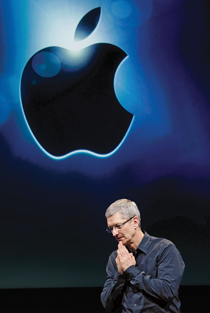

Tim Cook: Apple’s most humble servant

The new CEO, Tim Cook, is a lifelong number two, and a relentless boss

Share

Tim Cook took the stage, but not the spotlight. In his public debut as Apple chief at the unveiling of the updated iPhone on Oct. 4–the day before Steve Jobs died—the 50-year-old seemed comfortable enough, dressed in jeans, a button-down shirt and his trademark Nike runners (he also sits on the sportswear giant’s board). He even cracked a couple of jokes in his measured Alabama drawl. “This is my first product launch since being named CEO,” he said, the threat of a smile crossing his face. “I’m sure you didn’t know that.”

But it was the things that Cook didn’t do that garnered the most notice. There were no stirring Jobs-ian speeches about future-altering technology. The “ta-dah” introductions of the new phone, a social network, and a greeting card application were all left to other Apple executives. And the CEO’s sales pitch—such as it was—was all about the brand, rather than the vision. “I’m so incredibly proud of this company,” Cook told the assembled journalists. “I consider it the privilege of a lifetime to have worked here for 14 years and I am very excited about this new role.” The message was clear. Apple’s cult of personality begins and ends with its founder.

And all indications suggest that is just the way the new boss likes it. A lifelong number two—he even finished second in his class at high school—Cook has always preferred to stay in the background. He almost never gives interviews, or speaks in public settings. (The exception being his beloved alma mater Auburn University, where he gave the commencement address in 2010.) He was raised in Robertsdale, a small farming town near Alabama’s Gulf Coast, whose only other “celebrity” son appears to be Obie Trotter, a college basketball star now playing in Szolnok, Hungary. The middle of three boys born to a shipyard worker and a homemaker, Cook played in the marching band and was voted “most studious” by his peers. He went on to take engineering at Auburn, where professors remember him as “very quiet, very reserved.” After graduating in 1982, he took a job at IBM in North Carolina, distinguishing himself as the guy who volunteered to work over the Christmas holidays so that the company could fill its orders by year-end. In 1994, he joined the computer-reselling division of an electronics wholesaler, rising to COO before jumping to Compaq in 1997. Six months later, an executive recruiting firm came knocking on Apple’s behalf.

At the time, the Mac maker was in desperate straits, losing more than $1 billion a year. But Jobs, recently returned to the top job after more than a decade in exile from the company, somehow convinced Cook that better times were ahead. Against all advice, he signed on to Apple and set about remaking its operations, closing factories, slicing inventory, and travelling around the globe to renegotiate deals with suppliers. Within a year, the company was turning a profit. “For the most important decisions in your life, trust your intuition,” Cook told his Auburn audience last year. “Then work with everything you have to prove it right.”

Those who have toiled for Cook describe him as a relentless boss, routinely sending 4 a.m. emails, convening regular Sunday night conference calls and chairing meetings that drag on to all hours. And while not a screamer like Jobs, he can be withering in his own way, embarrassing underlings in meetings by asking questions they can’t answer, or presenting toilet plungers to underperformers at sales meetings. “A rare combination of extreme humility and insatiable motivation,” is how one Silicon Valley analyst recently described him to Bloomberg news.

A fitness buff, Cook survives on little sleep and a diet that mostly consists of energy bars. He rents a modest home in Palo Alto, Calif., close to Apple headquarters, and his few vacations are usually spent hiking or cycling. A fan of Bob Dylan and an admirer of Robert Kennedy, his abiding passion is AU Tigers football. And according to Out magazine’s annual list, he is the most powerful gay man in America. Last year, he earned US$59.1 million in salary, bonuses and stock options.

When Jobs’s health problems first came to public knowledge in 2004, Cook told friends that the Apple head was “irreplaceable.” Over the ensuing years, he has been forced to re-evaluate that opinion. In his message to staff this week, Cook mourned the loss of a “visionary and creative genius,” as well as an “inspiring mentor,” promising to continue building the company in Jobs’s spirit. To date, it’s the only statement he’s made. Tim Cook likes to stay in the background. And for the foreseeable future, Apple’s products are going to have to speak for themselves.