Bombardier empire, which began with inventor Joseph-Armand Bombardier’s seven-passenger snowmobiles in 1937, spanned the globe, employing 85,000 people on six continents.

Through decades of acquisitions it grew to become the world’s fourth-largest manufacturer of rail equipment and the third-largest producer of commercial aircraft. Along the way, the conglomerate found itself in a mishmash of businesses, like operating the Belfast City Airport in Ireland, supplying missile systems to the United Kingdom and mortgaging mobile homes in Texas.

But over the past two years, and accelerating in recent months, Bombardier has been on a dizzying selling spree as it tries to tackle the crippling US$9.3 billion in long-term debt it amassed, a debt load that threatened to pull the company under completely. Last year, the company paid US$732 million in interest at a time when it reported a net loss of US$1.6 billion on revenue of US$15.7 billion. Meanwhile, Bombardier also faced a pension deficit of $1.97 billion in 2019, up from US$1.92 billion the year before.

Like a surgeon hoping to save a patient suffering extreme frostbite, Bombardier CEO Alain Bellemare amputated the company’s two largest limbs last month by offloading Bombardier’s remaining stake in the C-Series aircraft (now called the A220) to Europe’s Airbus for US$591 million, followed by an agreement to sell Bombardier’s entire rail business to France’s Alstom SA, with the company expected to receive around US$4.5 billion.

For even Bombardier’s long-time critics, the stunning comedown is disappointing. “I actually find it sad,” says Anthony Scilipoti, the head of Veritas Investment Research who has consistently warned investors away from the company since 2001. “When you look at Canada, how many global champions do we have that sell stuff around the world like Bombardier? Not many, and now Bombardier is a fragment of its former self.”

***

For a company that has more or less been in constant turnaround mode since the September 11 terrorist attacks nearly two decades ago, Bombardier’s first real moment of soul searching came in 1973. “It is now evident that the era of great expansion [of the snowmobile industry] has passed,” Beaudoin, the son-in-law of company founder Joseph-Armand Bombardier, admitted to shareholders that year. The wave, it turned out, had crested.

By then Beaudoin had decided Ski-Doos and industrial snow machines alone wouldn’t cut it, and he told shareholders the company had embarked on a “drive toward diversification.” The snowmobile may have been Bombardier’s first product, but this was the moment when the modern Bombardier, at least the one that existed until earlier this year, was born.

Some diversification efforts kept the company within its comfort zone, like the launch of Can-Am motorcycles—roughly 60 per cent of the parts of its motocross bikes could be supplied by Bombardier’s existing snowmobile operations. But Bombardier had also made a foray into the tram business with an acquisition in Austria, and it soon added to that with the purchase of Montreal Locomotive Works, at the time the third-largest manufacturer of diesel-electric locomotives in the western world.

Given all the trouble Bombardier has had in recent years delivering functioning streetcars and subway cars on time in places like Toronto and New York—just this past January, that city’s comptroller complained Bombardier “sold us lemons” because of glitchy doors on its latest subway car order—it’s somehow fitting that the company flubbed its first mass transit contract to build 423 cars for the city of Montreal. Blaming a strike by employees in 1976, Beaudoin acknowledged “considerable delay in the delivery of finished cars to the customer.” Even so, more and bigger orders soon followed, including a deal in 1982 to supply 825 subway cars to New York for $1 billion, which Beaudoin boasted was the largest single export contract in Canadian history.

Two trends were already emerging that would be central to Bombardier’s rise and eventual struggles. One was Beaudoin’s belief in the certainty of his diversification strategy. “The diversification of Bombardier is now complete,” he told shareholders in 1982, crediting the company’s mix of recreational vehicles, locomotives and mass transit for carrying Bombardier profitably through the double-dip recession of the early 1980s. Should one division find itself laid low by changes in the economy, the others could carry the day, he liked to remind shareholders each year. After the 9/11 attacks shook the airline industry and Bombardier’s share price went into free fall, he gamely tried to reassure investors that the company’s multi-decade diversification strategy protected it “against temporary weaknesses in any given sectorial or geographic market.”

The second trend was Bombardier’s heavy reliance on taxpayer support. Government made its first appearance in the company’s annual reports as a line item in 1972—“Government grants: $370,932”—but much bigger sums soon followed. Quebec offered subsidies to help Bombardier buy the Montreal locomotive business. And when it came time to land that first New York subway contract, Ottawa was there with export finance support. In thanking federal officials in his 1983 shareholder letter, Beaudoin went out of his way to argue the taxpayer support had spinoff benefits for the overall economy, like jobs, investment and regional development. In other words, what was good for Bombardier was good for Quebec and Canada.

And federal and provincial politicians at the time were more than eager to keep buying into the symbiotic relationship Beaudoin was selling.

***

While Bombardier continued to build its train and transit business in the 1980s through acquisitions in Europe and the U.S., by 1986 it was clear Beaudoin was itching for another round of diversification. The company was “aggressively exploring . . . new activities,” Beaudoin told shareholders. It was no secret those activities focused on the aerospace sector. The Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney had vowed to privatize a number of state-owned businesses, and Bombardier had its eye on Canadair, a regional jet manufacturer Ottawa had bought from U.S.-based General Dynamics a decade earlier.

In the end Bombardier won, paying $120.8 million—a bargain, considering Ottawa had sunk $2.2 billion into developing the company. (Years later, of course, a desperate Bombardier would sell its own regional C-Series to Airbus for a fraction of the US$7 billion the company spent developing the jet.) When the Mulroney government then chose Bombardier over Winnipeg-based Bristol Aerospace for a lucrative contract to service its fleet of CF-18 fighter jets ,even though the latter’s bid was lower, the outrage in the West helped spawn the formation of the Reform Party.

Incidentally, aircraft and rail weren’t the only diversification plays Bombardier was considering. At the same time that the Steve Martin and John Candy film Planes, Trains and Automobiles was in theatres in 1987, Bombardier was mulling its own entrance into the automotive sector with a project code-named Venus. Beaudoin addressed the “considerable curiosity” around its talks with Japan’s Daihatsu to launch a made-in-Quebec three-cylinder car, but said the company wouldn’t go ahead with the project unless it could be sure it wouldn’t “jeopardize the financial stability” of Bombardier. (After pocketing the equivalent of $30 million from Ottawa and the provincial government to explore the idea, it was abandoned.)

If Bombardier had decided to plunge itself headlong into the auto sector and take on the likes of Ford and General Motors—which would likely have ended as disastrously as Bombardier’s later decision to muscle into Boeing and Airbus’s territory with the C-Series aircraft—investors would have had little choice but to either sell their shares or go along for the ride. In 1981 the company had adopted a dual-class share structure, which gave Class A shares (those held by the Beaudoin-Bombardier family) 10 votes each, while the Class B shares held by the public got one vote each. As a result, for years the family controlled roughly two-thirds of the votes while holding just one-third of the equity, meaning they had complete say over naming executives, appointing board members and setting the company’s strategic direction.

“The upside of a family-controlled business is they can take big long-term bets, even if they might take several years to pay off, and with Bombardier that was the case for decades,” says Karl Moore, a professor at McGill University’s Desautels Faculty of Management. “The problem is that when they get it wrong, a family-controlled business may refuse to come to terms with reality, even if Bay Street, Wall Street, the banks and their consultants are all screaming at them.”

For the time being that didn’t matter, because in the 1990s Bombardier shares were at the start of a phenomenal bull run that would make it one of the most valuable companies in the country. The investor enthusiasm centred on Bombardier’s continuing expansion into the aerospace sector—more often than not courtesy of plum deals with governments.

***

In the U.K., the government of Margaret Thatcher embarked on its own privatization campaign, and Bombardier snapped up Northern Ireland’s Shorts Brothers aerospace company in 1989 for $60 million, with the government agreeing to inject another $550 million into the business. (Through Shorts, Bombardier would later build short-range air defence missiles for the U.K. government.) Back in Canada, it nabbed de Havilland Canada and its turboprop Dash 8 aircraft from Boeing in another windfall deal, which saw Bombardier pay $51 million for just over half the company, while the Ontario government acquired the rest (and later sold that stake to the company). Ottawa and the province also agreed to sink another $570 million into the company. In between those transactions, Bombardier made the rare deal that didn’t involve government money with its acquisition of private jet maker Learjet.

By the time it wrapped up its decade-long shopping spree, Bombardier had become the seventh-largest civil airframe manufacturer in the world, and with the rollout of new aircraft like the CRJ regional jet program and the Global Express business jets, aerospace accounted for more than half the company’s $8.5 billion in revenue by 1998. What’s more, three-quarters of its profits flowed from the aircraft sector.

However, as Beaudoin, then 61, handed the CEO reins in early 1999 to Robert Brown—an executive with the company since the late 1980s—as part of “a smooth and orderly succession in an environment of such accelerated growth” that saw him remain executive chairman—there was another part of Bombardier’s diversification strategy that had gained worrying prominence within the company, and was emblematic of the upheaval about to strike Bombardier.

***

If Bombardier could build planes, trains and snowmobiles, could it also be a bank?

For most of the 1990s, Bombardier Capital, the company’s financial arm, had mostly provided financing to its recreational products dealers to help them sell Ski-Doos, Sea-Doos and motocross bikes. But by 1998, the company was aiming much higher. In their joint letter to shareholders, Beaudoin and Brown listed the growing range of financing services they envisioned for the company: “Mortgage financing for manufactured housing, consumer loans for products purchased from dealers whose inventories we already finance, lease financing of freight rail cars, as well as computer and telecommunications equipment financing.”

It was, in short, the GE-ification of Bombardier. In the late 1990s the giant U.S. conglomerate General Electric had found apparent success by lending out money through its GE Capital subsidiary. For Bombardier’s aerospace business, that meant lending money to customers to buy its jets. By the start of 2001, the company had extended nearly $9 billion in loans and leases to customers, half of which were tied to aircraft, and taken on billions in related long-term debt. It seemed like an ideal way to drive sales, so long as aircraft prices were stable and customers could pay back their loans. In other words, so long as times were good.

Meanwhile that spring, Bombardier’s transportation division catapulted to the top position in the industry after it bought Germany’s Adtranz rail company from DaimlerChrysler for $1.1 billion, in what Beaudoin and Brown proudly noted was “the single largest acquisition in Bombardier’s history.” (The company later sued DaimlerChrysler in a dispute over the value of the rail assets it bought, and secured a $300-million reduction in the price tag.)

It would be Bombardier’s high point, in more ways than one. In early 2001, the company’s stock market value stood at nearly $34 billion, making it the only manufacturer among Canada’s 10 most valuable public companies. Since 1995, Bombardier’s stock price had soared roughly 1,000 per cent.

Then 9/11 happened. The U.S. economy tumbled into recession, private jet orders dried up and several major airlines declared bankruptcy. Thousands of layoffs followed and Bombardier Capital took a special charge of $663 million as it shuttered its retail lending business, which was more than the division had earned in profits in the previous 10 years combined. (It later sold its airline loans and leases to GE.)

As for Bombardier’s share price, it would never recover. It fell into penny stock territory in 2016 and trades today for just over a dollar a share, half of what a share in the company was worth in 1995.

Beaudoin was in a reflective mood when he sat down to pen his 2003 executive chairman’s letter to shareholders. “Last year’s difficulties remind me of the hard blow dealt the snowmobile industry by the energy crisis of 1973-74,” he wrote. “We had no other choice but to reinvent the company.” Now Bombardier was reinventing itself once again under its new CEO, Paul Tellier, and as part of the former CN Rail boss’s plan for “the new Bombardier,” the oldest part of Bombardier—its snowmobile and recreational business—had to go. “You will appreciate the difficulty facing the board and the founder’s family as they agreed to this decision,” Beaudoin wrote.

Bombardier’s investors need not feel bad for Beaudoin. The Bombardier clan was part of the private group that acquired the division, since rebranded and spun off as a public company called BRP under the ticker symbol DOO. Not only did the family seem to get a remarkably good deal, BRP would later pay a special “redistribution of capital” to the buyers that allowed them to recoup most of their investment. Bombardier’s long-suffering investors have not been so lucky—since BRP went public in 2013, its share price has risen 163 per cent while Bombardier stock is down 73 per cent. BRP’s market cap, the value of its outstanding shares, stood at $5.7 billion in late February, double that of Bombardier’s.

The longer Bombardier’s share price slumped, however, the louder calls got for the company to scrap its dual-class share structure that benefited the Beaudoin-Bombardier family over other shareholders. Tellier attempted to do away with the multiple-voting shares but was overruled by the family. As Beaudoin had stated to shareholders a couple of years earlier, the way he saw it, Bombardier’s share structure “protects all investors. Bombardier is controlled by its founder’s family, which seeks superior returns over the long term.”

In the end, Beaudoin did away with Tellier, who left Bombardier just 13 months into his turnaround plan. “We must be true to the values that have inspired Bombardier throughout its extraordinary history. Encouraging entrepreneurial spirit,” Beaudoin, the newly reinstalled CEO, wrote to shareholders in the 2005 annual report. “It was time to begin rekindling the spirit and vision that helped make this organization great.”

And what Beaudoin was convinced would Make Bombardier Great Again was a bold bet on a new jet: the C-Series.

As far back as the late 1990s, Bombardier had toyed with the idea of building a new and larger regional jet that would take it beyond the 50- to 100-seat planes it already had on offer. Before Tellier left, the company had set up a “multidisciplinary task force” to gauge the feasibility of developing a larger plane from scratch. But it’s also clear Tellier’s heart wasn’t in it. In an interview with BNN Bloomberg last December, he said he wasn’t outright opposed to the idea, but “had some hesitation . . . because I was afraid the two giants, Airbus and Boeing, would not allow Bombardier to invade the field with that size of aircraft.”

Tellier wasn’t alone. Analysts warned the company that the two aircraft companies would not abide Bombardier muscling into their airspace with the new medium-range plane, which promised quiet, fuel-efficient engines and narrow body design. Even so, with hundreds of millions in development loans in hand from Ottawa and the Quebec and U.K. governments, Bombardier gave the go-ahead to the project in 2008.

Airline analyst Richard Aboulafia still shakes his head. “It was such an unbelievably self-destructive call,” he says.

***

Pierre Beaudoin, who’d moved over from his job running the aerospace division to fill his father’s shoes as CEO in 2008, struck a confident tone in the 2011 annual report when he took part in a Q&A that accompanied his letter to shareholders. The questioner didn’t hold back. “What makes you think you can deliver on time when other larger aerospace manufacturers have failed to do so?” Beaudoin was asked. “Our confidence stems from the fact that our experience in clean-sheet aircraft exceeds that of most of our competitors,” he replied.

In reality, signs of trouble were already emerging. Orders for the new jet were slow. Then the maiden flight, set for June 2012, was delayed, then delayed again. By the time Beaudoin took part in his next annual report Q&A in 2014, he was on the defensive. “What do you say to investors who may be anxious to see new programs enter into service and start generating revenue?” he was asked. “What we do is complex,” he answered. “It takes time to design and build a new plane.” (That year Laurent Beaudoin retired as chairman. He would retire from the board of directors completely in 2018.) In fact, by then Bombardier was in full-blown crisis mode. Costs to develop the C-Series had blown past the original $2-billion estimate to more than $6.8 billion. Another aircraft under development, the Learjet 85, had to be scrapped because of the weak market for small business jets in the wake of the Great Recession. Meanwhile, complaints were pouring in to the rail division as deliveries of new trains, like 59 high-speed double-decker passenger trains for Switzerland, fell far behind schedule. All the while Bombardier’s debt load crept higher.

A fundamental flaw had become glaringly apparent—Bombardier was spread too thin between two completely unrelated sectors. Was Bombardier a train maker that also built planes, or a plane manufacturer with a side business in rail? “The question became, what synergies did planes and trains have?” says McGill’s Moore. In other words, Bombardier’s diversification strategy, which was supposed to ensure either the train or plane division would do well if the other ever got in trouble, ended up leaving the company incapable of doing either job well.

***

When Alain Bellemare arrived on the job to replace Pierre Beaudoin in 2015, he too sounded confident about what needed to be done to fix the company. “The path ahead is crystal clear,” he wrote, laying out a five-year plan to turn the company around. And as usual with Bombardier, that journey took the company straight through government coffers. After Quebec ponied up $1 billion for a 49.5 per cent stake in the C-Series project, the Trudeau government came through with $372.5 million in federal loans. Within two years Bombardier effectively conceded defeat with its ambitious jet program, and handed a controlling stake in the aircraft to Airbus, which renamed it the A220, in return for $1.

In the two years since, Bellemare has undone nearly 40 years of Bombardier deal-making in rapid succession. Consider this timeline of asset sales:

- May 2018: Sold its 370-acre Downsview manufacturing site in Toronto to the Public Sector Pension Investment Board

- November 2018: Sold de Havilland and its Q400 turboprop aircraft to a subsidiary of Longview Capital

- November 2018: Sold its flight training business to CAE

- June 2019: Sold its CRJ aircraft program to Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries

- October 2019: Sold its aerostructures business to Spirit AeroSystems

- February 2020: Sold its remaining stake in the A220 to Airbus

- February 2020: Sold its Bombardier Transportation rail division to Alstom

Bellemare has tried to position Bombardier’s cuts as part of his five-year turnaround plan. “It is a transformational deal for Bombardier [that] marks the end of our turnaround and the beginning of a new and bright chapter for the company,” he said last month on a conference call with analysts after announcing the sale of Bombardier’s A220 stake. Analysts, however, aren’t convinced. “I’m actually just very confused as to what the strategy of the company is,” Noah Poponak, an analyst with Goldman Sachs, told Bellemare. “It’s starting to look more like an asset liquidation than a turnaround. Has this always been the plan?”

The reality is, Bombardier’s future as a standalone private jet company is as murky as ever. The sale of its rail division to Alstom still requires approval from competition regulators in Europe, though Alstom CEO Henri Poupart-Lafarge doesn’t anticipate problems.

The bigger question is how Bombardier will fare when the next economic downturn eventually strikes. In past recessions, sales of lower-end business jets have taken a hit, while the market for ultra-luxury jets has held firm. “With the lower end, you’re selling to a wealthy man who owns a chain of muffler shops throughout the Midwest but has to take out a loan to buy their jet,” says the analyst Aboulafia. At the top end, where jets sell for $26 million or more, the target market is Arab heads of state, rock stars and the largest companies in the world—“people who tend to buy their jets out of the company balance sheet or with a Samsonite full of cash.” It’s this latter market where Bombardier excels. “They are mostly at the top end of the market, which is a lot more downturn resistant,” he says. “Somehow Alain Bellemare found a way, even through the worst years of the C-Series, to invest for the future in private jets.”

That’s good news for Bombardier, and perhaps even better news for taxpayers, since it will likely be a political non-starter for any government to hand money to a company so it can sell luxury jets to 0.01 per centers.

As for Laurent Beaudoin, now 81, it’s not yet clear what he makes of the new Bombardier. With just one business line, the company has more or less returned to its Ski-Doo roots—if the strategy works, it would be a repudiation of nearly half a century of Bombardier’s corporate vision.

Finally, maybe, some good news for Bombardier shareholders.